The crescent moon--Sin

The eight-pointed star--Ishtar

The shiny four-pointed sun--Shamash.

The two alters with horned crowns--An and Enlil,

The fish/goat --Enki

The umbilical cord and knife--Ninhursag.

The lion with wings and the pole with panther heads--Nergal, god of the underworld

The vulture and carved weapons--Zabada, the god of hand-to-hand fighting;

The grubs and curved weapon--Ninurta

The dragon--Marduk, the leader god

The triangular tool--Nabu, a son of Marduk and patron of writers

The tablet on the sitar--Sod, god of wisdom

The third god is Cula who is guarded by the sacred dog; she was the goddess of healing

The bull and altar with the forked lightning--Adad

The lamp--Nusku

The plow--Ningirsu

The bird perched on a post--Sbuqamuma

The other bird--Shimaliya

The altar with a sheaf--Nisaba, goddess of corn

The scorpion--Ishtara

The snake with horns --Ningizida, god of architects and engineers

From: http://www.crosscircle.com/sumerian_and_babylonian_gods.htm

Canaanites--the Canaanites lived in the land that we now call Israel.

El-- father of gods, mankind.

Athirat--El's consort

Kothar - and - Khasis--craftsman

Shachar & Shalim--twins

Shamu--sky god

Baal-- god of fertility, 'rider of the clouds', and god of lightning and thunder

Anath-- consort of Baal, also known as Astarte, Asherah, Athtart, Anat, and Ashtoreth; lesser god of war and the hunt

Baalat-- fertility goddess

Tanit-- lady of Carthage

Shapshu-- sun goddess

Yarikh-- moon god

Kotharat-- conception and childbirth

Athtar-- possibly a god of the desert or of artificial irrigation

Sheger-- god of cattle

Ithm-- god of sheep

Hirgab-- father of eagles

Elsh-- steward

Sha'taqat-- a healing demoness

Nikkal and Ib-- goddess of fruit

Khirkhib-- king of summer and raiding season

Dagon of Tuttul-- god of wheat, inventor of the plow

Baal - Shamen-- lord of the Assembly of the gods at Gubla

Milqart-- god of the Metropolis and of the monarchy at Tyre and Carthage

Eshmun-- god of healing

Yam-- sea and rivers

Arsh-- monstrous attendant of Yam

Atik-- calf of El, enemy of Baal

Ishat-- enemy of Baal

Zabib-- an enemy of Baal

Mot-- sterility, death, and the underworld

Horon-- chthonic deity

Resheph-- pestilence

Aklm-- like grasshoppers

Rephaim-- deities of the underworld

Molech--parents sacrificed children to Molech

From: http://ancienthistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa102197a.htm

Egyptians--the Egyptians lived in the land of Egypt

From: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/gods_gallery.shtml

Hittites--the Hittites lived in the land we now call Turkey

From http://www.medeaschariot.com/mytholog/hittite.htm

Hedammu--a snake

Illyankas--a dragon

Inaras--a goddess

Sea/Waters

Hurrian Kashku--moon goddess, the Hittites sacrificed sheep to her.

Upelluri--god who carries the world on his shoulders.

Hannahannas--goddess, uses the symbol of the bee.

Mikisarus

Imbaluris--messenger god

Kumarbis--father of all the other Hittite gods

Anu--most powerful Hittite god

Alalu--king of heaven, first of gods.

Storm/Weather god--his symbol is the bull

Seris--a bull

Aranzahas--a river god

Tella-a bull

Tasmisus--a child of the god Anu

Suwaliyattas--a god of war

Hebat--a lion, wife of the storm god

Wurusemu--sun goddess of Arrina, a goddess of battle.

Sharruma--a calf. Symbolized by a pair of human legs, a human head on a bull's body.

Takitis--in charge of the gods' meetings

Mezzullas--Daughter of the storm god and sun goddess.

Zintuhs--the granddaughter of the the Storm god and Sun goddess.

Telepinu--a god of farming.

Vikummi--a weapon against the storm god.

Sun-god of Heaven--the god of justice, sometimes the king of gods.

Tarpatassis--protects from sickness and grants a long and healthy life.

Alauwaimis--drives away evil sickness.

Romans and Greeks--the Romans lived in parts of the areas we now call Europe, Asia, and North Africa.

The Greeks lived in the country of Greece.

| Greek name | Roman name | Description | |

| Photos from http://www.archaeonia.com/ | |||

| Zeus | Jupiter | ruler of the gods |

| Poseidon | Neptune | god of the seas |

Photo from http://www.paleothea.com/Men.html Photo from http://www.paleothea.com/Men.html | Hades | Pluto | god of the dead |

| Hestia | Vesta | goddess of the home |

| Hera | Juno | wife of Zeus/Jupiter |

| Ares | Mars | god of war |

| Athena | Minerva | goddess of crafts and war |

| Apollo | Apollo | god of the sun |

| Aphrodite | Venus | goddess of love and beauty |

| Hermes | Mercury | messenger god |

| Artemis | Diana | goddess of hunters |

| Hephaestus | Vulcan | god of fire and iron |

False gods in modern times

People now don't worship the same gods as ancient people worshiped. But some people still worship other false gods. A false god is anything that a person worships and honors instead of the true Lord God.

In some remote parts of the world (places that are far away and hard to travel to), people still worship false gods and idols. But many people in modern cities and countries also worship false gods. Maybe they don't worship dolls or idols, but they give time, energy, and attention to other things before they honor and worship the true God.

Some modern people follow religions that do not worship the true Lord God.

Some modern people worship money. They feel that having a lot of money to buy expensive things is more important than obeying God's laws.

Some modern people feel lust (sexual feelings) and follow sexual feelings that are wrong. God's laws say that sexual relations are for married people only. People who follow lust and sinful feelings have sexual relations with people they are not married to. They may read books and magazines and watch movies about sexual situations. They worship their lustful feelings instead of obeying God's laws.

Some modern people worship famous people. They do what famous people tell them to do instead of doing what God says we should do.

Ajé Shaluga

Among the Yoruba people, Ajé Shaluga is the orisha of money and treasures. Ajé Shaluga can present in both male and female form to their followers. Ajé Shaluga is responsible for providing fair wages to their people for work activities and money to cover the needs of Yoruba families. Although they are a minor orisha, Aje Shaluga has a vast following as they are associated with happiness and joy, stability, prosperity, and spiritual wealth. Offer of flowers, fresh fruit, pigeons, and necklaces made of coins and shells are given to Aje Shaluga.

Babalú Ayé

Babalú Ayé is recognized among the Yoruba people of Nigeria and Benin as the ''Healer God''. Babalú Ayé helps heals humans against infections and epidemics which are sometimes caused by his spirit cousin Sakpata, who is known as the plague god. Babalú Ayé is represented as walking on crutches and completely covered to hide his diseased skin. He is also commonly seen having two dogs to help sniff out infections. Followers of Babalú Ayé offer him things like white wine and grains.

Bumba

Bumba, also known as Mbombo, is the creator god of the Kuba people in Central Africa. According to the Kuba people, Bumba vomited into the universe and produced the sun which dried up the water on Earth creating land. Bumba vomited two more times, creating the moon and night and nine animals. The nine animals produced more species to live on Earth, and eventually, humans came into creation. Bumba is represented as a giant, white-colored figure that has been ill for millions of years, which explains the use of vomit to create life on Earth.

Eshu

Eshu is commonly known among the Yoruba people of Nigeria as the trickster god who serves as a messenger between heaven and earth. Eshu is said to be a protective and benevolent spirit who needs to receive constant appeasement in order out fulfill his assigned functions. Although Eshu serves Ifa, the chief god, in some myths, Eshu often plays tricks on Ifa with one being tricking Ifa out of the secrets of divination and another telling a story of Eshu stealing a yam from the high god.

Nana Buluku

Nana Buluku is primarily found in the Fon religion but is also known among the Yoruba people. Although Nana Buluku did not have a direct role in creation, she is referred to as the supreme goddess and represents motherhood. According to Fon mythology, Nana Buluku played an important in the creation of the world as she gave birth to twins Mawu (African moon goddess) and Lisa (African sun god), who joined forces to create the world. Among the Yoruba people, Nana Buluku is regarded as the grandmother of the orishas and represents the ancestral memory of their ethnicity.

Oba

Oba is the Yoruba goddess of the river. She is believed to be the daughter of Yemaya and the first wife of Shango. According to Yoruba mythology, Oba gave Shango her ear to eat, which eventually leads to their separation. Distraught, Oba became the Oba River which intersects with the Osun River, named for another wife of Shango. Since the river flows through Iwo, the people of Iwo are often referred to as the children of the Oba River.

Obatala

Known as the sweetest god for their compassion towards humans, Obatala is considered the ''Child of God'' due to their father being the powerful Olorun. Obatala does not identify as male or female. They are described as androgynous. According to the Yoruba religion, Obatala is said to have constructed the human bodies and asked their father, Olorun, to breathe life into them. Because of their genderless identity, Obatala is a god for all and values fairness, forgiveness, and compassion. Obatala also values forgiveness and compassion as they once made a mistake and neglected their duties. Obatala was tasked with creating the world but got distracted at a party and could not fulfill their duties. Their brother, Oduduwa, created the world instead.

Oduduwa

Among the Yoruba people, Oduduwa is the creator of the Yoruba race and religion. Oduduwa's older brother, Obatala, was supposed to be the original creator but after getting drunk at a party, Obatala failed to complete his task. When Obatala was unable to create, Oduduwa stepped in as creator. Oduduwa came down to Earth to rule as a king among the Yoruba people and is considered to be an ancestral king and hero.

Ogo

Ogo, as known to the Dogon people of Mali, is the ''Chaos God''. Ogo is the son of Amma, who is the creator of the Dogon people. Ogo's purpose was to be one of the founders and overseers of life on Earth. Because of his fear of being separated from his twin sister, Ogo rebelled against his father causing himself to be muted and wander alone on the outskirts of human society. Ogo is represented as the ''pale fox''. It is said that Ogo influences the male personality, the premature separation from the womb, and children often resemble him during play.

Ogun

Known to the Yoruba people of West Africa, Ogun is the god of war and iron. After the creation of the earth and people, Ogun is said to have climbed down to earth on a spiderweb with the other gods. The other gods and Ogun noticed that humans needed to clear more land to build and expand. Having received the secret of iron, Ogun shared the secret with the other gods and humans. Ogun taught the humans how to craft tools and weapons.

Oko

Oko is the Yoruban god of agriculture who encourages the soil to produce bountiful crops. Oko is an orisha who was born of Yemaya. At the start of the rainy season, the Yoruban people partake in a festival to show their appreciation for Oko.

Olokun

Olokun is the ruler of the waters of Earth and is presented as both god and goddess depending on the religion. Among the Yoruba people, Olokun is the goddess of the waters. Olokun is often portrayed as being fierce, angry, and jealous. In the Yoruban religion, Olokun is the wife of Oduduwa. Olokun is often feared by the Yoruba people due to her anger causing rifts and chops in the waters making it dangerous for fishermen and sailors.

Baal, god worshipped in many ancient Middle Eastern communities, especially among the Canaanites, who apparently considered him a fertility deity and one of the most important gods in the pantheon. As a Semiticcommon noun baal (Hebrew baʿal) meant “owner” or “lord,” although it could be used more generally; for example, a baal of wings was a winged creature, and, in the plural, baalim of arrows indicated archers. Yet such fluidity in the use of the term baal did not prevent it from being attached to a god of distinct character. As such, Baal designated the universal god of fertility, and in that capacity his title was Prince, Lord of the Earth. He was also called the Lord of Rain and Dew, the two forms of moisture that were indispensable for fertile soil in Canaan. In Ugaritic and Hebrew, Baal’s epithet as the storm god was He Who Rides on the Clouds. In Phoenician he was called Baal Shamen, Lord of the Heavens.

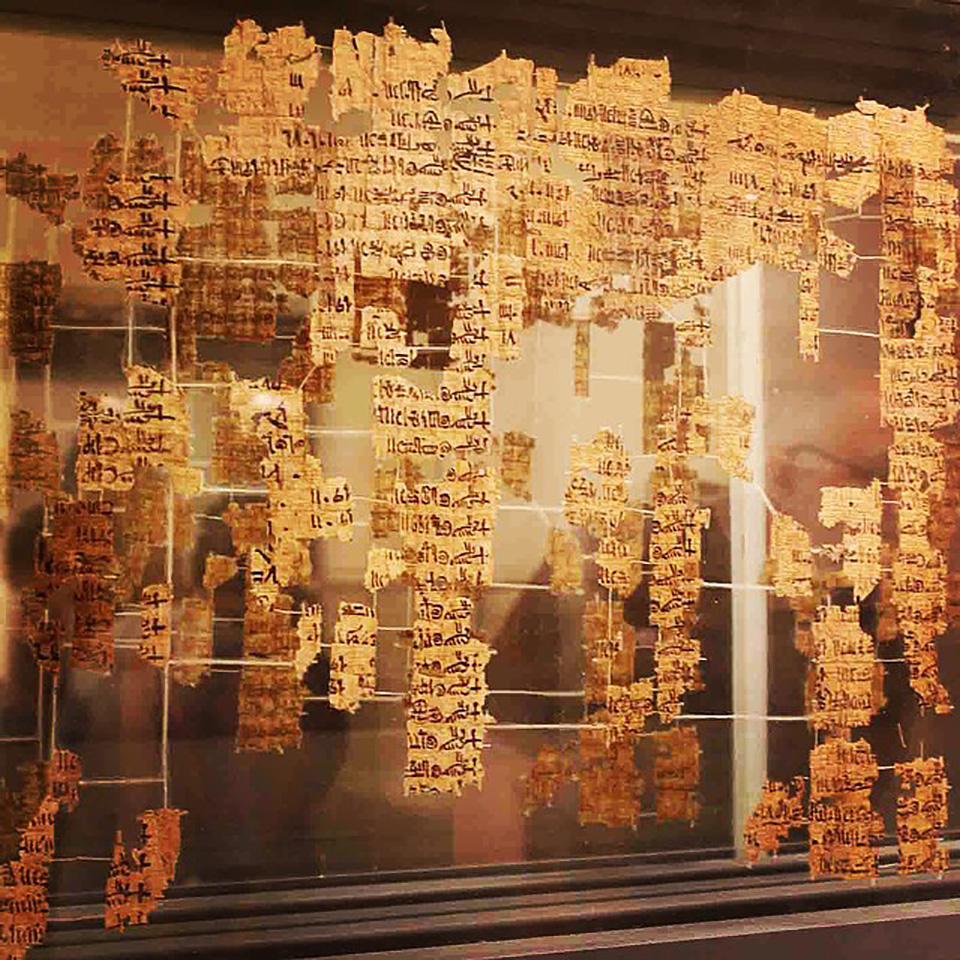

Knowledge of Baal’s personality and functions derives chiefly from a number of tablets uncovered from 1929 onward at Ugarit(modern Ras Shamra), in northern Syria, and dating to the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. The tablets, although closely attached to the worship of Baal at his local temple, probably represent Canaanite belief generally. Fertility was envisaged in terms of seven-year cycles. In the mythology of Canaan, Baal, the god of life and fertility, locked in mortal combat with Mot, the god of death and sterility. If Baal triumphed, a seven-year cycle of fertility would ensue; but, if he were vanquished by Mot, seven years of drought and famine would ensue.

Ugaritic texts tell of other fertility aspects of Baal, such as his relations with Anath, his consort and sister, and also his siring a divine bull calf from a heifer. All this was part of his fertility role, which, when fulfilled, meant an abundance of crops and fertility for animals and mankind.

The myths also tell of Baal’s struggle to obtain a palace comparable in grandeur to those of other gods. Baal persuaded Asherah to intercede with her husband El, the head of the pantheon, to authorize the construction of a palace. The god of arts and crafts, Kothar, then proceeded to build for Baal the most beautiful of palaces which spread over an area of 10,000 acres. The myth may refer in part to the construction of Baal’s own temple in the city of Ugarit. Near Baal’s temple was that of Dagon, given in the tablets as Baal’s father.

The worship of Baal was popular in Egypt from the later New Kingdom in about 1400 BCE to its end (1075 BCE). Through the influence of the Aramaeans, who borrowed the Babylonian pronunciation Bel, the god ultimately became known as the Greek Belos, identified with Zeus.

Baal was also worshipped by various communities as a local god. The Hebrew scriptures speak frequently of the Baal of a given place or refers to Baalim in the plural, suggesting the evidence of local deities, or “lords,” of various locales. It is not known to what extent the Canaanites considered those various Baalim identical, but the Baal of Ugarit does not seem to have confined his activities to one city, and doubtless other communities agreed in giving him cosmic scope.

In the formative stages of Israel’shistory, the presence of Baal names did not necessarily mean apostasy or even syncretism. The judge Gideon was also named Jerubbaal (Judges 6:32), and King Saul had a son named Ishbaal (I Chronicles 8:33). For those early Hebrews, “Baal” designated the Lord of Israel, just as “Baal” farther north designated the Lord of Lebanon or of Ugarit. What made the very name Baal anathema to the Israelites was the program of Jezebel, in the 9th century BCE, to introduce into Israel her Phoenician cult of Baal in opposition to the official worship of Yahweh (I Kings 18). By the time of the prophet Hosea (mid-8th century BCE) the antagonism to Baalism was so strong that the use of the term Baal was often replaced by the contemptuous boshet (“shame”); in compound proper names, for example, Ishbosheth replaced the earlier Ishbaal.

Semite, name given in the 19th century to a member of any people who speak one of the Semitic languages, a family of languages spoken primarily in parts of western Asia and Africa. The term therefore came to include Arabs, Akkadians, Canaanites, Hebrews, some Ethiopians (including the Amhara and the Tigrayans), and Aramaean tribes. Although Mesopotamia, the western coast of the Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Horn of Africahave all been proposed as possible sites for the prehistoric origins of Semitic-speaking populations, there remains no archaeological or scientific evidence of a common Semitic people. Because Semitic-speaking peoples do not share any traits aside from language, use of the term “Semite” to refer to the broad range of Semitic-speaking peoples has fallen out of favour.

By 2500 BCE Semitic-speaking peoples had become widely dispersed throughout western Asia. In Phoenicia they became seafarers. In Mesopotamia they blended with the civilization of Sumer. The Hebrews settled with other Semitic-speaking peoples in Palestine.

These are things that we need to know as we seek to reach Africans with the gospel of Christ.

Background to African traditional religion

African religion involves the whole of the African’s life: the environment, values, culture, self-awareness—a complete worldview. Religion considers the dynamic interaction of various activities that take place in every African community, and it permeates all phases of life. According to John S. Mbiti,

Traditional religions are not primarily for the individual, but for his community of which he is a part. Chapters of African religions are written everywhere in the life of the community and in traditional society there are no irreligious people. To be human is to belong to the whole community, and to do so [belong] involves participating in the beliefs, ceremonies, rituals, and festivals of that community.1

Still on the centrality of religion in the life of the Africans, E. Bolaji Idowu has this to say, There is a common Africanness about the total culture and religious beliefs and practices in Africa. This common factor may be due to either the fact of diffusion or to the fact that most Africans share common origins with regard to race, and customs and religious practices.2

Preview of African traditional religion

Before we launch into the important task of sharing the gospel to members of the African traditional religion, we would do well to identify this religion and know its basic tenets. African traditional religion has no sacred literature and no human founder, therefore, this religion has not been named after anyone, such as is the case in Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. A revealed religion, it came into existence through the peoples’ experiences with God from time immemorial. Passed from father to son, this religion has no zeal for membership increase, yet it is displayed everywhere for all to see. How do we identify African religion?

It should be stated that when it is said that African traditional religion has no sacred literature, it means it has no document similar to the Holy Bible of the Christians or the Koran of the Muslims.

Identification and sources of African religion

The two major ways of identifying this religion come through primary and secondary sources. The primary sources could be oral or concrete. The oral sources include myths, traditional events told as stories, as well as proverbs and wise sayings that contain the philosophy and worldviews of the people. Liturgy, worship recitals, and songs are also integral parts of this source. The concrete sources, on the other hand, include the ecological landmarks and artistic objects. The ecological landmarks refer to sacred trees, rivers, mountains, forests, and rocks. Every ecological landmark is not regarded as being sacred by Africans. But those believed to display supernatural qualities— such as protection in times of danger, or those that act as sources of supplying the needs of the people in times of scarcity—are deemed sacred. It is important to note that this worship is not directed to these landmarks but to the Supreme Being who put these objects in their strategic locations for the benefit of man.

The secondary sources are the various published works of anthropologists, social workers, scholars of religion, as well as religious leaders. Specifically, these secondary sources include books written by scholars on African religion and some have been referenced in this article. Also available are academic journals published by educational institutions, research agencies, and individuals. In addition to these are photographs and various electronic documentaries on the subject under discussion.

Fundamental beliefs of African traditional religion

P. A. Talbot wrote that African traditional religion is made up of four important elements: polytheism, anthropomorphism, ancestor worship, and animism.3 E. Geoffrey Parrinder posited that this religion should be given a fourfold classification based on belief in a Supreme God, divinities, ancestors, and charms with its accessories.4It was Ralph Tanner who maintained that African traditional religion should be seen as a threefold religion based on the Supreme Being, the ancestors, and the diviner-magician. But according to E. Bolaji Idowu,

Taking Africa as a whole, there are in reality fi ve important elements that go into the making of African traditional religion. These are belief in God, belief in divinities, belief in Spirits, belief in the ancestors, and the practice of magic and medicine, each with its own consequent, attendant cult.5

These five basic beliefs that make up the African traditional religion are corroborated by the work of Vincent Okungu, who argued that a slight difference might be observed in these component elements with different people groups in Africa to demonstrate the peoples’ understanding of God in their locality.6

These basic beliefs are:

1. Belief in God. With this belief based on God’s revelation of Himself to the Africans, God became real, and every African community has a local name for God. God has always been real and never an abstract concept to the African. The names which various African communities give to God project their best expression of Him in their religious experiences. These names are descriptive in nature because they portray the character as well as the attributes of God as understood by the people.

For instance, in the eastern part of Nigeria, God is known as either Chukwu or Chineke, which means “the big God” or “the God who creates,” respectively. The Akan people of Ghana call Him Onyame to confi rm their belief in this Supreme Being. The Mendes of Sierra Leone call Him Ngewo, which means “Creator of the universe” as well as “Father,”7while the Kikuya people of Kenya call Him Murungu, which means “Creator of all things.”8 God in the African worldview is the Controller, Protector, and Provider for the whole universe.9

2. Belief in divinities. These divinities are the functionaries, as well as ministers, in the theocratic government of the world. The divinities are there as messengers of the All-powerful God. Their power and authority are derived from the Deity in order to enable them to render acceptable services both to the Deity and to man.10

3. Belief in spirits. This concept is anthropomorphically conceived, since the spirits are both immaterial and incorporeal beings. These spirits live in rocks, mountains, rivers, trees, bushes, waterways, among other places. Another important dimension associated with this belief is the “born-to-die” idea, which is closely connected with reincarnation. This aspect of the belief claims wandering spirits specialize in finding their way into the wombs of pregnant women in order to be born and later to die. In a similar manner, it is believed in many parts of Africa that the activities of witches, who operate as mystic living creatures such as birds, bats, rats, and other living things, should not be ignored. The objectives of the witches are to inflict harm: insanity, disease, miscarriages, deformities, or any other unexplainable problem.11

4. Belief in ancestors. The ancestors are neither Deity nor divinities; they are however, the dead members of the community—known as “the livingdead”— and are believed to exist in communion with their living loved ones.12The ancestors are regarded as heads of their respective families or communities, with death as just a continuation of ancestors and their services, but now in the afterlife. Those qualifi ed to become ancestors must have lived to ripe old ages, lived godly lives, and must have had children. Indeed, where the ancestors live permanently is the “paradise” or “heaven,” which the average African longs for when he or she dies.13

5. Belief in the practice of magic and medicine. Magic and medicine could either be used in their destructive or protective forms. Protective forms are used to avert illness or calamities for the individual or communities; destructive forms are used to cause individual misfortune or communal calamities.14 The medicine man (pure herbalist) in Africa uses herbs, roots, rhizomes, and other natural materials that can be beneficial. On the other hand, the native doctor works with herbs combined with mystic powers, oracular consultations, sacrifices, and incantations. This is the most dreaded form of magic because of its secrecy shroud.

Applying Paul’s approach to adherents of African traditional religion

With this background in mind, we ask, How, then can we share the good news of Jesus Christ with the adherents of this religion?

Several methods could be applied in sharing the everlasting gospel with adherents of African traditional religion. Knowing what the Africans believe will help the Christian preacher know how and where to begin. When the apostle Paul traveled to Athens, he got the people’s attention by speaking to them on a subject already known to them, the unknown god (Acts 17: 23). Paul started where the people were, and he finally guided them to where he wanted them to be.

This method will also work well in Africa today. A sound knowledge of the basic beliefs of the people should be mastered to enable the preacher to go from the known to unknown.

Christ’s method of soul winning15

Another successful way of ministering to adherents of African traditional religion would be to apply Christ’s methods of soul winning. Ellen White outlined five unique steps that Christ applied during His earthly ministry. The first was by mingling with the people He had come to serve because He desired their good. He spent time with the people—both great and small, rich and poor, men and women, the sick and the healthy—and He made Himself available for this interaction both day and night. He did this in order to find ways to benefit the people.

Next was Christ’s humanitarian ministry. In this context Jesus Christ ministered to the people by meeting their needs. He met their needs by providing food for the hungry and healing for the sick. This ministry is needed more than ever before in Africa today, where sickness and hunger have become a daily companion to millions. How can anyone accept that Jesus Christ is the Bread of Life on an empty stomach?

Christ also demonstrated sympathy to the people. He ministered to the people in all life situations by identifying Himself with them in their times of sorrow and sickness. At Bethany, He wept because of the death of Lazarus (John 11:35). He sympathized with the people on the account of the death of His friend and because of their ignorance that He was the Resurrection and the Life. When the people were hungry and moving about as sheep without a shepherd, He had compassion on them (Matt. 9:36). By His actions He demonstrated His love and care for these people. We cannot do less for the adherents of African traditional religion today.

With all the above accomplished, Christ was able to win the people’s confidence and tell them to follow Him. Certainly some people followed Christ because of the food He provided, but the majority came to Him because He met their needs, showed sympathy to them, and worked with them as Someone who desired their good. These methods will produce the same results in soul winning when properly applied today in every African community.

Conventional methods of soul winning

The conventional methods of soul winning consist of personal and public evangelistic outreaches; mass media (radio, television, satellite); literature ministries; and educational, health, and medical institutions. These, as well as other means of sharing the good news, can also be used in ministering to adherents of African traditional religion. The second coming of Jesus Christ should be made the central theme of such soul winning. A survey from 12 African countries between 2005 and 2006 revealed that most Africans expect preachers to talk of the blessed hope.16It’s not surprising that 52.5 percent of the respondents believed that the second coming of Jesus Christ should be emphasized in every sermon. After all, the second coming of Jesus Christ will end human suffering. War, disease, and death, so common in AIDS-stricken Africa, will finally be over. No wonder so many Africans long for it!

Yes, the second coming of Jesus has become the hope for all of us, Africans included. This is the message all the adherents of African traditional religion need to hear. Using Christ’s method of soul winning, Paul’s method of sharing the good news, conventional methods, as well, in sharing the blessed hope, we will have success in this important work.

1 John S. Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (London: Heinemann, 1969), 2.

2 E. Bolaji Idowu, African Traditional Religion: A Definition (London: Scan Press, 1973), 13.

3 P. A. Talbot, The People of Southern Nigeria, Vol. 2, 1926, 12.

4 E. Geoffrey Parrinder, West African Religion (London: 1961), 12.

5 E. Bolaji Idowu, African Traditional Religion: A Definition (Ibadan: Fountain Publishers, 1991), 139.

6 File://c:Documentsand setting/all users/documents/ad.htm

7 Amponsah Kwabena, Topics in West African Traditional Religion, Vol. 1 (Accra: McGraw Feb, 1974), 20.

8 E. Bolaji Idowu, African Traditional Religion: A Definition, 152, 192.

9 Gabriel Oyedele Abe, Yawish Tradition Vis-à-vis African Culture: The Nigerian Milieu (Akure: De-Trust Honesty Publishers, 2004), 21.

10 J. N. K. Mugambi, et al., Jesus in African Christianity: Experimentation and Diversity in African Christology, 12.

11 Benjamin C. Ray, African Religions: Symbols, Rituals, and Community (NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976), 132–144.

12 Elisha O. Babalola, Traditional Religion: Islam and Christianity-Patterns of Interaction (Ile-Ife: Olajide Printing Works, 1992), 24, 25.

13 Ibid., 27.

14 Kwabena, 83.

15 Ellen G. White, The Ministry of Healing, 143.

16 Philemon O. Amanze, Preaching the Everlasting Gospel in Today’s World (Ibadan: Goldfield Publishers, 2007), 215–217.

Now, however, there is a worrying sense that certain practices are chipping away at its historic moral credibility and public strength. From an ecclesiological and theological perspective, the core of the problem lies with the rapid rise and media visibility of ‘dodgy’ (ie dubious) pastors, who are the false prophets of our day. Among the many self-proclaimed ‘men of God’ or ‘servants of God’, the values that have traditionally distinguished Christian ministry are increasingly absent:

- Values such as humility, compassion, selfless service, and servant leadership are now increasingly replaced by a preoccupation with image consciousness, self-aggrandizement, and enlargement of personal ministry influence at whatever cost.

- Previously, values such as generosity and charity, accompanied by frugal lifestyle, were self-evident markers of good church leaders, pastors, clergy, and any kinds of church workers such as evangelists or catechists. In the face of difficulty, a poor Christian could expect to get temporal help even from a materially impoverished pastor who would share the little they have. These values of previous generations of Christian workers are increasingly replaced by what seems to be an indiscriminate emphasis on material blessedness as a marker of a genuine relationship with God.

I do not know of any other ministry that has damaged the image of the church in the African public square today more than that of the self-proclaimed prophets who have perverted what charismatics believe is a genuinely biblical prophetic ministry. While this phenomenon is not peculiar to Africa, this kind of public abuse of the pastoral and prophetic ministry seems to be more obvious here than elsewhere. For this growing breed of avaricious pastors, the greater their material accoutrements, the more apparent is the stamp of God’s approval on their ministry. The Bible does warn that in the last days there will be many false prophets, and false prophets have come and gone throughout the history of church. Yet this is now too prevalent in the church in Africa.

Reasons behind it

There are many reasons for the sharp rise in self-proclaimed prophets:

- In a continent where the church is growing exponentially faster than in any other period in history, the biblical paradox of both wheat and weeds growing together is real.

- Many of these prophets are taking advantage of the numerous challenges faced by a continent that is undergoing rapid social transformation.

- Africans are a naturally religious people. As scholars have repeatedly pointed out, African cosmology does not separate the spiritual from the non-spiritual; therefore, economic, medical, and cultural spheres of reality are open to multiple interpretations.

Many charismatic leaders are recognized and respected as prophets, some with genuine histories of offering compelling spiritual leadership at significant social moments. Yet this background of good charismatic prophets, who have lengthy track records of ministry, has made it harder for most ordinary Christians to distinguish false prophets from genuine ones.

Even charismatic prophets who have served well in the past are capable of being sidetracked by fame, success, and pride to the point of becoming charlatans to maintain their image. As Jesus mentioned in that parable of the wheat and the tares, in a field that is truly alive with the rain of the Spirit of God, it is hard to distinguish the work of the devil. Therefore, we in Christian ministry and in theological reflection increasingly need to raise this issue, and to keep searching the Scriptures, to guide more Christians in the right direction.

Genuine prophets versus false: A biblical perspective

According to charismatic theology, as one of the leadership offices of the Old Testament (1 Sam 9:9, 11, 19; 2 Sam 15: 27) and New Testament (Eph 4: 11), the prophetic office is available to selected men and women (Acts 2:17). Charismatics teach that women such as Miriam (Exod 15:20), Deborah (Judges 4:4), Huldah (2 Kings 22:14; 2 Chron 34:22), Noadiah (Neh 6:14), and Anna (Luke 2:36) joined the ranks of men called to direct, build up, and mature the people of God as a God-fearing community.

Charismatics believe a prophet who is called by God serves as a reliable channel of communication between God and humanity in specific places and under specific circumstances (1 Kings 17: 1). They also might be called to reveal or predict things that are otherwise hidden, in order to restore truth, and encourage the pursuit of justice in whole nations (Amos; Jonah). A prophet might also challenge evil among leaders in the wider society (Dan 5: 13-31; Nathan in 2 Sam 12:1-12 and John the Baptist in Matt 14: 1-12).

Prophets whose intentions are self-centered or evil have been around since biblical times (Matt 7: 15-20; Acts 13: 6-12; 2 Pet 2: 1-3; Jer: 29:9). Three things distinguish a genuine prophet from false:

The African context

For many decades, the pluralistic religious worldviews of African cosmology and the obvious contemporary religiosity of Africans have been a focus for study among leading African scholars, including currently Nimi Wariboko, Opuku Onyina, Ogbu Kalu, and Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu. Ogbu Kalu argues that Africans’ worldview approaches the whole of reality through multiple cultural and religious prisms.[1] In traditional causality, understanding—and improvement of—destiny, averting evil, survival, and preservation of the good happen through religious intervention.[2]

In their many studies of religion and African society, Stephen Ellis and Gerrie Ter Haar demonstrate the importance of taking Africans’ view of reality and cosmology into account when examining the role of religion in the public sphere. Africans have no structural distinction between the visible and invisible world, though the worlds are distinguishable.[3] The connectedness of the real and the unseen worlds is controlled by supernatural forces—forces of good and evil.[4] Consciousness of these good and evil forces is a major source of fear and anxiety.[5]

In order to be free from evil attacks, one must be intentional in seeking protection from religious functionaries who have access to supernatural forces of good. This belief puts religious functionaries in a strategic position as special mediators between the realms of sacred and secular, as well as the worlds of good and evil. According to Asamoah-Gyadu, ‘religious functionaries or specialists are people who on account of their closeness to the supernatural realities, possession of mystical power or intuition, and knowledge of the workings of mysterious religious formulae and objects, occupy center stage in religion as mouthpieces of transcendent beings and powers.’[6] Africans see religious functionaries as people who possess supernatural abilities to intervene in the uncertainties of life caused by the activities of spiritual forces in the invisible world. From an African perspective, this is what explains the prevalence of the prophetic ministry, both in its genuine charismatic expression, but now, in the perverted form that is discrediting the entire church.

Some examples

Recently in South Africa, victims of alleged sexual abuse detailed their experiences to the BBC and criticized the invulnerability of so-called men of God who use their ‘prophet’ positions to cover up abuse.[7] A severe backlash against church leaders prompted the South African President to urge South Africans to unite in curbing the menace of false pastors. This was followed by a three-day public protest, led by Solomon Izang Ashoms, founder of the Movement against Abuse in Churches. That this had to be a protest involving politicians and civil activists rather than the church, suggests the church is not playing its role as the light set on a hill or the salt of the earth.

Some claims of prophetic power verge on the ludicrous and irrational. Yet in an era of social media, their claims make them even more popular as poor and desperate people look for help wherever they can. A famous self-proclaimed prophet from Zimbabwe and another from Malawi both announced they had found cures for HIV/AIDS, preventing patients from seeking medical help. A South African preacher encourages his followers to eat grass and drink petrol, while another sprays insecticide on congregants to exercise deliverance from evil.[8]

There are those who make claims that border on blasphemy. At one point, a Kenyan prophet claimed to have the powers of Moses and Elijah, and to have toured heaven and held discussions with God. In 2017, police in Oyo State in Nigeria paraded a pastor who allegedly possessed a human head and ritual paraphernalia. Elsewhere, allegations of sexual abuse and swindling people of money and property often leak out into social media.

False prophets have cunningly learnt to parrot what impoverished or troubled followers are desperate to hear. Despite awareness of the abuses, self-proclaimed prophets retain thousands of followers who fund their activities.

Government interventions

In 2016, Kenya’s attorney-general proposed a lengthy list of requirements for churches, including minimum theological education, annual membership thresholds, and affiliation to umbrella organizations.[9] However, this protocol was quickly abandoned as the government and existing church organizations lacked willpower to enforce it. One of the more successful efforts at regulatory oversight has come from the Rwandan government that has introduced strict requirements for new and existing churches. These government measures are vital, but among churches a lot more work needs to be done based on a biblically grounded perspective.

What must the church do?

This enormous challenge highlights multiple issues to be addressed. Interventions need to include evaluating existing leadership recruitment and training models, including a reconsideration of the theological curriculum used to train leaders.[10] It is urgent that the church promotes the kind of biblical literacy and discipleship that will address the contemporary problems that lead congregants to these prophets in the first place.

These solutions will require intentional collaboration and coordination. This will involve local, pan-African, and global opportunities for networking, partnership, and peer mentoring among pastoral trainers and practitioners. Conferences that focus on biblical Christianity and the discipleship of Christian ministry practitioners will be needed. Finally, those who know the truth and are concerned about the current state of the African church should be praying for the building up of its foundations and its maturity as the church of Christ in Africa.

Endnotes

- Ogbu Kalu, ‘Yabbing the Pentecostals: Paul Gifford’s Image of Ghana’s New Christianity’, African Pentecostalism: Global Discourses, Migrations and Exchange and Connects,Wilhelmina J. Kalu, Nimi Wariboko, and Toyin Fabola, eds., (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, Inc., 2010), 149-62. ↑

- Cephas N. Omenyo, and Wonderful Adjei Arthur, ‘The Bible Says! Neo-Prophetic Hermeneutics in Africa’, Studies in World Christianity, Vol. 19, No. 1 (2013), 56-57. ↑

- Stephen Ellis and Gerrie Ter Haar, ‘Religion and Politics: Taking Epistemologies African Seriously’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3 (Sep. 2007), 385-401, 377. ↑

- Ruth Marshall, ‘Pentecostalism in Southern Nigeria: An Overview’ in New Dimensions in African Christianity, ed. by Paul Gifford (Nairobi: All Africa Conference of Churches, 1992), 22. ↑

- David T. Adamo, Exploration in African Biblical Studies (Benin City: Justice Jeco Press and Publishers Limited, 2005), 54. ↑

- J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, ‘‘Blowing the Cover:’ Imagining Religious Functionaries in Ghanaian/Nigerian Films’, Religion, Media and the Marketplace, Lynn Schofield Clark, ed., (London: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 224-43. ↑

- Mbuleo Mtshilibe, ‘Fake Pastors and false Prophets rock South African faith’ in BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-47541131/fake-pastors-and-false-prophets-rock-south-african-faith. ↑

- ‘Religious Trickery Lines the Pockets of False Prophets’ in The Sunday Independent: https://www.iol.co.za/sundayindependent/dispatch/religious-trickery-lines-the-pockets-of-false-prophets-7153764/. ↑

- Tom Osanjo, ‘Kenya’s Crackdown on Fake Pastors Stymied by Real Ones’ in Christianity Today: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2016/june/kenya-crackdown-fake-pastors-stymied-real-ones.html. ↑

- Editors’ Note: See article by Ashish Chrispal, entitled, ‘Restoring Missional Vision in Theological Education’ https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-09/restoring-missional-vision-theological-education, and article by Brian Woolnough, entitled, ‘Rethinking Theological Education’ https://lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-09/rethinking-seminary-education, in September 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis. ↑

B. Moses Owojaiye, PhD, is the CEO of the Centre for Biblical Christianity in Africa. He is an alumnus of ECWA Theological Seminary, Igbaja, Nigeria, Africa International University, and the University of Edinburgh. Currently, he is a pastor of First ECWA, Ilorin and an adjunct faculty member of ECWA Theological Seminary, Igbaja.

the Bible we see that God has revealed himself to mankind as the trinity. This is impossible to understand through just observing nature. God is not only the Creator but also Saviour and Comforter. The magnificent landforms across our continent, the geographic features, the diverse creatures, the laws of nature, everything in the universe points to the evidence of a Creator (Psalms 19:1-6).

According to Paul, it is clear that African religions did not worship the self-revealing and Triune God of Scripture

God has also made himself known from the Holy Scriptures, through promises of old fulfilled in Jesus Christ, as our Saviour (Luke 24:25-27). As the Comforter, he has made himself known in the person of the Holy Spirit, in his ongoing ministry in and through the Church (Acts 2:16-21). The bottom line is that God has revealed himself to humanity through his handiwork andthrough the Scriptures. The former is referred to as general revelation and the latter as special revelation which can ultimately lead us to personal relationship with him.

Our forefathers had a conception of God. However, according to Paul, it is clear that in African Traditional Religion we do not worship the self-revealing and triune God of Scripture.

The Root of African Traditional Religion: The Suppression of Truth

In Romans 1:18-32 Paul states the root of false religion: the suppression of truth about God. In the context of the Greek religion in Rome, Paul explained that God’s wrath is evidently manifested against people who do not revere God as is his due (Romans 1:18). All forms of idolatry and false gods are rooted in men squashing the truth about God their Creator. This suppression of truth by men is done in unrighteousness or by unrighteousness. In both cases, the root is the sinful nature of every man in Adam (Romans 5:12). False religion is caused by sin in the hearts of men – the centre of men’s intellect, will and emotions – which in rebellion do not allow the knowledge of God to express itself in their lives.

The means or ways of suppressing the truth about God is captured by Paul in the context of these 5 verses:

- Not glorifying God as God (downplaying his worth and honour) and a lack of gratitude towards God (Romans 1:21)

- Barter-trading the immortal God’s glory for images of mortal creatures (Romans 1:22)

- Exchanging the truth about God for a lie by worshiping and serving the creature instead of Creator God (Romans 1:24)

- Not acknowledging God (Romans 1:28)

- Proceeding to doing and approving that which God has decreed not worthy of being done (Romans 1:32)

An Example of How the Shona Suppressed the Truth about God

The forefathers of the Shona chose to honour God with less honour than he deserved by not worshipping him alone. This can be seen in their oral poetry. These pieces of poetry, especially those for totems, reflect that animals or spirits receive honour and gratitude for God’s deeds. The mortals’ image of the Hungwe bird (Zimbabwe Bird) was glorified in the Shona Religion. This granite stone-carved resemblance was sacred in Shona religion at Great Zimbabwe. Though the Shona knew that God had all eternal power, they also reduced the power of God to spirits that governed mountains, rivers, caves, forests and sacred trees.

Though the Shona knew that God had all eternal power, they also reduced the power of God to spirits that governed mountains, rivers, caves, forests and sacred trees.

In an effort to connect with God, Shona African Traditional Religion believes that the ancestors protect mankind. It also believes that the ancestors carry our prayers to the Creator God (Musiki). The spirits of the dead and ancestors are venerated, appeased and served as mediators, sometimes more than the Creator. Jesus is the only mediator between God and man and it is impossible for our ancestors to connect us with God. Only God, through Jesus Christ his Son, watches over us and comforts us.

The Unique Root of Christianity: The Expression of Truth

Whereas African Traditional Religion has a distorted view of God by suppressing His truth about himself, Christianity starts with expressing the truth about God. Christians acknowledge all that God has done, and can be known about Him known through general revelation (the creation) as well as through and in special revelation (the Bible). Special revelation acknowledges truth about God which we see in general revelation.

Our forefathers in different parts of Africa did not fully acknowledge all that God was as the Creator. Three men stood against our forefathers and acknowledged God as the Creator and all he did as Creator, prior to the era of any special revelation (Hebrews 11:4-7). Abel, Enoch and Noah. These three were declared righteous upon acknowledging God as the Creator.

The hope in the promises of God was missing in the religions of our forefathers. They had the knowledge of God’s creative deeds but lacked the promises.

What God Has Done and What God Promises to do

Though these men acknowledged God through all His deeds, they also hoped for that which God promised. Christians acknowledge the truth about God: what He has done in the past and hope in the promises of God for tomorrow. Abel, Enoch and Noah hoped in the promised ‘serpent crusher’, the seed of the woman to come (Genesis 3:15). Our forefathers forgot or suppressed God’s truth in this promise as they moved from Mount Ararat and then to the Tower of Babel. The hope in the promises of God was missing in the religions of our forefathers. They had the knowledge of God’s creative deeds but lacked the promises.

When the book of Hebrews speaks about these two sides of the same coin that make up true religion, it shows us that all who were declared righteous by God were anchored in that which God had done and in the hope of that which God will do. This is saving faith (Hebrews 11:1-3). Unrighteous people are made righteous through faith. This is the principle that Paul speaks about in the context of Romans 1:18. True religion starts with faith which is being convinced of what God has done and what God will do – in Jesus Christ – and from this faith, people are made righteous.

Christianity and African Traditional Religion are Different

Our children ought to know the difference between African Traditional Religion and Christianity, for their salvation is at stake. African Traditional Religion suppresses the truth of the knowledge of God and the deeds of God. Christianity expresses God’s truth and deeds.

African Traditional Religion is an expression of humanity’s inherited unrighteousness from the sin of Adam. Christianity is an expression of the righteousness gained through faith in Christ. African religions have a distorted and belittling view of God, yet Christianity has a full and comprehensive view of God. Unlike Christianity, African Traditional Religion lacks the promise in the Saviour and Comforter. Christianity rightly glorifies God, but African religion reveres creatures, be it animal or human ancestral spirits. Praise God for his grace in revealing himself through the Scriptures that we may know and worship him in truth!

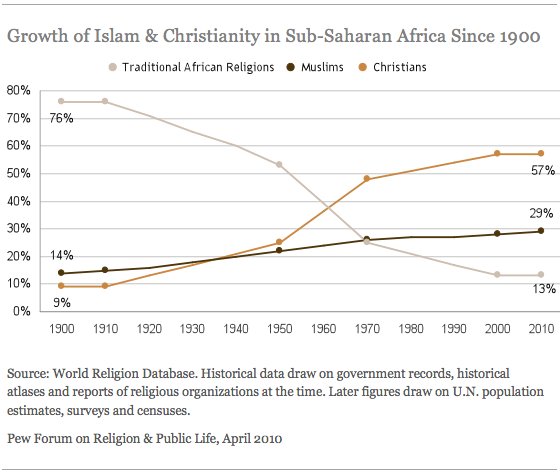

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

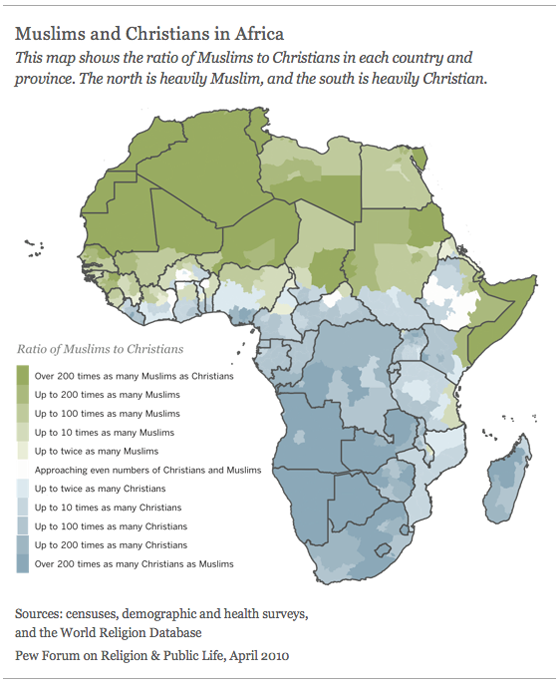

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world’s Muslims (15%).1 While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west. To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda’s first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda’s first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

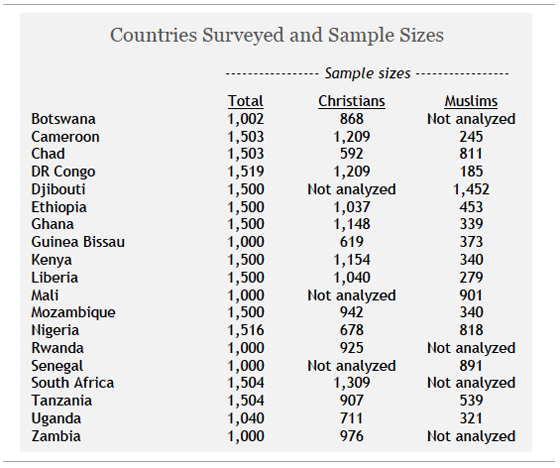

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

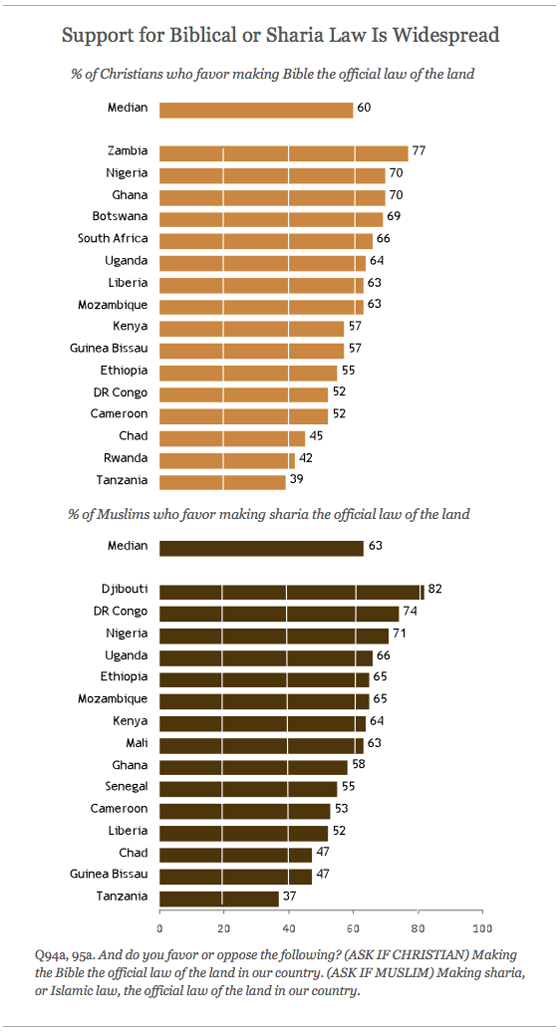

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort – the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project – that aims to increase people’s knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world’s two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practiceshave not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people’s lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

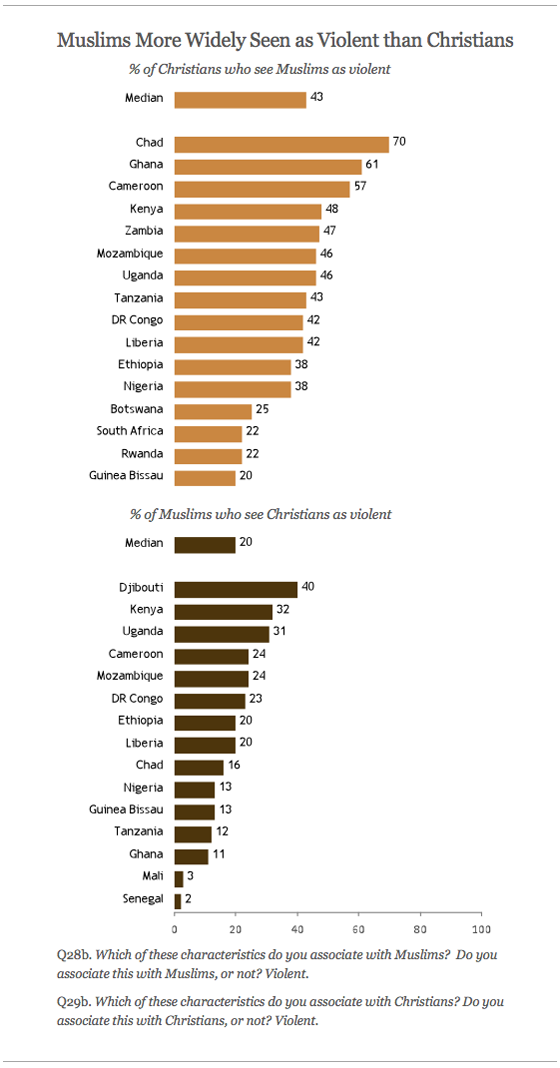

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other’s faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Other Findings

In addition, the 19-nation survey finds:

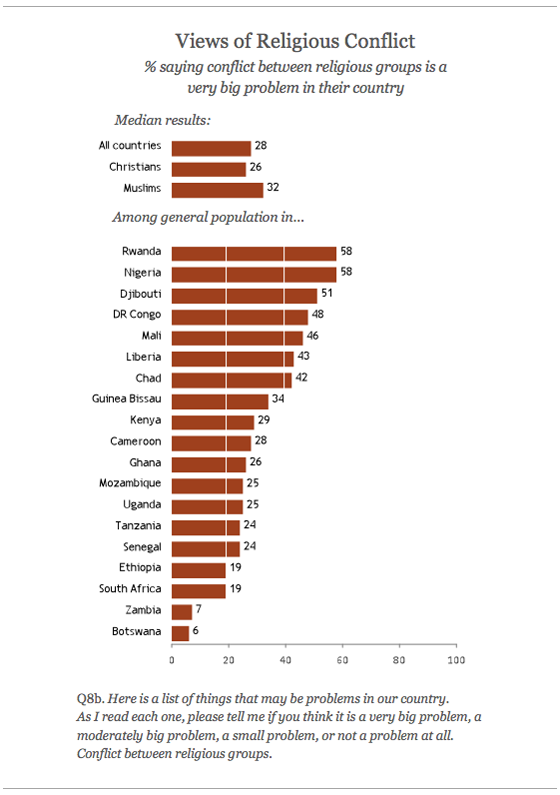

- Africans generally rank unemployment, crime and corruption as bigger problems than religious conflict. However, substantial numbers of people (including nearly six-in-ten Nigerians and Rwandans) say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country.

- The degree of concern about religious conflict varies from country to country but tracks closely with the degree of concern about ethnic conflict in many countries, suggesting that they are often related.

- Many Africans are concerned about religious extremism, including within their own faith. Indeed, many Muslims say they are more concerned about Muslim extremism than about Christian extremism, and Christians in four countries say they are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism.

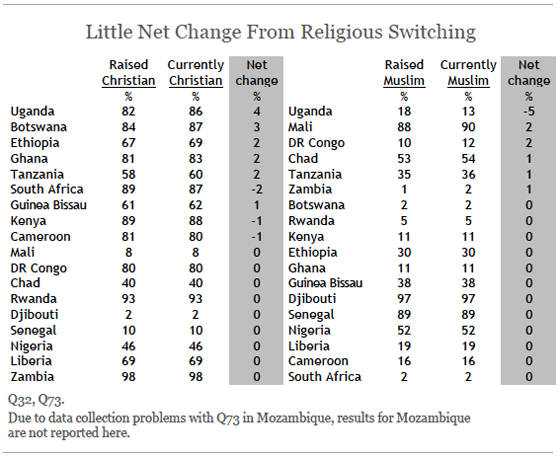

- Neither Christianity nor Islam is growing significantly in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other; there is virtually no net change in either direction through religious switching.

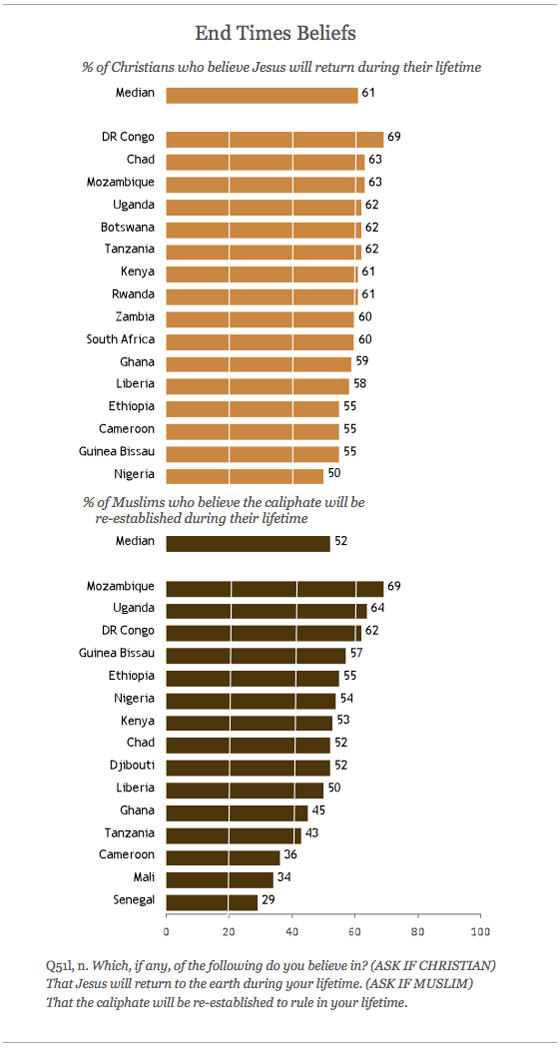

- At least half of all Christians in every country surveyed expect that Jesus will return to earth in their lifetime, while roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to live to see the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule.

- People who say violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion is rarely or never justified vastly outnumber those who say it is sometimes or often justified. But substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion is sometimes or often justified.

- In most countries, at least half of Muslims say that women should not have the right to decide whether to wear a veil, saying instead that the decision should be up to society as a whole.

- Circumcision of girls (female genital cutting) is highest in the predominantly Muslim countries of Mali and Djibouti but is more common among Christians than among Muslims in Uganda.

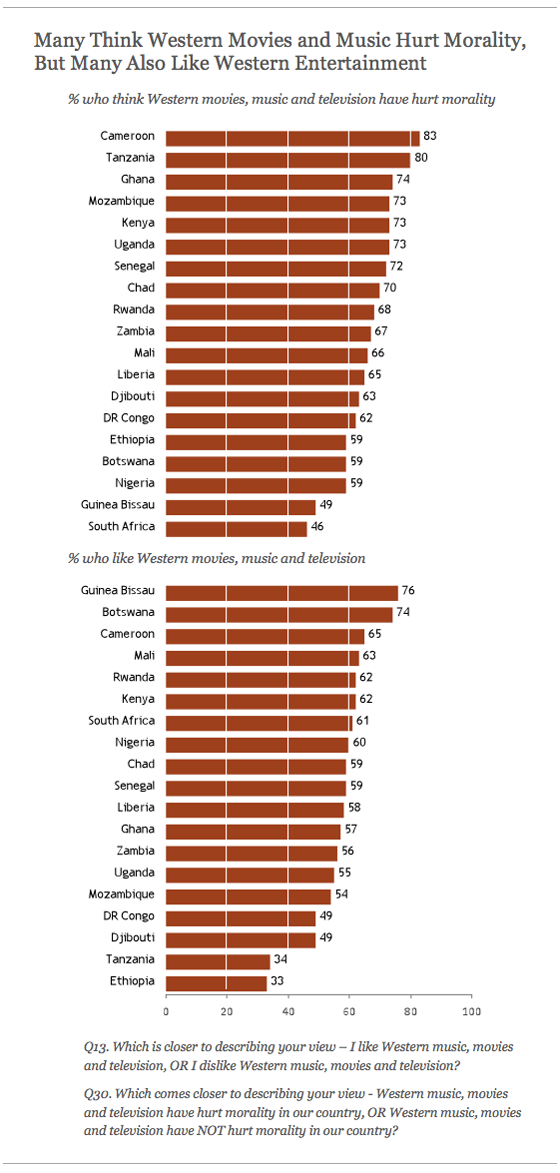

- Majorities in almost every country say that Western music, movies and television have harmed morality in their nation. Yet majorities in most countries also say they personally like Western entertainment.

- In most countries, more than half of Christians believe in the prosperity gospel – that God will grant wealth and good health to people who have enough faith.

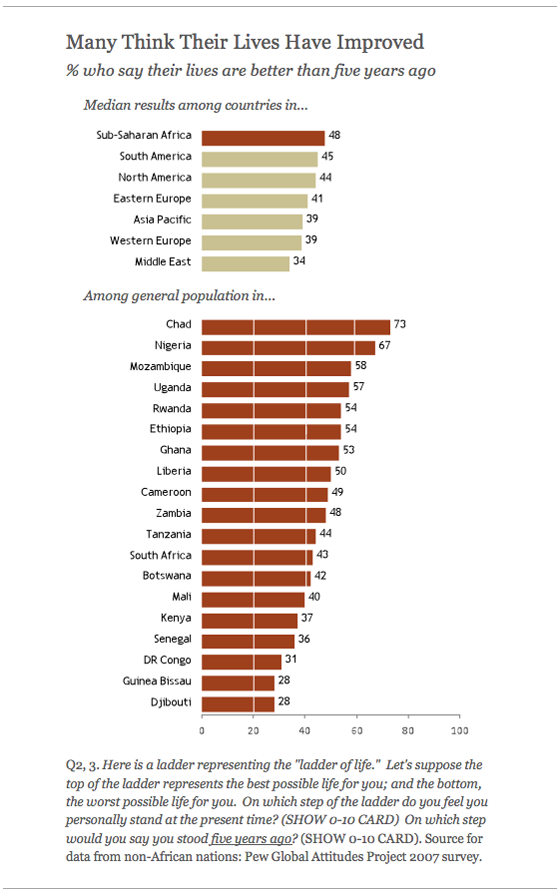

- By comparison with people in many other regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africans are much more optimistic that their lives will change for the better.

Adherence to Islam and Christianity

Large majorities in all the countries surveyed say they believe in one God and in heaven and hell, and large numbers of Christians and Muslims alike believe in the literal truth of their scriptures (either the Bible or the Koran). Most people also say they attend worship services at least once a week, pray every day (in the case of Muslims, generally five times a day), fast during the holy periods of Ramadan or Lent, and give religious alms (tithing for Christians, zakat for Muslims; see the glossary of terms for more information about tithing and zakat).

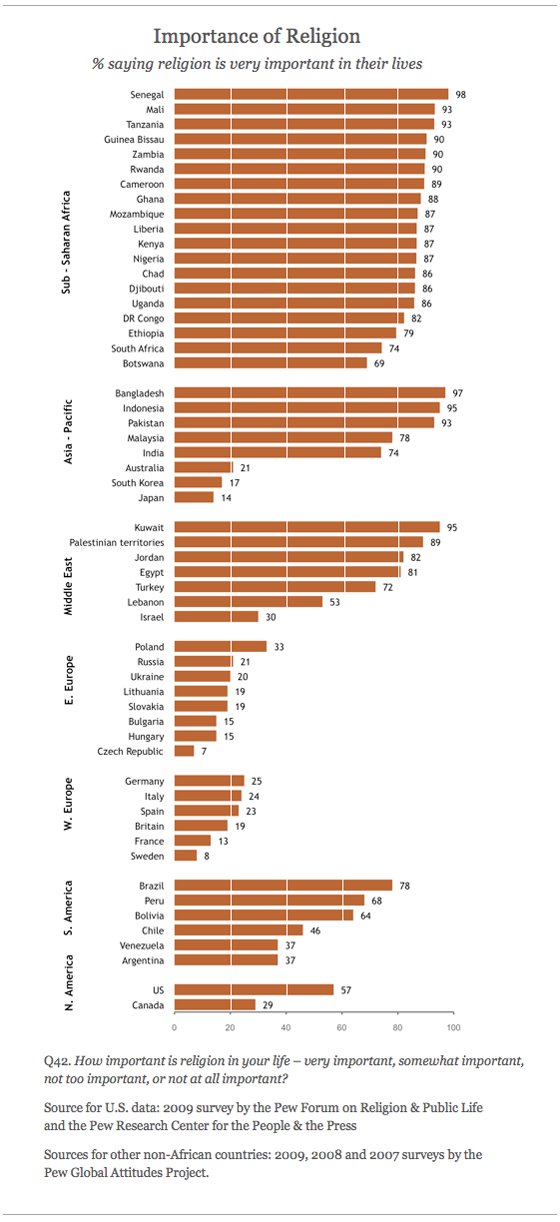

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa is clearly among the most religious places in the world. In many countries across the continent, roughly nine-in-ten people or more say religion is very important in their lives. By this key measure, even the least religiously inclined nations in the region score higher than the United States, which is among the most religious of the advanced industrial countries.

Persistence of Traditional African Religious Practices

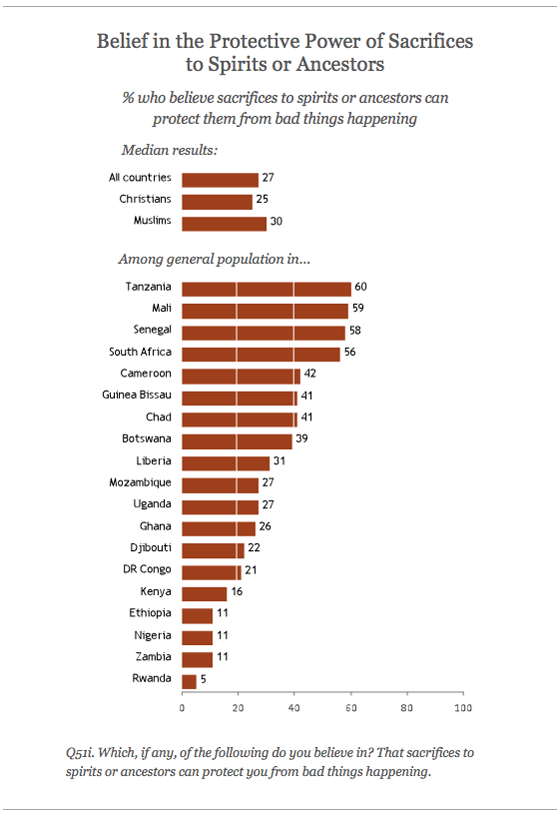

At the same time, many of those who indicate they are deeply committed to the practice of Christianity or Islam also incorporate elements of African traditional religions into their daily lives. For example, in four countries (Tanzania, Mali, Senegal and South Africa) more than half the people surveyed believe that sacrifices to ancestors or spirits can protect them from harm. Sizable percentages of both Christians and Muslims – a quarter or more in many countries – say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets). Many people also say they consult traditional religious healers when someone in their household is sick, and sizable minorities in several countries keep sacred objects such as animal skins and skulls in their homes and participate in ceremonies to honor their ancestors. And although relatively few people today identify themselves primarily as followers of a traditional African religion, many people in several countries say they have relatives who identify with these traditional faiths.

Sizable percentages of both Christians and Muslims – a quarter or more in many countries – say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets). Many people also say they consult traditional religious healers when someone in their household is sick, and sizable minorities in several countries keep sacred objects such as animal skins and skulls in their homes and participate in ceremonies to honor their ancestors. And although relatively few people today identify themselves primarily as followers of a traditional African religion, many people in several countries say they have relatives who identify with these traditional faiths.

Handed down over generations, indigenous African religions have no formal creeds or sacred texts comparable to the Bible or Koran. They find expression, instead, in oral traditions, myths, rituals, festivals, shrines, art and symbols. In the past, Westerners sometimes described them as animism, paganism, ancestor worship or simply superstition, but today scholars acknowledge the existence of sophisticated African traditional religions whose primary role is to provide for human well-being in the present as opposed to offering salvation in a future world.

Because beliefs and practices vary across ethnic groups and regions, some experts perceive a multitude of different traditional religions in Africa. Others point to unifying themes and, thus, prefer to think of a single faith with local differences.

In general, traditional religion in Africa is characterized by belief in a supreme being who created and ordered the world but is often experienced as distant or unavailable to humans. Lesser divinities or spirits who are more accessible are sometimes believed to act as intermediaries. A number of traditional myths explain the creation and ordering of the world and provide explanations for contemporary social relationships and norms. Lapsed social responsibilities or violations of taboos are widely believed to result in hardship, suffering and illness for individuals or communities and must be countered with ritual acts to re-establish order, harmony and well-being.

Ancestors, considered to be in the spirit world, are believed to be part of the human community. Believers hold that ancestors sometimes act as emissaries between living beings and the divine, helping to maintain social order and withdrawing their support if the living behave wrongly. Religious specialists, such as diviners and healers, are called upon to discern what infractions are at the root of misfortune and to prescribe the appropriate rituals or traditional medicines to set things right.

African traditional religions tend to personify evil. Believers often blame witches or sorcerers for attacking their life-force, causing illness or other harm. They seek to protect themselves with ritual acts, sacred objects and traditional medicines. African slaves carried these beliefs and practices to the Americas, where they have evolved into religions such as Voodoo in Haiti and Santeria in Cuba. (back to text)

Tolerance, but Also Tensions

The survey finds that on several measures, many Muslims and Christians hold favorable views of each other. Muslims generally say Christians are tolerant, honest and respectful of women, and in most countries half or more Christians say Muslims are honest, devout and respectful of women. In roughly half the countries surveyed, majorities also say they trust people who have different religious values than their own.

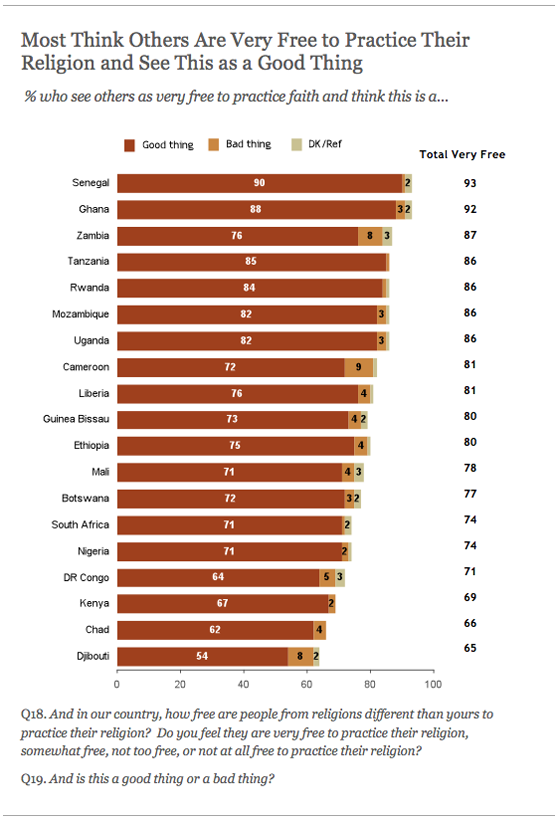

Sizable majorities in every country surveyed say that people of different faiths are very free to practice their religion, and most add that this is a good thing rather than a bad thing. In most countries, majorities say it is all right if their political leaders are of a different religion than their own. And in most countries, significant minorities (20% or more) of people who attend religious services say that their mosque or church works across religious lines to address community problems.

On the other hand, the survey also reveals clear signs of tension and division. Overall, Christians are less positive in their views of Muslims than Muslims are of Christians; substantial numbers of Christians (ranging from 20% in Guinea Bissau to 70% in Chad) say they think of Muslims as violent. In a handful of countries, a third or more of Christians say many or most Muslims are hostile toward Christians, and in a few countries a third or more of Muslims say many or most Christians are hostile toward Muslims.

| What Is a Median? |

The median is the middle number in a list of numbers sorted from highest to lowest. For many questions in this report, medians are shown to help readers see differences between Muslim and Christian subpopulations and general populations, or to highlight differences between sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world.

In charts showing results from all 19 countries on a particular question, the median for “all countries” is the 10th spot on the list. In charts where there is an even number of countries in the list and there is no country exactly in the middle, the median is computed as the average of the two countries at the middle of the list (e.g., where 16 nations are shown, the median is the average of the 8th and 9th countries on the list).

To help readers see whether Muslims and Christians differ significantly on certain questions, separate medians for Christians and Muslims also are shown. The median for Christians is based on the survey results among Christians in each of the 16 countries with a Christian population large enough to analyze. The median for Muslims is based on the survey results among Muslims in each of the 15 countries with a Muslim population large enough to analyze.

By their own reckoning, neither Christians nor Muslims in the region know very much about each other’s faith. In most countries, fewer than half of Christians say they know either some or a great deal about Islam, and fewer than half of Muslims say they know either some or a great deal about Christianity. Moreover, people in most countries surveyed, especially Christians, tend to view the two faiths as very different rather than as having a lot in common. And many people say they are not comfortable with the idea of their children marrying a spouse from outside their religion.

People throughout the region generally see conflict between religious groups as a modest problem compared with other issues such as unemployment, crime and corruption. Still, substantial numbers in all the countries surveyed except Botswana and Zambia say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country, reaching a high of 58% in Nigeria and Rwanda. In addition, substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say that violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion can sometimes or often be justified. And large numbers (more than 40%) in nearly every country express concern about extremist religious groups in their nation, including within their own religious community in some instances. Indeed, in almost all countries in which Muslims constitute at least 10% of the population, Muslims are more concerned about Muslim extremism than they are about Christian extremism, while in a few overwhelmingly Christian countries, including South Africa, Christians are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism. And in many countries, sizable numbers express concern about both Muslim and Christian extremism.

Support for Both Democracy and Religious Law

Across the sub-Saharan region, large numbers of people express strong support for democracy and say it is a good thing that people from religions different than their own are able to practice their faith freely. Asked whether democracy is preferable to any other kind of government or “in some circumstances, a nondemocratic government can be preferable,” strong majorities in every country choose democracy. In most places there is no significant difference between Muslims and Christians on this question.

At the same time, there is substantial backing from both Muslims and Christians for basing civil laws on the Bible or sharia law. This may simply reflect the importance of religion in Africa. But it is nonetheless striking that in virtually all the countries surveyed, a majority or substantial minority (a third or more) of Christians favor making the Bible the official law of the land, while similarly large numbers of Muslims say they would like to enshrine sharia, or Islamic law. Majorities of Muslims in nearly all the countries surveyed support allowing leaders and judges to use their religious beliefs when deciding family and property disputes, as do sizable minorities (30% or more) of Christians in most countries. Similarly, the survey finds considerable support among Muslims in several countries for the application of criminal sanctions such as stoning people who commit adultery, and whipping or cutting off the hands of thieves. Support for these kinds of punishments is consistently lower among Christians than among Muslims. The survey also finds that in seven countries, roughly one-third or more of Muslims say they support the death penalty for those who leave Islam.

Majorities of Muslims in nearly all the countries surveyed support allowing leaders and judges to use their religious beliefs when deciding family and property disputes, as do sizable minorities (30% or more) of Christians in most countries. Similarly, the survey finds considerable support among Muslims in several countries for the application of criminal sanctions such as stoning people who commit adultery, and whipping or cutting off the hands of thieves. Support for these kinds of punishments is consistently lower among Christians than among Muslims. The survey also finds that in seven countries, roughly one-third or more of Muslims say they support the death penalty for those who leave Islam.

The End of Christian and Muslim Expansion?

While the survey finds that both Christianity and Islam are flourishing in sub-Saharan Africa, the results suggest that neither faith may expand as rapidly in this region in the years ahead as it did in the 20th century, except possibly through natural population growth. There are two main reasons for this conclusion. First, the survey shows that most people in the region have committed to Christianity or Islam, which means the pool of potential converts from outside these two faiths has decreased dramatically. In most countries surveyed, 90% or more describe themselves as either Christians or Muslims, meaning that fewer than one-in-ten identify as adherents of other faiths (including African traditional religions) or no faith.

Second, there is little evidence in the survey findings to indicate that either Christianity or Islam is growing in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other. Although a relatively small percentage of Muslims have become Christians, and a relatively small percentage of Christians have become Muslims, the survey finds no substantial shift in either direction. One exception is Uganda, where roughly one-third of respondents who were raised Muslim now describe themselves as Christian, while far fewer Ugandans who were raised Christian now describe themselves as Muslim.

Intense Religious Experiences and the Influence of Pentecostalism

Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa experience their respective faiths in a very intense, immediate, personal way. For example, three-in-ten or more of the people in many countries say they have experienced a divine healing, witnessed the devil being driven out of a person or received a direct revelation from God. Moreover, in every country surveyed that has a substantial Christian population, at least half of Christians expect that Jesus will return to earth during their lifetime. And in every country surveyed that has a substantial Muslim population, roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to personally witness the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule that followed the death of Muhammad. Many of these intense religious experiences, including divine healings and exorcisms, are also characteristic of traditional African religions. Within Christianity, these kinds of experiences are particularly associated with Pentecostalism, which emphasizes such gifts of the Holy Spirit as speaking in tongues, giving or interpreting prophecy, receiving direct revelations from God, exorcising evil and healing through prayer. About a quarter of all Christians in four sub-Saharan countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria) now belong to Pentecostal denominations, as do at least one-in-ten Christians in eight other countries. But the survey finds that divine healings, exorcisms and direct revelations from God are commonly reported by African Christians who are not affiliated with Pentecostal churches.

Many of these intense religious experiences, including divine healings and exorcisms, are also characteristic of traditional African religions. Within Christianity, these kinds of experiences are particularly associated with Pentecostalism, which emphasizes such gifts of the Holy Spirit as speaking in tongues, giving or interpreting prophecy, receiving direct revelations from God, exorcising evil and healing through prayer. About a quarter of all Christians in four sub-Saharan countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria) now belong to Pentecostal denominations, as do at least one-in-ten Christians in eight other countries. But the survey finds that divine healings, exorcisms and direct revelations from God are commonly reported by African Christians who are not affiliated with Pentecostal churches.

Morality and Culture