Let us first be reminded that this ongoing study, now running for about ten months, has made a solidly supported case for Herod's death taking place just after Nisan 1 in the spring, two weeks before Passover, in 4 BC. We will not rehash that evidence here; see the ABR website for those articles. Its significance for this particular study is that it restricts all possible dates for the birth of Christ to the years before 4 BC. And more narrowly yet, when the implications of the slaughter of the Bethlehem innocents two years old and under are accounted for, it points to the birth of Jesus taking place around 6 BC. Thus, the date of Herod’s death sets the stage for the workable options.

The Census of Quirinius

Since Luke 2:2 tells us that Mary and Joseph were forced to go to Bethlehem for a census at the time Jesus was born, knowing when that happened would be very helpful. However, determining when it took place is a complex matter defying an easy solution. My understanding has been influenced by the recent work of Daryn Graham (The Reformed Theological Review 73:3 [December, 2014], “Dating the Birth of Jesus Christ,” online at https://www.academia.edu/attachments/56722230/download_file?st=MTU0NDU0MjAwNyw3NS44OC45NC4xMjYsMTI4OTg2MDU%3D&s=profile). He builds upon a number of earlier scholarly proposals, all of which aim to reconcile Luke 2:2 with the known historical reality that a controversial census took place in 6 AD, when Quirinius was governor of Syria. The studies taken into account by Graham’s work include, amongst others, those of John H. Rhodes (“Josephus Misdated the Census of Quirinius,” JETS 54.1 [March 2011], 69–82); John M. Rist (“Luke 2:2: Making Sense of the Date of Jesus’ Birth,” JTS 56.2 [2005], 489–491); and William M. Ramsay (The Bearing of Recent Discovery on the Trustworthiness of the New Testament [London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1915], 292–300, online at https://biblehub.com/library/ramsay/was_christ_born_in_bethlehem/chapter_11_quirinius_the_governor.htm). Jack Finegan also addressed the matter in his Handbook of Biblical Chronology, rev. ed., §519–526.

Of critical importance is that Tertullian had written in Adversus Marcion, 4.19.10, that Jesus was born when Saturninus was governor of Syria (9–6 BC per Finegan, Handbook, rev. ed., §519, which reflects his earlier—and we believe correct—opinion that Herod died in 4 BC): “Also it is well known that a census had just been taken in Judaea by Sentius Saturninus, and they might have inquired of his ancestry in those records.” Graham observes (cited footnotes and comments added in brackets):

This census began, according to the Roman historian, Cassius Dio [54.35], in 11 BC, when Augustus alone [on his own initiative] decreed that he and the Roman Senate were to register themselves. Then, as an extension of this decree, in 8 BC, Augustus, once again alone—just as Luke’s Gospel testifies regarding its census [Luke 2:1, "a decree went out from Caesar Augustus"]—went an extra step and decreed that all Roman citizens be registered. As Augustus’ own epitaph-cum-autobiography, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti [8], states:

With consular imperium I conducted a lustrum (census) alone when Gaius Censorinus and Gaius Asinius were consuls [i.e. 8 BC], in which lustrum were counted 4,233,000 heads of Roman citizens.

The fact that the 11 BC and this 8 BC happened to be closely related is made clear by the fact that in his Res Gestae, there is no mention made by the emperor of any other census that he decreed alone. They were the one enterprise.

Unlike the later 6 AD census, which was performed for taxation purposes (and resulted in civil unrest in Judea, so it was long remembered), this first census—or better, registration—headed up by Quirinius at Augustus’ behest, was performed to obtain head counts and, according to some scholars, administer oaths of loyalty to the emperor. Finegan (Handbook, rev. ed., §524) agrees that “there could have been other kinds of Roman ‘enrollment’ which were not subject to taxation.” It appears to have been implemented uneventfully, save for the inconvenience of forcing people to travel to their ancestral towns.

Since Luke’s precise expression in 2:2 says this first census took place while Quirinius was “governing” Syria—the word is the participle of hegemon, essentially meaning “leader,” and describes his actions rather than ascribing the title of “governor” to him—the likelihood is that at this time Quirinius was serving as Augustus’ authoritative personal representative in Syria, rather than as governor of the province. There were two distinct positions of authority in Syria at this time, the imperial representative—a procurator, such as Pontius Pilate was (Finegan, Handbook, rev. ed., §522, who cites Justin Martyr, Apology 1.34)—and the governor proper. Quirinius held both positions at different times.

A great deal more could be said, but for now I simply want to draw the reader’s attention to the time period which keeps coming up in relation to the first census headed by Quirinius: the years 8–6 BC. Keeping in mind that the Magi gave Herod information that prompted him to kill all the Bethlehem boys “from two years old and under” (Mt 2:16, probably meaning between the ages of one and two), plus they visited Herod at Jerusalem rather than at his winter quarters at Jericho, this visit probably took place in the summer or early fall of 5 BC (we have to allow for their travel time to and from Persia while avoiding the hardships of a winter journey). Add between one and two years to that, and early spring in 6 BC seems to be a good fit for Quirinius’ census.

Another insight derived from Glenn Kay’s website, http://messianicfellowship.50webs.com/yeshuabirth1.html, points to the same general time:

The Roman and Judean rulers knew that taking a census in winter would have been impractical and unpopular. Generally a census would take place after the harvest season, around September or October, when it would not seriously affect the economy, the weather was good and the roads were still dry enough to allow easy travel…Luke's account of the census argues strongly against a December date for Messiah's birth. For such an agrarian society, an autumn post-harvest census was much more likely.

Although the above article is trying to marshal arguments in favor of a fall date for Christ’s birth, and for that reason focuses on the harvest season, the very same logic can be applied to a spring pre-planting census. This consideration would likewise fit with Quirinius implementing his census in the early spring of 6 BC, near the end of Saturninus’ term as governor of Syria, but before the Nisan religious festivals began and created scheduling conflicts.

God’s “Appointed Times”

When I first planned on writing this article, my best guess for when the Lord was born was around Hanukkah. My reasoning was that, despite an apparent connection with efforts by the Roman Catholic Church to co-opt the pagan celebration of the Saturnalia, December 25th not only had a long history of Church observance, it was also in very close proximity to Hanukkah, the Feast of Lights. That Jewish festival could readily be connected with the coming of the One who said, “I am the light of the world” (Jn 8:12, 9:5). It was an appealing connotation.

At the same time, the idea that Christ could have been born on the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot, also called the Feast of Booths) likewise had considerable appeal. This is a particularly popular opinion amongst Messianic Jews; see, for example, http://messianicfellowship.50webs.com/yeshuabirth1.html. The connection is made with John 1:14, which literally says in the Greek, “And the Word became flesh and tabernacled among us.” That imagery is also quite attractive to those who are partial to seeing analogies and symbolism between the life of Christ and the characteristics of Jewish holy days.

Nevertheless, it became clear that there was a fundamental difficulty in equating several such favored dates with the birth of Christ. It lay in the fact that the only possibilities where we can reasonably imagine God intended to make such connections, were with events He Himself had set up. In Leviticus 23, the Lord refers to such events as His “appointed times” (Heb. מוֹעֵד, mow`ed), and goes on to list several of them:

Shabbat—The Sabbath day (Lev. 23:3)

Pesach—Passover (Nisan 14, Lev. 23:5)

Feast of Unleavened Bread (Nisan 15–21, Lev. 23:6)

Shavuot—Feast of Weeks/Pentecost/First Fruits (one varying day in Sivan, Lev. 23:10 ff)

Rosh Hashanah—Feast of Trumpets (Tishri 1, Lev. 23:24)

Yom Kippur—Day of Atonement (Tishri 10, Lev. 23:27)

Sukkot—Feast of Booths/Tabernacles (Tishri 15–21, Lev. 23:34)

Note that Hanukkah is not on the list. This should not surprise us, since it was a man-created celebration of the rededication of the Temple by the Maccabees. There is nothing in the Scriptures to indicate God commanded Hanukkah to be memorialized due to having prophetic significance, so it is presumptuous to think He would have imbued it with a special type/antitype relationship with the life of the Messiah.

Likewise not on the Leviticus list is the first day of the Jewish religious calendar, Nisan 1, known as Rosh Chodashim, “the head of the months.” When God declared in Exodus 12:2, “This month shall be the beginning of months for you; it is to be the first month of the year to you,” He did not single out the first day of Nisan as warranting special observance as an “appointed time.” Nevertheless, God Himself chose it later as the date when the Tabernacle was first set up: “On the first day of the first month you shall set up the tabernacle of the tent of meeting” (Exodus 40:2). That passage comes to a climax at verse 34: “Then the cloud covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the LORD filled the tabernacle.” Nisan 1 was thus a truly significant date in Jewish history, the date when God first tabernacled with man.

The Pilgrimage Festivals

Deuteronomy 16:16 tells us,

Three times in a year all your males shall appear before the LORD your God in the place which He chooses, at the Feast of Unleavened Bread and at the Feast of Weeks and at the Feast of Booths, and they shall not appear before the LORD empty-handed.

These three feasts are also known, respectively, as the Passover (the Feast of Unleavened Bread, observed on the Jewish dates of Nisan 15–21), the Feast of Weeks (Shavuot, early in the month of Sivan), and the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot, Tishri 15–21). We observe in this verse that these occasions, known as the three pilgrimage festivals, were to be observed specifically in Jerusalem (“the place which He chooses”). No other place would do. Therefore, it was not possible for Jesus to be born in Bethlehem during the Feast of Tabernacles, because Joseph, as an observant Jew, would have had to be in Jerusalem that week. It is as simple as that. Proposing that the Feast of Tabernacles corresponded with the birth of Jesus for reasons rooted in typology or analogy is a non-starter, because Joseph would not have gone to Bethlehem at that time, nor would the Romans have purposely riled up the Jews by forcing them to gather for a census when one of their major festivals took place.

There is another thing to realize about the Feast of Booths. It is a fall festival, variously taking place in September or October, with symbolism tied to the Second Coming of Christ, not His First Coming; the spring festivals symbolize the latter. Moreover, the true sense of God “tabernacling” with man is fulfilled not in the imagery of a sukkah tent—a temporary dwelling used by farmers during harvesting—but in the mishkan, the tabernacle tent that covered the Holy of Holies wherein the Shekinah glory of God dwelt. And this mishkan was completed on Nisan 1 in the spring (Exodus 40:2), not on Tishri 1 in the fall. The clear implication is that we should seek a fulfillment of the imagery of Christ tabernacling with us (John 1:14) in an event taking place in the spring month of Nisan. (I am indebted to Messianic Jewish rabbi Jonathan Cahn for this insight. A friend introduced me to Cahn’s ideas in a YouTube video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptlsXtTf6n0. Some of Cahn's observations can be faulted, but the video drove me to examine for myself whether the things he claimed were true. I discovered that many do hold up to scrutiny.)

Therefore, with no need to debate the validity of their symbolic interpretations, we can immediately set aside both Hanukkah and the Feast of Tabernacles from further consideration (as well as the Feast of Unleavened Bread and Shavuot, the other two pilgrimage festivals). We turn instead to developing a chronology of Christ's birth based on several texts from Scripture and some extrabiblical sources that preserve important historical clues.

“There were Shepherds Staying Out in the Fields…”

Many have proposed the shepherds of Luke 2:8 were out in the fields at night because it was lambing season, with the implication that it was early spring. However, although in America a single spring lambing season is the norm, the same does not hold true in Israel. The flocks there stay out in the open all year round if weather permits, or are given shelter during the coldest months and driven into the fields in early spring to graze until fall.

H. Epstein, Professor Emeritus of Animal Breeding at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an unbiased expert on these matters, wrote a very informative article at http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/p8550e/P8550E01.htm about the Awassi, an outstanding breed of sheep found widely in the Near East:

Awassi ewe and lamb (H. Epstein)

Awassi ewe and lamb (H. Epstein)The Awassi is the most numerous and widespread breed of sheep in south-west Asia…The flocks of the Bedouin and of the majority of fellahin (peasant agriculturists) are kept in the open, day and night, throughout the year…However, the hardiness of the Awassi may break down during a succession of rainy days during the cold season…Stationary Awassi flocks owned by fellahin are commonly grazed in the neighbourhood of the villages…In the Syrian Arab Republic, flocks belonging to fellahin are usually taken by shepherds to mountain pastures in the spring. They return to the villages for the winter when temperatures at high altitudes are very low and the mountains are covered with snow [which could happen in the Judean hill country]…Bedouin and fellahin shepherds know nothing of tent or house but live entirely in the open together with the flocks under their care. They are working 365 days a year, from 13 to 16 hours a day. Their work includes shepherding, watching at night…In Iraq, the principal lambing season of Awassi ewes is in November, and in Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic and Israel in December-January…(emphasis and brackets added).

It is therefore erroneous to attribute the shepherds’ nighttime vigil described by Luke as due to lambing season. Another website, http://messianicfellowship.50webs.com/yeshuabirth1.html, similarly reports:

Israeli meteorologists tracked December weather patterns for many years and concluded that the climate in Israel has been essentially constant for at least the last 2,000 years. The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible states that, "broadly speaking, weather phenomena and climatic conditions as pictured in the Bible correspond with conditions as observed today" (R.B.Y. Scott, Vol. 3, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 1962, p. 625).

The temperature in the area of Bethlehem in December averages around 44 degrees Fahrenheit (7 degrees Celsius) but can drop to well below freezing, especially at night. Describing the weather there, Sara Ruhin, chief of the Israeli weather service, noted in a 1990 press release that the area has three months of frost: December with 29 F. [minus 1.6 C.]; January with 30 F. [minus 1.1 C.] and February with 32 F. [0 C.].

Snow is common for two or three days in Jerusalem and nearby Bethlehem in December and January. These were the winter months of increased precipitation in Messiah's time, when the roads became practically unusable and people stayed mostly indoors.

This is important evidence to disprove a December date for Messiah's birth. Note that, at the time of Messiah's birth, the shepherds tended their flocks in the fields at night. “Now there were in the same country shepherds living out in the fields,” wrote one Gospel writer, “keeping watch over their flock by night” (Luke 2:8). A common practice of shepherds was keeping their flocks in the field from April to October, but in the cold and rainy winter months they took their flocks back home and sheltered them (emphasis added).

The Companion Bible, Appendix 179 says:

Shepherds and their flocks would not be found “abiding” (Gr. agrauleo) in the open fields at night in December (Tebeth), for the paramount reason that there would be no pasturage at that time. It was the custom then (as now) to withdraw the flocks during the month Marchesven (Oct.–Nov.) from the open districts and house them for the winter.

This information indicates the shepherds could have been out in the fields with the sheep at night by Nisan 1, from mid-March to early April (cf. https://www.hebcal.com/holidays/rosh-chodesh-nisan), but not earlier in the winter.

“…Keeping Watch Over Their Flock by Night…”

Not only were the flocks staying outside in the open fields after the spring warm-up began, the shepherds at this time were keeping active watch over them at night. This detail also is understood by many interpreters to imply lambing season, but it need not. As mentioned above, Epstein puts the lambing season in Israel from December to January, during the time when the highland sheep would probably not have been in open pasture. The flocks’ need for protection at night goes beyond lambing season, since they would need to be guarded from predators, perhaps even from thieves if they were quartered close to town. It may be that in the providence of God, He had Luke record the detail of nighttime watching so we might know that Jesus was born after sundown. Since the Jews reckoned their days as beginning in the evening at sunset, the Messiah was born shortly after a new calendar day had begun.

The Time of the Magi’s Star*

Now we turn our thoughts to the timing of the Star of Bethlehem. Let us first refresh our minds about the natal story as given by Matthew:

Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him”…Then Herod secretly called the magi and determined from them the exact time the star appeared…and the star, which they had seen in the east, went on before them until it came and stood over the place where the Child was…And having been warned by God in a dream not to return to Herod, the magi left for their own country by another way...Then when Herod saw that he had been tricked by the magi, he became very enraged, and sent and slew all the male children who were in Bethlehem and all its vicinity, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had determined from the magi (Mt 2:1–16, abridged).

By far the most vigorously marketed theory of the Star is that put forth by Ernest L. Martin, published as The Star that Astonished the World. The Internet website version is at http://www.askelm.com/star/star001.htm. Since we have already presented a detailed critique of Martin’s 3/2 BC timetable for the birth of Christ elsewhere in The Daniel 9:24–27 Project series (see the ABR website), we consider his thesis fundamentally flawed. His 1 BC date for Herod’s death renders his birth year for Christ wrong, therefore his time for the Star must be wrong as well. Thus, we will not devote time to Martin’s ideas here.

What are the other options? Various websites have offered differing proposals for the type of astronomical phenomenon it was—a star, a planet, a conjunction of planets or stars, a comet, a meteor, and a supernova have all been suggested, as well as different years. How is one to narrow it down?

The crux of the matter was identified by Jonathan Cahn in a video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptlsXtTf6n0. It is this: How did the Magi come to identify the Star specifically with a “king” of the “Jews” (Mt 2:2)? Cahn apparently drew his information—but neglected to credit the source, at least in the video—from Michael R. Molnar, “The Magi’s Star from the Perspective of Ancient Astrological Practices” (QJRAS [1995] 36, 109–126, online at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-data_query?bibcode=1995QJRAS..36..109M&link_type=ARTICLE). The theme of Molnar’s paper is succinctly put on page 119: “The Magi’s Star had to be Jupiter drawn within Aries in an event that was dramatic from the perspective of an ancient astrologer.” In the Summary at the beginning of his paper (p. 109), he also states:

The Magi’s star is proposed to have been a pair of auspicious lunar occultations [hidings] of Jupiter that signified to ancient astrologers the birth of a king. These events occurred in the zodiacal sign of Aries that symbolized Herod’s kingdom during this era. The birth of Christ probably corresponded to the first lunar occultation on 6 BC March 20, that exhibited astrological attributes found in imperial [royal] horoscopes (emphasis and brackets added).

Molnar also discusses a second occultation several weeks later on April 17, after the Moon had passed around to the other side of the Earth, when the phenomenon changed from one taking place around dusk in the western sky, to one occurring before† dawn in the east. We will only concern ourselves with the March 20 event, because Molnar apparently did not realize that the second occultation of Jupiter in 6 BC cannot be reconciled with the one-to-two-year delay between the Magi’s sighting and their report to Herod about it. Another reason to look closely at the March 20, 6 BC occultation is its rarity: in an email to the Cambridge Conference discussion list posted at http://defendgaia.org/bobk/ccc/cc120501.html, Mark Kidger wrote:

Molnar's theory is important in that the event that he describes is genuinely very rare. I have checked all lunar occultations of Jupiter from 200BC to 1BC, some 390 in all, finding to my considerable surprise that only in 136BC and in 6BC did occultations take place in Aries.

Before continuing, we pause to note Cahn’s comment in his video: “Now we know astrology is wrong, bad, have nothing to do with it, but God is sovereign, and back then astrology and astronomy were basically the same.” By considering Molnar’s research as offering a possibly valid insight, we are not for a moment excusing what we think of as astrology today—the idea that our fate is controlled by the stars, an idea anathema to our omnipotent God. We are only recognizing the potential that God Himself, in this case, was using something, though corrupted by evil, for good. After all, God did say in Genesis that He made "the two great lights"—the Sun and Moon—and also the stars, to function as signs (Genesis 1:14–16). We have to find some way to accommodate this biblical fact in our thinking about it.

Now, Jupiter was known as the planet that, in the astrological symbolism of the Magi, signified a king, while Aries was the constellation connected with the land of Judea. Molnar states (p. 111):

The connection between Aries and Herod’s realm is discussed in the Tetrabiblos of Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria (c. AD 100–178). Astrologers had compiled lists of countries that were said to be controlled by certain zodiacal signs. According to Ptolemy, Aries ruled “Coele Syria, Palestine, Idumaea, and Judaea” which comprised Herod’s kingdom.

Hence, the Magi read in the heavens, a “king of the Jews.” And not just any king, but an exceptionally significant one due to the astrologically noteworthy occultation (a kind of conjunction) of Jupiter by the Moon as Jupiter entered the constellation Aries. Molnar observes on page 120:

On 6 BC March 20 (March 18 Gregorian Calendar) 1 min after sunset in Jerusalem the Moon occulted [had a conjunction with] Jupiter while in Aries. Mars was also present in Aries about 7½° above the Moon and Jupiter. The occultation ended half an hour later almost on the horizon. Although this significant astrological event was hidden by the bright sky, the evidence is that the astrologers had mathematical skills to indicate that there was an occultation (emphasis and brackets added).

A possible issue with Molnar’s thesis is the idea that a bright sky would have prevented the March 20 occultation from being visible. He apparently drew this conclusion with Jerusalem in mind. Since the Magi’s homeland was in Persia further to the east, however, the sun would have set earlier there, so that brightness might not have been a problem. Could this be checked?

At http://www.astro.rug.nl/~vdkruit/jea3/homepage/Bethlehem.pdf, Dr. Piet van der Kruit published a slide show (in Dutch) that looked at numerous options for the identity of the Star. Slide 76, presented as part of his discussion of Molnar’s ideas, illustrates (reproduced at right) the position of Jupiter relative to the Moon as viewed from Jerusalem. This prompted me to contact Dr. van der Kruit to ask if the conjunction would have been visible to the Magi back home in Persia as well. He kindly answered me the same day (personal communication, 12/21/18):

Central Persia (or Iran) is essentially at the same geographic latitude as Jerusalem. So, in general terms the configurations would look the same at the same local time. Also setting of the Sun, Moon, planets and other celestial objects occurs at roughly the same local time. But in Persia, being to the east, the local time is ahead of that of Jerusalem, meaning that the setting of the Sun, Moon, planets and other celestial objects occurs earlier in real time. I estimate the distance some 2000 km, which at geographical latitude 30 degrees corresponds to a difference in real time of roughly 1.3 hours. This means that the occultation happened well after the Moon and Jupiter had set in Persia and were below the horizon and invisible.

It thus appears doubtful that the Magi would have seen the actual occultation take place in real time in Persia. But by the same token, Jupiter would have been a more visible evening star to them. Matthew 2:2 has the Magi saying, “we saw his star in the east,” and this they could have done. They could have seen Jupiter entering Aries and approaching a new or very thin crescent Moon before the conjunction, with the conjunction being predicted from the known position of the Moon relative to Jupiter rather than actually being seen. It would have been the fact of the conjunction, rather than the real-time sighting of it taking place, that would have imparted extraordinary astrological significance to the event.

Now, understanding that the Magi were from Persia (where they were heirs of the divinely revealed insights of Daniel), they were looking west to see Jupiter enter Aries after dusk. Doesn’t this conflict with “we have seen his star in the east”? The solution lies in also reading Matthew 2:1, to give a little more context. That verse tells us, “magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem.” “From the east” thus refers to the homeland of the Magi which was east of Jerusalem, not the location of the star in the sky. If we apply this context-dependent understanding to 2:2, the Magi were saying: “We saw his star when we were back home in Persia east of here, and have come west to worship him.” They would have had opportunity to see this phenomenon around dusk as they looked to their west. Suggesting, as Molnar does, that the text is talking about the "heliacal rising" of Jupiter due east just before sunrise,† is to read technical astronomy into a non-astronomical text. “In the east” needs to be understood contextually as referring to the Magi’s homeland relative to Judea.

A summary of Molnar’s findings aimed at a popular audience can be found online at http://movies2.nytimes.com/library/national/science/122199sci-archaeo-jupiter.html. Also, in a February 1998 NASA Astrophysics Data System article (The Observatory, vol. 118, pp. 22-24, online at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-data_query?bibcode=1998Obs...118...22D&link_type=ARTICLE), M.M. Dworetsky and S.J. Fossey reported that they confirmed Molnar’s conclusions using Dance of the Planets and SkyMap software.

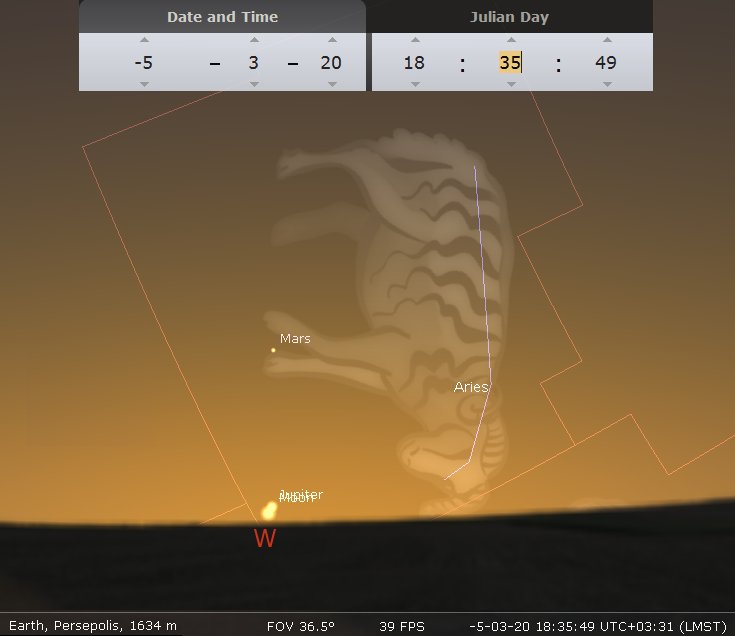

[Addendum, 12/22/18: I obtained a copy of the free astronomy program Stellarium. After getting a basic feel for it, I somewhat arbitrarily chose Persepolis, Iran, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire ruled by Cyrus, as a possible home base of the Magi. Then I set the date for dusk on March 20, 6 BC (strangely, the software includes a year 0, so the year had to be set to -5), and the view due west from Persepolis. I was able to confirm for myself that there was an occultation of Jupiter by the Moon in Aries after sunset. Here is a screen capture from Stellarium of that information. One can see Jupiter and the Moon almost meeting on the horizon.]

For the moment, we will just keep in the back of our minds this detail: Molnar says that the Star was an occultation of Jupiter by the Moon in Aries, which took place around dusk on March 20, 6 BC. Both the year and the early spring timing is consistent with the other data we have turned up.

The Significance of Abijah’s Division

The story of the events leading up to the birth of John the Baptist, as given in Luke 1, is critical to our analysis. Here is an abridged version of this passage:

In the days of Herod, king of Judea, there was a priest named Zacharias, of the division of Abijah; and he had a wife from the daughters of Aaron, and her name was Elizabeth…Now it happened that while he was performing his priestly service before God in the appointed order of his division, according to the custom of the priestly office, he was chosen by lot to enter the temple of the Lord and burn incense…And an angel of the Lord appeared to him…the angel said to him, “Do not be afraid, Zacharias, for your petition has been heard, and your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you will give him the name John”…When the days of his priestly service were ended, he went back home. After these days Elizabeth his wife became pregnant… (Luke 1:5–24, emphasis added).

Pay close attention to the fact that John’s father Zacharias served at the Temple during the division of Abjah, with the conception of John the Baptist following very soon after (though precisely how soon is not specified). When, exactly, was that time of service? There are unfortunately many analyses in the literature on how to understand the timing of Abijah’s division, with all depending on one’s prior assumptions about how the divisions served in sequence over time. We will return to discuss this in detail after a short digression to ruminate on Mary’s visit to Elizabeth.

The Travels of Mary

Luke goes on to provide information on the timing of the birth of Jesus relative to John’s conception and birth in verses 1:26–60:

Now in the sixth month [of Elizabeth’s pregnancy] the angel Gabriel was sent from God to a city in Galilee called Nazareth, to a virgin engaged to a man whose name was Joseph, of the descendants of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And coming in, he said to her…“behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall name Him Jesus…And behold, even your relative Elizabeth has also conceived a son in her old age; and she who was called barren is now [already] in her sixth month…” Now at this time Mary arose and went in a hurry to the hill country, to a city of Judah, and entered the house of Zacharias and greeted Elizabeth. When Elizabeth heard Mary's greeting, the baby leaped in her womb; and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit. And she cried out with a loud voice and said, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!”…And Mary stayed with her about three months, and then returned to her home. Now the time had come for Elizabeth to give birth, and she gave birth to a son…“he shall be called John” (brackets and emphasis added).

From Gabriel’s announcement we learn that Elizabeth had already entered her sixth month of pregnancy before the eternally pre-existent Messiah began forming His human body, “fearfully and wonderfully made” (Psalm 139:14), within the virgin’s womb. Mary’s pregnancy was later revealed by the Holy Spirit to Elizabeth, who could not possibly have known beforehand about it. This passage thus lets us know, since Mary was in her third of nine months when she left Elizabeth, that John would be born six months before Jesus. It also clarifies that Elizabeth had entered her sixth month prior to Mary’s conception, but we do not know exactly what week of that sixth month it was. It could have been any time from Elizabeth’s 23rd to 27th week. So we need to allow for a little flexibility to cover this unknown when we propose a timeline.

When did Mary go to visit Elizabeth? Insights into the likely timing may be gleaned from the impact of the normal climate cycle on her journey. First, her apparently solitary visit would not be expected to have taken place in the chill, rain and possible snow of winter, particularly in the hill country (Luke 1:39), but during the dry summer months when travel was easiest. (If we suppose Jesus' birth to have taken place around the Feast of Tabernacles, this would have placed Mary's visit to Elizabeth in the middle of the coldest and wettest part of winter, an unlikely trip for a woman traveling alone in the Judean highlands.) So we may expect Mary’s visit to have occurred sometime between late March and late October. But then, the Jewish religious calendar, with its various festivals that required attendance at Jerusalem (by the men, yes—but let's be honest, whenever possible the women would likely accompany their men), would have had a practical impact as well. They would have narrowed the travel window further, so that Mary’s trip most likely took place during the gap between the pilgrimage festival of Shavuot (late May/early June—see https://www.hebcal.com/holidays/shavuot) and the Feast of Trumpets at the start of Tishri (mid-September/early October—see https://www.hebcal.com/holidays/rosh-hashana). This would probably place Mary’s visit, and thus Jesus’ conception, during a three-month period between June and September. So, as far as Mary’s travel considerations have any bearing on it, Jesus’ conception was most probably around late May to mid-June. Since for other reasons we are working with the hypothesis that Jesus was born in 6 BC, His conception would have taken place in 7 BC. We thus propose it occurred shortly after she presumably returned with Joseph from the one-day Shavuot celebration, which was on June 7 that year. We thus place Mary’s visit to Elizabeth a week later, say June 14. Tishri 1 was on September 24 that year, so we do have a three-month window between the festivals to accommodate Mary’s visit.

There is one other detail we can draw out from this story if we read it closely. Did you notice that Mary left Elizabeth just before John’s birth? If she had arrived during Elizabeth’s sixth month and departed after staying “about three months,” John was practically a full-term baby when Mary left. Why did she not extend her visit just a little longer to see John born? Given the natural affinity of women to be involved in the birth events of close friends and relatives, her departure time seems rather awkward, to say the least. Earlier, I had supposed that she wanted to get home before winter's rains arrived, but there is a better explanation: the impending arrival of the Feast of Trumpets on Tishri 1 (Rosh Hashanah). Mary would understandably have wished to be back home with Joseph for this significant holy day. Thus, I suggest she may have departed Elizabeth's a short time before Tishri 1. That being September 24, 7 BC, we propose she left Elizabeth’s about a week earlier, say September 17. All told, her three-month visit with Elizabeth spanned June 14 through September 17, 7 BC—a visit of “about three months.”

This raises the possibility that John could have been born on Tishri 1. We know that John was born six months before Jesus. If John was born on Tishri 1—the original Jewish New Year, before God changed the calendar to instead begin with Nisan 1—Jesus could have been born on Nisan 1, Rosh Chodashim, as was suggested by Jonathan Cahn.

Hmmm…it is a tantalizing idea. It remains to be seen if other details are consistent with it. Let’s keep this suggestion in mind as this study continues to unfold. These considerations have a bearing on narrowing down the precise week when Abijah’s division served in the period of 6-8 BC. We want the selected week to be free of any conflicts with Mary’s travel requirements, and if possible, to explain her unusual departure from Elizabeth right before the birth of John.

Figuring Out the Priestly Cycles

Now we come to the area which took by far the most effort in this study. If we can pinpoint the week when the division of Abijah was serving when Zacharias had his encounter with Gabriel, we would surmount a major hurdle in figuring out when the Savior was probably born. We first need to pull together some background information.

1 Chronicles 24: The 24 Divisions of Priests

We first turn to 1 Chronicles 24:1–18. That passage presents us with the order in which the priestly divisions served in the Temple, and is really stark in its simplicity:

Now the divisions of the descendants of Aaron…they were divided by lot…

Now the first lot came out for Jehoiarib, the second for Jedaiah,

the third for Harim, the fourth for Seorim,

the fifth for Malchijah, the sixth for Mijamin,

the seventh for Hakkoz, the eighth for Abijah,

the ninth for Jeshua, the tenth for Shecaniah,

the eleventh for Eliashib, the twelfth for Jakim,

the thirteenth for Huppah, the fourteenth for Jeshebeab,

the fifteenth for Bilgah, the sixteenth for Immer,

the seventeenth for Hezir, the eighteenth for Happizzez,

the nineteenth for Pethahiah, the twentieth for Jehezkel,

the twenty-first for Jachin, the twenty-second for Gamul,

the twenty-third for Delaiah, the twenty-fourth for Maaziah.

Here we have the biblically-sanctioned service sequence for the 24 divisions of priests. Two in particular, highlighted in bold, are noteworthy. The first in the sequence was Jehoiarib, while the eighth was Abijah. We know the latter’s division was on duty when Zacharias saw Gabriel in the Temple, but we also need to know when, exactly, at least one division served in order to place Abijah’s service to a timeline. Can such an anchor point be found?

Talmud Ta’anit 29a: Finding an Anchor Point

Thankfully, God does not leave us hanging, and the answer is yes! But it is not in Scripture that we find it, but in history recorded in the Talmud, in Ta’anit 29a:

The Sages said: When the Temple was destroyed for the first time [in 587 BC], that day was the Ninth of Av; and it was the conclusion of Shabbat; and it was the year after a Sabbatical Year; and it was the week of the priestly watch of Jehoiarib; and the Levites were singing the song and standing on their platform. And what song were they singing? They were singing the verse: “And He brought upon them their own iniquity, and He will cut them off in their own evil” (Psalms 94:23). And they did not manage to recite the end of the verse: “The Lord our God will cut them off,” before gentiles came and conquered them. And likewise, the same happened when the Second Temple was destroyed (https://www.sefaria.org/Taanit.29a, emphasis and brackets added).

For completeness we point out that there seem to be conflicts between the Scriptures, Josephus and the Mishnah on how to relate the ninth and tenth of Av to the start of the Temple’s burning. This issue is discussed at length by Kenneth Doig at http://www.nowoezone.com/NTC07.htm. Briefly we will just say here that, since we take Scripture as inerrant, we go with what Jeremiah 52:12–13 states about the intentional burning of the First Temple:

Now on the tenth day of the fifth month, which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, Nebuzaradan the captain of the bodyguard, who was in the service of the king of Babylon, came to Jerusalem. He burned the house of the LORD, the king's house and all the houses of Jerusalem; even every large house he burned with fire.

This fits with Josephus’ comment in Wars 6.4.5: “as for that house [the Second Temple], God had long ago doomed it to the fire; and now that fatal day was come, according to the revolution of ages: it was the tenth day of the month Lous [Ab], upon which it was formerly burnt by the king of Babylon” (emphasis and brackets added).

Thus, Jeremiah and Josephus speak with one voice that both destructions are properly placed on Sunday, Av 10, in the week of Jehoiarib’s service. The rabbinical sages, being much closer in time to the AD 70 destruction, appear to have extrapolated the accurately-remembered start of the later destruction’s burning—an accident caused by the Roman soldiers on Av 9 as that Sabbath was coming to a close (not after it, but near its end, approaching sunset on Saturday)—to the similar event in 587 BC, which was actually done on Av 10.

Josephus: The Start and End of Each Priestly Cycle

Josephus also helps us in two other passages to understand how the Sabbath-to-Sabbath service of each priestly division was implemented:

But David…having first numbered the Levites…divided them also into courses: and when he had separated the Priests from them, he found of these Priests twenty four courses: sixteen of the house of Eleazar, and eight of that of Ithamar: and he ordained that one course should minister to God eight days, from Sabbath to Sabbath (Ant. 7.14.7 [7.365 Loeb**], emphasis added).

To this we add information from Against Apion 2:8, indicating that the service specifically began after midday of the first Sabbath in the cycle, and ended before midday of the following Sabbath:

…yet do they [the priests] officiate on certain days only. And when those days are over, other priests succeed in the performance of their sacrifices; and assemble together at midday; and receive the keys of the temple…(emphasis added).

These passages tell us that Jehoiarib’s schedule in AD 70 would have him on duty, using Julian dating, from midday Saturday, August 4 (Av 9) until midday Saturday morning, August 11 (Av 16). This week is our anchor point for evaluating the chronology of the birth of John the Baptist.

Continuous Cycles or Annually Reset?

Another question that different interpreters have handled variously has to be addressed now: how were the cycles implemented? We have two basic options. One is that, once started on some unknown Nisan 1 with Jehoiarib, the priestly cycles operated continuously. This would result in Jehoiarib being displaced from the week of Nisan 1 in future years. Others suggest the priestly cycle reset every year, with Jehoiarib always serving the week of Nisan 1. Which is right?

The 1 Chronicles 24 passage given above is so straightforward, with one name following the next without missing a beat or adding any extra information, it seemingly demands that a regular, ongoing rotation of the 24 Levitical families is meant, without any resets or interruptions to its continual linear sequence. All that matters is the sequence of names. The text does not consider important exactly when in the year a division would serve, nor does it mention how often each would serve in a single year. (We know each division served at least twice each year, but the text does not even tell us that simple fact, leaving us to deduce that we are to tack on another 24-division sequence as soon as the earlier one has completed). The absence of even such basic guidance implies there were no restrictions on the cyclical continuity of the sequences. Cycle after cycle would repeat ad infinitum as long as political realities permitted. Whether any given week was part of a standard calendar month or an intercalary addition (like a leap year, to bring the calendar back into synchrony with the equinoxes and the growing season, see below) would make no difference. If there was a week to be filled by priestly service, the next division in the sequence would answer the call.

R.T. Beckwith, in “St. Luke, the Date of Christmas and the Priestly Courses at Qumran,” RQ 9 (1977), raises a dissenting voice against this apparently straightforward understanding of the division cycles. Beckwith concludes that the priestly divisions at Qumran began anew each year, with Jehoiarib always serving on the New Year of Tishri 1. However, this suggestion clashes with a fact that we have observed repeatedly in this ongoing study, that there is abundant evidence that the Jews used Nisan 1 as their New Year after the Babylonian exile, not Tishri 1. Jack Finegan (Handbook, rev. ed., §246) observes that at the start of one six-year priestly cycle, one papyrus fragment from the Qumran caves says the family of Gamul, not Jehoiarib, began that year’s cycle on Nisan 1. This actually supports the understanding, contra Beckwith, that the priestly rotations did not reset each year with Jehoiarib covering Nisan 1. That this single reference happens to place Jehoiarib’s service on Tishri 1 can be viewed as a coincidence of that particular year, not a prescription for Tishri 1 being the change point every year. In the end, which way one comes down on Beckwith depends on the prior assumptions one brings to his work. It is inconclusive—but, after all, it is talking about the idiosyncratic Qumran sect, not the Jerusalem-centered priestly courses we are concerned with. Thus, we regard it as an unhelpful rabbit-trail we will henceforth ignore.

Therefore, each year presents 52 weekly slots to be filled by a division. With 24 slots constituting one full priestly cycle, two cycles could be completely filled each year, totaling 48 weeks. This would leave four weeks remaining, to be filled according to the 1 Chronicles 24 sequence. After the first year, whenever it was, subsequent years would start with a priest other than Jehoiarib serving during the week containing Nisan 1, as the four extra weeks in the year had their offsetting effect on the sequence of priests.

Priestly Service on the Pilgrimage Festivals

An additional question is how to relate the priestly cycle to the combined service of all 24 divisions on the three pilgrimage festivals mentioned earlier. “On the three pilgrim festivals, all the 24 mishmarot [divisions] officiated together” (https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/mishmarot-ma-amadot, cf. Mishnah Sukkah 5:7–8). The question is, were these periods of combined service interruptions to the normal sequence given in 1 Chronicles 24, or did they merely involve reinforcements joining the regularly-scheduled division to handle the unusually large crowds at those times?

It appears the latter is the case, otherwise the 1 Chronicles 24 schedule is no longer the continuous linear sequence of service times it presents itself as. We agree with Finegan (Handbook, rev. ed., §241) that maintaining this regular sequence requires viewing the extra 23 divisions at the pilgrimage festivals as reinforcements to handle the larger crowds at Jerusalem, but the week the festival lands in is still reckoned as that of the normal sequence division. Thus, a complete priestly cycle remains as Scripture puts it, a cycle of 24 weeks. After all, one of the three pilgrimage festivals, Shavuot, was only observed for a single day, not a week. We might look at the Feast of Unleavened Bread and the Feast of Tabernacles as whole-week festivals that could perhaps interrupt the order of 24 week-long divisions, but Shavuot cannot be viewed this way. It is the exception that proves the rule.

Therefore, in what follows we will place every division in its biblically-sanctioned weekly slot in a continuous, uninterrupted sequence, and on the three pilgrimage festivals view the attendance of the other divisions as supplemental manpower to help the regularly assigned division deal with the overflowing crowds.

Accounting for the Added Intercalary Months

To construct a timeline of priestly cycles extending back from Jehoiarib in AD 70 to Abijah around 6 to 8 BC, we also must account for weeks added to the Jewish calendar when it was periodically corrected with intercalary months. These were required on a regular basis to prevent the agricultural seasons from getting out of sync with the calendar over time. This involved adding the extra month of Adar II (discussed in detail at https://www.hebrew4christians.com/Holidays/Rosh_Chodesh/Adar/adar.html) according to the so-called Metonic cycle. Even though, in the biblical period, the Jews used visual sighting of the first lunar crescent to set the start of months (Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 1) rather than a calculated calendar, it is not as if they were taken by surprise by the need to add an extra month to any particular year. They would have known there were extra weeks coming up well ahead of time and would have planned for them. The 19-year Metonic cycle of intercalations had been known since the Greek astronomer Meton devised it around 432 BC, and the Jewish people were familiar with it from the time of Alexander on. We may be confident that the sages would have had the foresight to account for such added weeks in determining when the priestly divisions would serve.

In our search for the course of Abijah during which Zacharias had his angelic encounter, we will use the calendars published at http://www.cgsf.org/dbeattie/calendar/?roman=70. They have already done the hard work of applying all the needed 19-year Metonic cycle intercalations to the Jewish calendar, and then synchronized it with the corresponding Julian dates. For the period we are interested in, from the fall of the Temple in AD 70 back to 8 BC, this strategy takes into account all of the weeks the Jews added to accommodate their intercalations. All we then must do is tie the weekly 1 Chronicles 24 priestly cycles into it. (Those who wish to delve further into the intricacies of calendar calculations are encouraged to investigate the information at https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Mathematics_of_the_Jewish_Calendar/The_recurrence_period_of_the_calendar.)

A major advantage to this approach is that it eliminates the need for us to sweat the details of how, exactly, intercalation was done by the Jews. Nor is there any reason to concern ourselves with the eye-glazing intricacies of intercalations for the Qumran calendar as Beckwith did, mentioned above. Although Jack Finegan (Handbook, rev. ed., §244-249) devotes some time to presenting Qumran calendar matters, we can ignore that material for our purposes, since our key date for tracking the priestly cycles—Jehoiarib's service beginning the evening of Av 9, 70 BC—is predicated on the calendar norms used by the priests at Jerusalem. Whatever the sect at Qumran might have done with their calendar is nothing more than a matter of scholarly curiosity. In writing this I am not disparaging the prodigious, detailed work various scholars have poured into their Qumran calendar studies, only pointing out that it does not apply to the task at hand.

We also acknowledge there were interruptions in the faithful observance of the priestly cycles at times in Jewish history (as pointed out by Doig at http://www.nowoezone.com/NTC07.htm), but these do not concern us either. Only the years from Herod the Great to Titus are pertinent, and they were a period of stability for Jewish religious practice at the Temple. There are no gaps to account for when the regular progression of the priestly cycles might have been interrupted during that period.

Pinpointing When Abijah’s Division Served

Having now finished laying the groundwork, without further ado we are ready to figure out when Abijah’s division served.

Jehoiarib’s division was on duty in AD 70 from August 4–11 (Av 9 [evening]–Av 16 [morning]). This being Division 1 of 24, it means the division that had served the previous week, July 28–August 4 (Av 2 [evening]–Av 9 [morning]), was Division 24, Maaziah. We continue to follow this pattern back in time, Delaiah > Gamul > Jachin > etc., week after week, in unvarying and predictable sequence. We take into account all intercalary months, plugging the priestly divisions into every added Adar II as needed, without disturbing their regular sequence. We add 23 divisions of reinforcements on each of the three pilgrimage festivals, while keeping the weeks of those festivals locked to the division whose sequence it was. It’s pretty straightforward, once all the research was done to find explicit justification for how to handle the priestly cycles. More often than not, the various attempts of various scholars to contribute “fresh, unique insights” did nothing but confuse the issue.

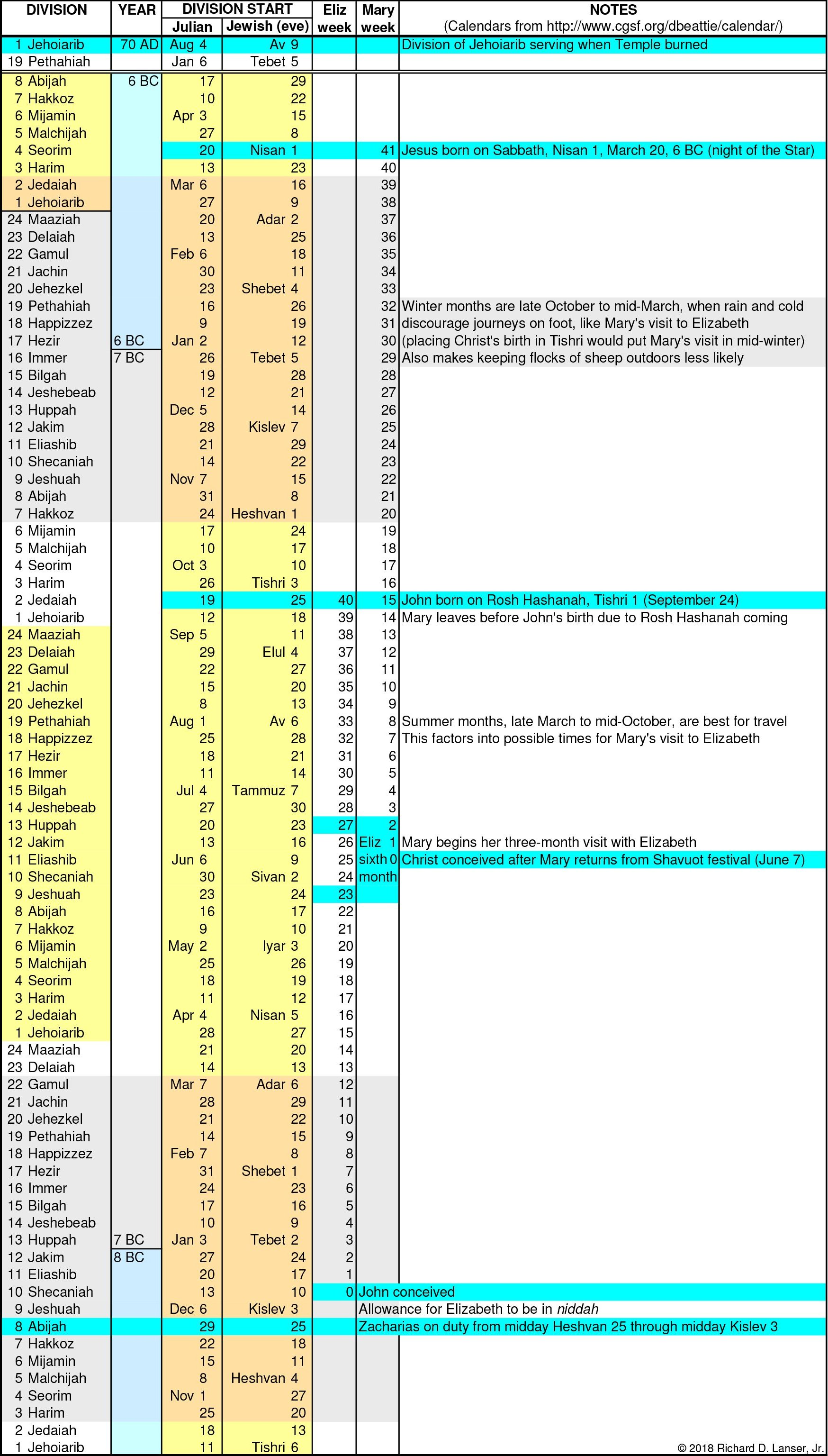

A great deal of time was spend keying into a spreadsheet the Sabbath dates (both Julian and Jewish), which were also division start dates, for every year from AD 70 down to 8 BC. The calendars at http://www.cgsf.org/dbeattie/calendar/?roman=70 were a tremendous help in accomplishing this. Then the proper division was applied to every week. Cycle numbers were also added, to more easily identify what block of 24 divisions was being referred to. If the cycle starting with Jehoiarib the week of Av 9 in AD 70 (August 4) is designated Cycle 1, then Cycle 2, again starting with Jehoiarib, would have started 24 weeks earlier on Shebet 18, AD 70 (February 17). Continuing blocks of 24 divisions back in time eventually brings us to the start of Cycle 168, where we find Jehoiarib serving the week of Tishri 6, 8 BC (October 11).

Now, since our interest is in finding a date for the division of Abijah that fits smoothly with all of the accumulated information laid out above, I flagged dates when Abijah’s division served between 8 and 6 BC. These included Heshvan 25, 8 BC (November 29); Iyar 17, 7 BC (May 16); Heshvan 8, 7 BC (October 31); Nisan 29, 6 BC (April 17); and Tishri 20, 6 BC (October 2). This gives us several candidates for Zacharias’ week of service. I then compared those candidates to other criteria looked at previously, especially the following events and the significance attached to them:

Slaughter of the innocents – over a year before fall of 5 BC, spring of 6 BC works

Quirinius census – while Saturninus was governor, early 6 BC

Mary visits Elizabeth – shortly after last spring festival, Shavuot

Mary leaves Elizabeth – just before John’s birth, due to Rosh Hashanah (Tishri 1)

Jesus born six months after John – consistent with Nisan 1

Tabernacle completed on Nisan 1 – Jesus born that date by “tabernacling” analogy

Star of Bethlehem – occultation of Jupiter in Aries on March 20, 6 BC

The shepherds in the fields – probably after mid-March in the highlands

Looking these over, we see that the spring/March/Nisan timeframe comes up repeatedly, plus there is the precise proposed Star of Bethlehem date, March 20, 6 BC. The astronomer, Molnar, nowhere says anything about Jewish dates, and seems not to have considered their significance. There’s not a whisper about Nisan, Tishri, or anything of the sort in his article. We should not be surprised at this, for after all, he is a scientist, not a theologian. But if we check that date against a Jewish calendar, what do we find? In 6 BC, March 20 landed on Nisan 1.

This is a rather stunning discovery, so our attention is immediately narrowed down to looking for a week compatible with it for Abijah’s service. If we provisionally take Nisan 1, 6 BC as the birth date of Jesus, counting back 40 weeks, a full-term pregnancy for Mary, takes us to Elizabeth’s sixth month. There is nothing in Scripture I am aware of that allows us to specify precisely when within that sixth month Mary showed up at Elizabeth’s door, so we allow for some ambiguity here. Let us be generous and say, since the sixth month of pregnancy is generally regarded as weeks 23–27, Mary’s conception could have taken place anytime during that sixth month, so we will count back an additional 27 weeks. This would bring us to the approximate date John was conceived. Then there is another unknown, the amount of time from when Zacharias’ service (Abijah’s division) began until John’s conception. The Jewish custom of niddah, ritual purity separation during menstruation, may come into the picture here as well, since Elizabeth would probably have (unexpectedly!) started menstruating again while Zacharias was away on duty. To accommodate this possibility, let us add another week.

All told, then, based on pregnancy considerations alone, we are looking at the passing of about 68 weeks between the birth of Christ and the week of Zacharias’ service. What week do we get if we suppose Jesus was born on Nisan 1, 6 BC, and go back 68 weeks? The week of Heshvan 25–Kislev 3, 8 BC (November 29–December 6), when Abijah’s division was on duty.

Let us further analyze this scenario from the perspective of Mary’s travels. We proposed that she did not leave for Elizabeth's until after the spring festival season had completed. (This would be consistent with the grace of God, for it would spare Mary the need to travel in the cold and wet of winter, which would have been the case if Jesus had been born during the Feast of Tabernacles.) After staying for three months with Elizabeth, she returned home without waiting to see John born because of the impending Feast of Trumpets, Rosh Hashanah, on Tishri 1. In 7 BC Shavuot, the pilgrimage Feast of Weeks, was on Sivan 10 (June 7), squarely in the middle of Elizabeth’s sixth month on the proposed chart that follows. So this works out just fine. And at the other end of her visit, we proposed that she left shortly before Tishri 1, just before John’s birth. In 7 BC, Rosh Hashanah just happened to take place during the 40th week of John’s conception! Yes, Mary’s travels fit this date, too. I do not think it would be a coincidence if God, thinking of type/antitype significance with His date choices, chose to have John born exactly on Tishri 1 as the forerunner for Jesus who was born on Nisan 1. This degree of precision is not provable from the records we have, though. Holding it is a matter of faith, but one I personally am comfortable with.

(The full version of this chart, with all priestly divisions given from AD 70 to 8 BC, can be seen HERE. Charts last updated 12/27/2018.)

Conclusions

In this study we have demonstrated very strong support for the idea that Jesus the Messiah was born on the Sabbath-opening evening of Nisan 1, 6 BC. It was a night when Persian astronomers could see the astrologically significant phenomenon of Jupiter, the “king” star, being occulted by the Moon as it entered Aries, the constellation signifying Judea. Nisan 1 was the date that God first tabernacled with the Israelites at Sinai, so it was a fitting day for Him to also “tabernacle” with mankind in the person of His Son. This early spring date would likewise accommodate Mary and Joseph’s travel to Bethlehem for a 6 BC census, without conflicting with required attendance at a pilgrimage festival. The weather was improving by that time, so the required journey from Nazareth was not a great hardship, and it was also possible for the shepherds to keep their flocks outside in the fields and watch over them by night. Six months earlier, John the Baptist would have been born, right after Mary had to leave Elizabeth, after going to visit her once Shavuot was out of the way. And finally, six months earlier yet, Zacharias was serving in the Temple as part of the regular service of the division of Abijah, between November 29 and December 6, 8 BC.

In the end, this researcher now feels quite satisfied that, against all expectations, it is possible to say with a great deal of assurance that we can identify when the Savior was born. The year was 6 BC, and it happened the Sabbath night of Nisan 1. The way all of the various factors fit together is a powerful indication that there is indeed an all-powerful God who involves Himself in human affairs, who loves us so much that He sent His Son into the world to die for sin on our behalf. It is also a testimony of the truth of the inspiration of Scripture. We can trust it as His very Word to men.

As far as The Daniel 9:24–27 Project is concerned, what we take away from this particular study is yet another confirmation that the timetable we have been developing is correct. Its support for a 6 BC date for the Lord’s birth reaffirms, once again, that Christ was born about two years before Herod the Great’s death in the spring of 4 BC. In turn, we can have confidence in our earlier analysis that places His Crucifixion on Passover, Nisan 14, AD 30. His baptism would have been in the fall of AD 27. We will later find this date to be of critical importance when we examine in detail the text of Daniel 9.

No comments:

Post a Comment