So let’s look at this from God’s perspective. We are to rule over sin, and it has no dominion over us. I believe this is why some people (like myself who has the Holy Spirit) can drink one drink and literally be fine like we do not crave it… and those who don’t believe and who have not the Holy Spirit cannot do this. So I was born again and my whole mindset changed and I actually gave myself permission to drink because God actually gave us alcohol to enjoy. Believe it or not, there’s no such thing as alcoholism in the Bible. Now, there’s drunkenness which is sun and there are drunkards and we will be talking about all of this today! The truth sets people FREE!

I personally drink wine because I am free to do so in Christ, and nothing I drink will poison me. I firmly believe this and this is what the Bible says. So alcohol literally has no "affect" on my character because I am sealed with the Holy Spirit. Now, we are to be fully convinced in our own mindt. We are to be careful in front of weaker believers, because they might not unerstand that we can do that. The bible does NOT condemn drinking, only drunkards and drunkenness. There s tons of verses that steer clear of drinking, and there's also a lot that like Solomon says, drink o Beloved! It is a personal conviction that we all must have before God. But I am here to tell you the Bible changed my thinking from "alcohol is wrong/bad" to Mark 16:18 NOTHING I drink shall poison me. The devil tempted Eve to question God's word which we have all been there. We need to believe God's word and walk in the Kingdom authority that we have been given.

Where is The True Origin of Wine?

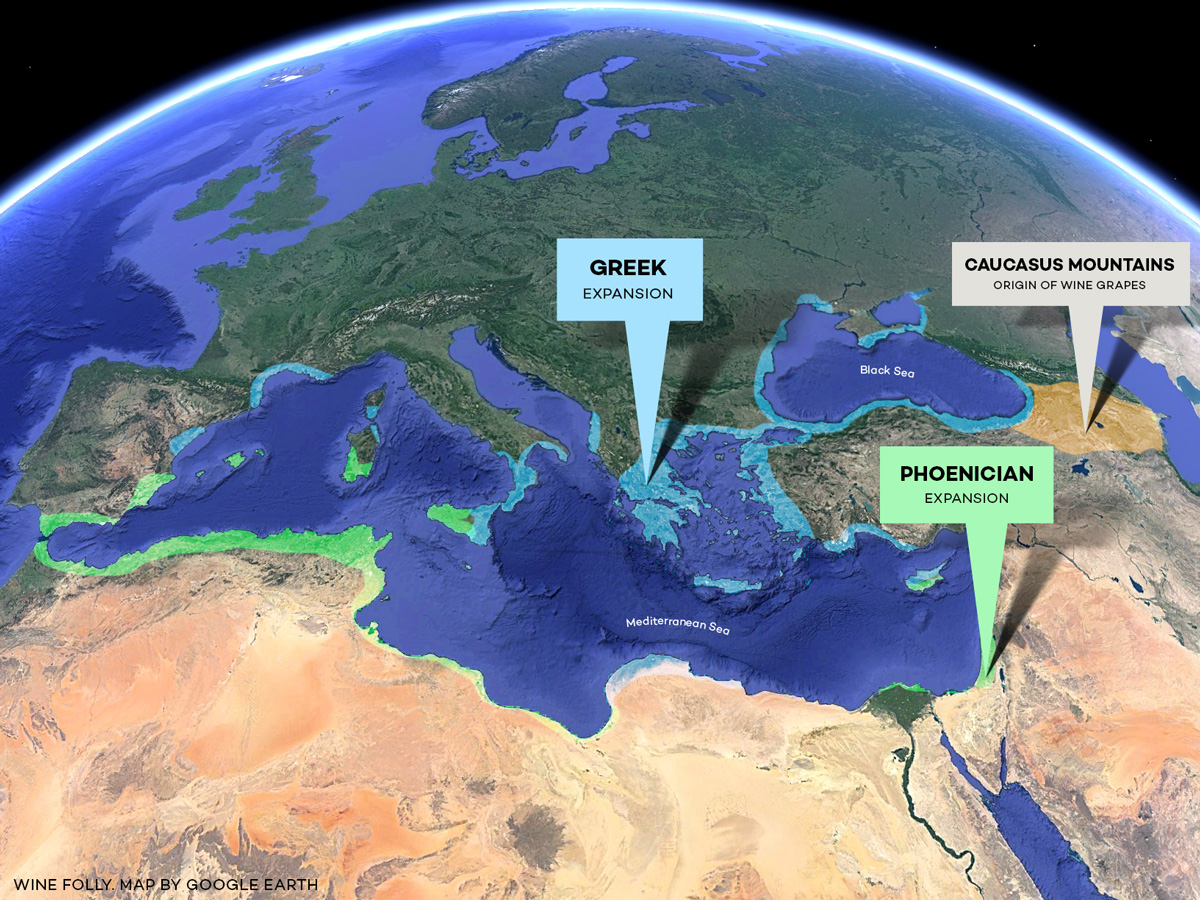

Current evidence suggests that wine originated in West Asia including Caucasus Mountains, Zagros Mountains, Euphrates River Valley, and Southeastern Anatolia. This area spans a large area that includes the modern day nations of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, northern Iran, and eastern Turkey.

Ancient wine production evidence dates around 4000 BC, and includes an ancient winery site in Armenia, grape residue found in clay jars in Georgia, and signs of grape domestication in eastern Turkey. We still haven’t pin-pointed the specific origin of wine, but we think we know who made it!

The Shulaveri-Shomu people (or “Shulaveri-Shomutepe Culture”) are thought to be the earliest people making wine in this area. This was during the Stone Age (neolithic period) when people used obsidian for tools, raised cattle and pigs, and most importantly, grew grapes.

Here are some examples of what we’ve learned about the origin of wine.

Wine in 4,000 BC

Organic compounds found in ancient Georgian pottery link winemaking to an area in the Southern Caucasus. The pottery vessels, called Kvevri (or Qvevri), can still be found in modern winemaking in Georgia today!

Wild Vines in Southeastern Anatolia

By studying grape genetics, José Vouillimoz (a grape “ampelologist”), identified a region in Turkey where wild grape vines closely resemble cultivated vines. This research supports a theory that a convergence zone between cultivated and wild vines could be the origin place of winemaking!

A Relic Winery Unearthed in Armenia

The oldest known winery (4,100 BC) exists in group of caves outside the Armenian village of Areni. The village is still known for winemaking and makes red wines with a local grape also called Areni. Areni is thought to be quite old and you can still drink it today!

Ancient Wine Influencers: The Phoenicians and Greeks

From West Asia, wine grapes followed cultures as they expanded into the Mediterranean. Sea-fairing civilizations including the Phoenicians and Greeks spread wine throughout much of Europe. As grapes came into new areas they slowly mutated to survive new climates.

The mutations created new grape varieties or “cultivars” of the wine grape species. This is why we have several thousands of wine grapes today!

Diversity is important. In wine, diversity protects against disease and reduces the need for pesticides. Additionally, different grapes thrive in different climates. This gives us the opportunity to grow wine grapes in many places.

Unfortunately, demand for popular grapes reduces the amount of natural diversity in the world. Many ancient regions (with rare varieties) pull out their native grapevines in favor of popular varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon or Pinot Noir.

Planting familiar grapes is more common that you might think. For example, about 50 grapes make up about 70% of the world’s vineyards. Current vineyard statistics suggest that there are over 700,000 acres (288k hectares) of Cabernet Sauvignon.Whereas, some rare varieties only exist in a single vineyard!

Drink New Wines From Old Grapes

If you love wine, make an effort to try new wines; it encourages diversity! To that effort, we’ve created a starter collection of over 100 grape varieties that you might like to try! I hope you enjoyed this exploration of the origin of wine and explore the collection below.

Wine plays a significant role in the Bible, with more than 140 references to this delicious fruit of the vine. From the days of Noah in Genesis (Genesis 9:18–27) to the time of Solomon (Song of Solomon 7:9) and on through the New Testament to the book of Revelation (Revelation 14:10), wine appears in the biblical text.

A standard drink in the ancient world, wine was one of God’s special blessings to bring joy to His people’s hearts (Deuteronomy 7:13; Jeremiah 48:33; Psalm 104:14–15). Yet the Bible makes it clear that overindulgence and abuse of wine are dangerous practices that can ruin one’s life (Proverbs 20:1; 21:17).

Wine in the Bible

- Wine, which gladdens the heart, is one of God’s special blessings to His people.

- Wine in the Bible symbolizes life, vitality, joy, blessing, and prosperity.

- In the New Testament, wine represents the blood of Jesus Christ.

- The Bible is clear that consuming wine in excess can do great harm to those who misuse it in this way.

Wine comes from the fermented juice of grapes—a fruit grown widely throughout the ancient holy lands. In Bible times, ripened grapes were gathered from vineyards in baskets and brought to the winepress. The grapes were crushed or treaded on a large flat rock so that the juice pressed out and flowed down through shallow canals into a giant stone vat at the foot of the winepress.

The grape juice was collected into jars and set aside to ferment in a cool, natural cave or hewn cistern where the appropriate fermentation temperature could be retained. Many passages indicate that the color of wine in the Bible was red like blood (Isaiah 63:2; Proverbs 23:31).

Wine in the Old Testament

Wine symbolized life and vitality. It was also a sign of joy, blessing, and prosperity in the Old Testament (Genesis 27:28). Called “strong drink” thirteen times in the Old Testament, wine was a potent alcoholic beverage and aphrodisiac. Other names for wine in the Bible are “the blood of grapes” (Genesis 49:11); “wine of Hebron” (Ezekiel 27:18); “new wine” (Luke 5:38); “aged wine” (Isaiah 25:6); “spiced wine;” and “pomegranate wine” (Song of Solomon 8:2).

Throughout the Old Testament, partaking of wine was associated with happiness and celebration (Judges 9:13; Isaiah 24:11; Zechariah 10:7; Psalm 104:15; Ecclesiastes 9:7; 10:19). The Israelites were commanded to make drink offerings of wine and tithesof wine (Numbers 15:5; Nehemiah 13:12).

Wine featured prominently in several Old Testament stories. In Genesis 9:18–27, Noah planted a vineyard after leaving the ark with his family. He became drunk on wine and lay uncovered in his tent. Noah’s son Hamsaw him naked and disrespected his father to his brothers. When Noah found out, he cursed Ham and his descendants. This occasion was the first incident in the Bible showing the devastation that drunkenness can cause to oneself and one’s family.

In Proverbs 20:1, wine is personified: “Wine is a mocker, strong drink a brawler, and whoever is led astray by it is not wise” (Proverbs 20:1, ESV). “Those who love pleasure become poor; those who love wine and luxury will never be rich,” informs Proverbs 21:17 (NLT).

Even though wine was God’s gift to bless His people with joy, its misuse led them to abandon the Lord to worship idols (Hosea 2:8; 7:14; Daniel 5:4). God’s wrath is also pictured as a cup of wine poured out in judgment (Psalm 75:8).

In Song of Solomon, wine is the drink of lovers. “May your kisses be as exciting as the best wine,” declares Solomon in verse 7:9 (NLT). Song of Solomon 5:1 lists wine among the ingredients of love-making between lovers: “[Young Man] I have entered my garden, my treasure, my bride! I gather myrrh with my spices and eat honeycomb with my honey. I drink wine with my milk. [Young Women of Jerusalem] Oh, lover and beloved, eat and drink! Yes, drink deeply of your love!” (NLT). In various passages, the love between the two is described as better and more praiseworthy than wine (Song of Solomon 1:2, 4; 4:10).

In ancient times, wine was consumed undiluted, and wine mixed with water was considered spoiled or ruined (Isaiah 1:22).

Wine in the New Testament

In the New Testament, wine was stored in flasks made from animal skins. Jesus applied the concept of old and new wineskins to illustrate the difference between the old and new covenants(Matthew 9:14–17; Mark 2:18–22; Luke 5:33–39).

When wine ferments, it produces gasses that stretch the wineskins. New leather can expand, but older leather loses its flexibility. New wine in old wineskins would crack the leather, causing the wine to spill out. The truth of Jesus as Savior could not be contained within the former confines of self-righteous, pharisaical religion. The old, dead way was too dried up and unresponsive to carry the fresh message of salvation in Jesus Christ to the world. God would use His church to accomplish the goal.

In Jesus’ life, wine served to demonstrate His glory, as seen in Christ’s first miracle of turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1–12). This miracle also signaled that Israel’s Messiah would bring joy and blessing to His people.

According to some Bible scholars, the wine of the New Testament was diluted with water, which may have been accurate in specific uses. But wine had to have been strong enough to intoxicate for the apostle Paul to warn, “Do not get drunk on wine, which leads to debauchery. Instead, be filled with the Spirit” (Ephesians 5:1, NIV).

Sometimes wine was mixed with spices like myrrh as an anesthetic (Mark 15:23). Drinking wine was also recommended to relieve the wounded or sick (Proverbs 31:6; Matthew 27:34). The apostle Paul instructed his young protégé, Timothy, “Don’t drink only water. You ought to drink a little wine for the sake of your stomach because you are sick so often” (1 Timothy 5:23, NLT).

Wine and the Last Supper

When Jesus Christ commemorated the Last Supper with His disciples, He used wine to represent His blood which would be poured out in sacrifice for the sins of the world through His suffering and death on the cross (Matthew 26:27–28; Mark 14:23–24; Luke 22:20). Everyone who remembers His death and looks forward to His return partakes in the new covenant confirmed with His blood (1 Corinthians 11:25). When Jesus Christ comes again, they will join Him in a great celebratory feast (Mark 14:25; Matthew 26:29; Luke 22:28–30; 1 Corinthians 11:26).

Today, the Christian Church continues to celebrate the Lord’s Supper as He commanded. In many traditions, including the Catholic Church, fermented wine is used in the sacrament. Most Protestant denominations now serve grape juice. (Nothing in the Bible commands or forbids using fermented wine in Communion.)

Differing theological views exist regarding the elements of bread and wine in Communion. The “real presence” view believes that Jesus Christ’s body and blood are physically present in the bread and wine during the Lord’s Supper. The Roman Catholic position holds that once the priest has blessed and consecrated the wine and the bread, the body and blood of Christ become literally present. The wine transforms into Jesus’ blood, and the bread becomes His body. This change process is known as transubstantiation. A slightly different view believes Jesus is genuinely present, but not physically.

Another view is that Jesus is present in a spiritual sense, but not literally in the elements. Reformed churches of the Calvinist view take this position. Finally, the “memorial” view accepts that the elements do not change into the body and blood but instead function as symbols, representing Christ’s body and blood, in memory of the Lord’s enduring sacrifice. Christians who hold this position believe Jesus was speaking in figurative language at the Last Supper to teach spiritual truth. Drinking His blood is a symbolic action that represents receiving Christ wholly into one's life and not holding anything back.

Wine factors richly throughout the biblical narrative. Its value is identified in agricultural and economic industries as well as in bringing gladness to people’s hearts. Simultaneously, the Bible warns against excessive drinking of wine and even advocates for total abstinence in some situations (Leviticus 10:9; Judges 13:2–7; Luke 1:11–17; Luke 7:33).

What is wine? Wine is the fermented juice of crushed grapes; an alcoholic beverage that can lead to intoxication if consumed in excess. Most of us know what wine is, though some teachers have attempted to explain that the wine in Scripture is sometimes wine, and sometimes grape juice. The plain truth is the best biblical scholars argue consistently and clearly, that not only is the "wine" of the Bible alcoholic, maintaining unfermented grape juice would be a virtual impossibility. D.F. Watson states it plainly in The Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels in his article, Wine, when he says, "All wine mentioned in the Bible is fermented grape juice with an alcohol content. No non-fermented drink was called wine."

Who Drank Wine in the Bible?

Who drank wine in the Bible? Almost everyone. Drinking wine was normative for all Jews, (Gen 14:18; Judges 19:19; 1 Sam. 16:20), though the Levitical priests in service at the temple (Lv 10:8, 9), the Nazirites (Num. 6:3), and the Rechabites (Jer 35:1–3) abstained from wine. In the New Testament John The Baptist also abstained.

Despite what some today claim, Jesus himself drank wine (Lk. 22:18; Matt. 11:18-19; 26:27-29), and was charged with drinking too much by his accusers.

“For John came neither eating nor drinking, and they say, ‘He has a demon.’ The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and they say, ‘Look at him! A glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners!’ Yet wisdom is justified by her deeds.””

How is Wine Depicted in Scripture?

Wine was the common drink of the Jews, enjoyed with meals and shared with friends (Gen. 14:18; Jn. 2:3). It was also an essential part in the worship of the people of God in both Testaments.

The “drink offering” consisted of wine (Ex 29:40; Lev. 23:13) and the people of God brought wine when offering sacrifices (1 Sm 1:24). The Jews even kept wine in the temple (1 Chr 9:29). In Isaiah 62:9 the people are blessed by the Lord in such a way as is depicted in drinking wine in the sanctuary before the presence of God. In Deuteronomy 14 we read,

“You shall tithe all the yield of your seed that comes from the field year by year. And before the LORD your God, in the place that he will choose, to make his name dwell there, you shall eat the tithe of your grain, of your wine, and of your oil, and the firstborn of your herd and flock, that you may learn to fear the LORD your God always. And if the way is too long for you, so that you are not able to carry the tithe, when the LORD your God blesses you, because the place is too far from you, which the LORD your God chooses, to set his name there, then you shall turn it into money and bind up the money in your hand and go to the place that the LORD your God chooses and spend the money for whatever you desire—oxen or sheep or wine or strong drink, whatever your appetite craves. And you shall eat there before the LORD your God and rejoice, you and your household. And you shall not neglect the Levite who is within your towns, for he has no portion or inheritance with you.”

Wine was used in celebrating the Passover and is used in celebrating The Lord’s Supper in the New Testament (Lk. 22:7-23; 1 Cor. 11:17-32). For more information read my blogpost, Wine or Welch's?

It was also used medicinally, to help the weak and the sick (2 Sm 16:2; Prov 31:6; 1 Tim. 5:23).

It isn't a stretch to say that God likes wine. It was associated with life, God’s blessing, and God’s Kingdom. In Judges 9:13 we read that wine is that “which cheers God and men.” Psalm 104:15 portrays wine similarly, saying that wine “makes man’s heart glad” (Ecc. 10:19; Is. 55:1, 2; Zech. 10:7). (See Walter A. Elwell and Barry J. Beitzel, Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible). Even the future fulfillment of the Kingdom of God will be characterized by the abundance of wine (Is. 25:6-8; Amos 9:13).

Of course, not every reference to wine in the Bible is positive. Drunkenness is condemned, and God's people are warned against the danger of intoxication (Is. 28:1-7; Eph 5:18; Is. 5:11; Titus 2:3).

In his book, What Would Jesus Drink, Brad Whittington breaks down the biblical references of alcohol into three types. In all, there are 247 references to alcohol in Scripture. 40 are negative(warnings about drunkenness, potential dangers of alcohol, etc.), 145 are positive (sign of God's blessing, use in worship, etc.), and 62 are neutral(people falsely accused of being drunk, vows of abstinence, etc.) The Bible is anything but silent on the issue of wine. It, like all alcohol, must be treated carefully, seen as a blessing, and received with thanksgiving among those who drink it. It must not be abused.

Was Wine in the Bible Cut with Water?

According to F. S. Fitzsimmonds in his article, “Wine and Strong Drink,” in the New Bible Dictionary, the answer is "no". At least, not in the Old Testament. In the New Testament wine was probably cut with 2 parts water to 1 part wine. Some who oppose the use of wine as a beverage argue that the wine in Scripture was so diluted that it was difficult to become drunk. Scripture itself shows that this is not the case. It appears that the wine in the New Testament, if cut, would have the same alcoholic content as today's beer. (See also, the Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible)

What Should the Christian's Attitude Be Toward Wine?

It's important for Christians to understand the whole picture. Wine is seen as the blessing of God, and as a potential means by which people bring destruction upon themselves.

“These two aspects of wine, its use and its abuse, its benefits and its curse, its acceptance in God’s sight and its abhorrence, are interwoven into the fabric of the OT so that it may gladden the heart of man (Ps. 104:15) or cause his mind to err (Is. 28:7), it can be associated with merriment (Ec. 10:19) or with anger (Is. 5:11), it can be used to uncover the shame of Noah (Gn. 9:21) or in the hands of Melchizedek to honour Abraham (Gn. 14:18).”

Christians should exercise caution with wine and strong drink, practicing moderation and self-control. And toward one another it is important that we allow for liberty without passing judgement for either drinking or abstaining. One can drink to the glory of God, while another can abstain for the glory of God.

What is Wine?

Wine is the gift of God. In it we see the love of God in providing life and joy for all people. But we also see a deeper meaning. In wine we see the love of God in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ which removes our guilt, satisfies God's wrath, and saves all who believe.

Israel is a nation possessing a rich past. The turning pages of history find it at the center of the Bible, while present day finds it at the center of conflict. A country known for many things, wine is not necessarily one of them. Going into a liquor store and requesting the finest bottle of Israeli wine isn’t something many people do.

The reason for this is because wine, until recently, wasn’t something Israel brought to the table, proudly placing a bottle between the rolls and potatoes. Instead, Israeli wine was filled with a reputation for being a type of drink someone should put a cork in. This, however, wasn’t for lack of trying.

Wine production on Israeli lands began thousands of years ago, perhaps even prior to the Biblical era. However, the wines that were made during this time often tasted so bad that bottles shipped to Egypt were garnished with anything that would add flavor. Stopping just short of adding RediWhip, people tossed in everything from honey to berries, from pepper to salt. The bottles sent to Rome, though not lacking flavor, were so thick and so sweet that anyone who didn’t have a sweet tooth, or a spoon, wasn’t able to consume them.

The wine was of such poor quality that when Arab tribes took over Israel in the Moslem Conquest of 636, putting a stop to local wine production for 1,200 years, disappointment didn’t exactly ferment.

In the late 1800’s, wine production began again in Israel. Determined to let Israeli grapes have their day in the sun, a Jewish activist and philanthropist name Baron Edmond de Rothschild began helping Jews flee oppressors, eventually helping them adapt to their Palestine settlements. He then began to help them plant vineyards. Because of this, he is known as a founder of Israel’s wine industry.

But, the kindness and intentions of even the most good-hearted of men wasn’t enough to save Israeli wine from its past reputation. Because the lands of Israel and the climate were not ideal for vine growing, the wine produced was often of poor quality. Too coarse and too sweet to be consumed, Israeli wine was looked on unfavorably until just a few decades ago.

With the adoption of modern equipment, the import of good vine stock, the encouragement given to viticulturists, and the planting of vineyards in mountain ranges, near lakes, and in flat areas, Israel wine has recently become much more appreciated, for its taste and its variety. Replacing the sweet red wines with lighter, dryer red wines and producing more champagne, the wines of Israel have finally begun to climb up the vine in terms of greatness.

The wines presently produced in Israel are done so in one of five regions: Galilee, Shomron, Samson, Negev, and Judean Hills. The Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc are viewed as particularly good, although Israel also produces several Merlots and other common varieties.

Kosher Wine

While not all the wine produced in Israel is Kosher, a good portion of it is. This has led many wine drinkers to have the wrong impression about Israeli wine, an impression that is based on a misconception of what the word “Kosher” truly means.

Some people possess the assumption that when food and drinks are Kosher the taste of the product drastically changes, similar to the way making a hamburger “vegetarian” forever alters its flavor. However, when something is Kosher it simply means that it was made in a way that adheres to the dietary laws of Judaism.

There are two types of Kosher wine: Mevushal and non-Mevushal. For wine to be non-Mevushal, which is the basic form of Kosher, the preparation of it must follow a regime of specific rules. To begin, the equipment used to make wine must be Kosher, and only used for the production of Kosher products. As the wine goes from grape to bottle, it may only be handled, or opened, by Sabbath-observant Jews. During the wine’s processing, only other Kosher products may be used: artificial preservatives and colors, and animal products may not be added.

Wines that are Mevushal are subject to an additional step on the Kosher agenda. Going through flash pasteurization, the wine becomes heated, making it unfit for idolatrous worship. This, in turn, removes some of the restrictions, keeping the wine Kosher no matter who handles it.

Jesus and Wine

The history of Israeli wine is unique in that it also involves the history of Christ. Whether or not Jesus advocated drinking wine, and whether or not the wine he drank was alcoholic, has become a cornerstone in many historical and religious debates. While some people insist that Jesus drank wine, others insist that he didn’t, and, of course, a few Bill Clinton fans insist that he drank, but didn’t inhale.

There are hardly any people arguing on the premise that Jesus consumed large amounts of wine. Instead, people argue whether or not the Bible condemns all use of alcohol or whether it condones its use in moderation. Depending on which side a person prefers to linger, innumerous references from the Bible can go in both directions. Some people assert that the “wine” referenced in the Bible was nothing more than nonalcoholic grape juice. But, those who take an opposing stance state that there are too many Biblical references warning against excessive use of “wine.” If it was just grape juice, or a wine with virtually no alcohol content, there would be no need for precautions.

Though there are several examples of passages in the Bible that involve Jesus drinking wine, with the most famous one likely being The Last Supper, the Bible also includes innumerable references to wine in general, wine drinking that does not necessarily involve Christ.

There are approximately 256 references to wine written in the contents of the Good Book. From these references, readers learn that wine was made from grapes, figs, dates and pomegranates. It was often consumed as part of the every day diet, during times of celebrations, during weddings, as gifts and offerings, and as a symbol of blessing. In some passages, it was even used for medicinal purposes.

Wine Strength During this Era

Another question that often arises in regards to wine in the Bible and Christ’s consumption is its alcoholic strength. If the wine was in fact wine and not grape juice, then it obviously had some sort of alcohol content. However, the wine of the Biblical era was much weaker than the wine we know today. While one reason for this was the addition of water, another reason was naturally fermented wine (wine that does not have additives) was the only wine available during this time. Because sugar and yeast were not yet added to wine, its alcohol content remained lower than modern day spirits.

Whether or not Jesus drank wine, and whether or not it was condoned or condemned, is based on a great deal of speculation. Like many items of debate, people often use passages in the Bible to move an argument in their direction, even when their chosen reference is laden with ambiguity. Some people may swear that he drank, while others may insist that he didn’t. However, in truth, we will probably never know and, along these lines, we really shouldn’t need to: when it comes down to it, a person’s faith is based on much bigger things than their opinion of alcohol.

A Kiddush cup should be able to hold at least a revi'it of liquid. A revi’it is a Talmudic measurement that’s slightly more than 3 liquid ounces. Like many aspects of Jewish practice, there is debate around the exact volume of this measurement. Some opinions say that it is equal to 3.3oz, others place it at 3.8oz, and there are other opinions as well. Regardless of the size of the cup, it is customary to fill it to the brim with wine when reciting Kiddush, as a symbol of the fullness of our blessing and joy.

The person who recites Kiddush drinks a couple sips of the wine (a cheekful or 2oz) and then passes their cup to guests around the table, or pours it into cups for each person. Some families pour the wine for each person individually before reciting Kiddush, or use a Kiddush fountain that doles out wine evenly into small cups.

This is followed by two blessings: One over the wine/grape juice, and one about Shabbat.

סַבְרִי מָרָנָן וְרַבָּנָן וְרַבּותַי:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' אֱלקינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעולָם בּורֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' אֱלקינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעולָם. אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְותָיו וְרָצָה בָנוּ. וְשַׁבַּת קָדְשׁו בְּאַהֲבָה וּבְרָצון הִנְחִילָנוּ. זִכָּרון לְמַעֲשֵׂה בְרֵאשִׁית. (כִּי הוּא יום) תְּחִלָּה לְמִקְרָאֵי קדֶשׁ זֵכֶר לִיצִיאַת מִצְרָיִם. (כִּי בָנוּ בָחַרְתָּ וְאותָנוּ קִדַּשְׁתָּ מִכָּל הָעַמִּים) וְשַׁבַּת קָדְשְׁךָ בְּאַהֲבָה וּבְרָצון הִנְחַלְתָּנוּ: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה' מְקַדֵּשׁ הַשַּׁבָּת:

Blessed are you God, our Lord, King of the Universe, who creates the fruit of the vine.

Blessed are you God, our Lord, King of the Universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments and desired us. And with love and goodwill has invested us with His holy Shabbat, a remembrance of the act of Creation. (For it is) the first of the holy festivals, commemorating the exodus from Egypt. (For You have chosen us and sanctified us, among all the nations) and with love and goodwill You have given us Your Holy Sabbath as an inheritance.

Blessed are You God, who sanctifies the Shabbat.

Judaism has a complicated, double relationship with alcohol — and, in particular, wine. On the one hand, wine, which “cheers the hearts of men” (Psalm 104:15), is a significant component of many Jewish rituals. Kiddush is recited on Shabbat and holidays over a cup of wine. Four cups of wine are integral to the Passover seder. Wine figures prominently in Havdalah, Brit Milah, wedding ceremonies and more. On the other hand, Judaism recognizes the dangers of intoxication which is implicated in some of the worst misdeeds reported in the Hebrew Bible including Noah’sincestual encounter and Nadav and Abihu’s strange fire.

Judaism recognizes that wine brings great joy. The heartsick lover of Song of Songs rhapsodizes:

Draw me after you, let us run! The king has brought me to his chambers. Let us delight and rejoice in your love, savoring it more than wine. — Song of Songs 1:4

This is pretty good billing for a drink! When the spies of the Book of Numbers go to explore the Land of Israel before the Israelites take possession, they discover its many agricultural delights, including cartoonishly enormous, mouth-watering grapes that are so large a single cluster is carried on a pole supported by two men! (Numbers 13:24) This image has inspired many classical pieces of art and the logo of the modern Israeli Ministry of Tourism.

The talmudic rabbis likewise declared wine to be the greatest beverage, not only a delight, but in many instances a religious obligation:

It was taught Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira says: When the Temple is standing, rejoicing is only through the eating of sacrificial meat, as it is stated: “And you shall sacrifice peace-offerings and you shall eat there and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 27:7). And now that the Temple is not standing (and one cannot eat sacrificial meat) he can fulfill the mitzvah of rejoicing on a Festival only by drinking wine, as it is stated: “And wine that gladdens the heart of man” (Psalms 104:15). — Pesachim 109a

In this case, wine replaces the sacrifice and thereby fulfills a religious obligation. The rabbis also prescribe wine for other central Jewish rituals: Kiddush, Havdalah, Passover, and so forth. And it’s not just people — God also appreciates wine! Wine is poured out as a libation offering in the holy Temple.

At the same time, Judaism recognizes critical dangers of over-consumption. One of the most iconic images of prayer in the Hebrew is that of the childless Hannah, pouring her heart out to God as she furiously, restlessly begs for the ability to conceive. Her prayer is so passionate that a priest mistakes her for drunk. She earnestly insists that she is sober.

What is more, Hannah promises God that if she is able to have a child she will dedicate that baby as a Nazarite. Nazarites were a class of Israelites who took upon themselves extra stringent obligations toward God, including abstaining from alcohol. Remaining sober in this way was considered one path to holiness. And, indeed, there is an ascetic strain in Jewish tradition that shuns alcohol.

The Talmud expresses admiration for one who can hold their liquor:

Rabbi Hiyya said: Anyone who remains settled of mind after drinking wine, and does not become intoxicated, has an element of the mind-set of seventy Elders. The allusion is: Wine [yayin spelled yod, yod, nun] was given in seventy letters, as the numerological value of the letters comprising the word is seventy, as yod equals ten and nunequals fifty. Similarly, the word secret [sod spelled samekh, vav, dalet] was given in seventy letters, as samekh equals sixty, vav equals six, and dalet equals four. Typically, when wine entered the body, a secret emerged. Whoever does not reveal secrets when he drinks is clearly blessed with a firm mind, like that of seventy Elders. — Eruvin 65a

Rabbi Hiyya notes that in Gematria, an ancient form of Jewish numerology, the numerical value of the word yayin (“wine”) is seventy. Likewise, the word sod, meaning “secret” has this same value. Seventy was also the number of elders who served on the ancient high court, the Sanhedrin. Rabbi Hiyya teaches that one who can hold his drink and not reveal a secret is like one of those 70 elders.

But for those of us who do succumb to the mind-softening effects of alcohol, wine is a danger. The bumbling King Ahasueros of the Book of Esther is seen mostly drunk, and partly because of this he makes disastrous decisions which nearly lead to the massacre of all the Jews in his kingdom. In the Book of Genesis, Noah becomes drunk and participates in an incestuous tryst (Genesis 9:20-5). And Nadav and Abihu, the high priest Aaron’s sons, become so drunk that they decide to offer “strange fire” to God in the Holy of Holies and pay for the mistake with their lives (Leviticus 10:1). While some wine may “gladden the heart,” too much can make people dangerously reckless — with disastrous consequences.

The following evocative midrash relates the stages of drunkenness:

When a person drinks one cup of wine, he acts like a ewe lamb, humble and meek. When she drinks two, she becomes as mighty as a lion and proceeds to brag extravagantly, saying, ‘Who is like me?’ When he drinks three or four cups, he becomes like a monkey, hopping about, dancing, giggling, and uttering obscenities in public, without realizing what he is doing. Finally, when she becomes blind drunk, she is like a pig; wallowing in mire and coming to rest among refuse.” — Midrash Tanhuma, Noah, 13

Still, wine is a crucial part of Jewish religious observance. Perhaps the double-sided nature of wine is nowhere more explicit than in a rabbinic midrashwhich states that the Tree of Knowledge — the forbidden tree that Adam and Eve sampled, resulting in their expulsion from Eden — was in fact a grape vine. (Sanhedrin 70a) This alluring fruit opens new doors and new paths to awareness — but it is also deadly dangerous.

The juice of the grape is the subject of special praise in the Scriptures. The "vine tree" is distinguished from the other trees in the forest (Ezek. xv. 2). The fig-tree is next in rank to the vine (Deut. viii. 8), though as food the fig is of greater importance (comp. Num. xx. 5) than the "wine which cheereth God and man" (Judges ix. 13; comp. Ps. civ. 15; Eccl. x. 19). Wine is a good stimulant for "such as be faint in the wilderness" (II Sam. xvi. 2), and for "those that be of heavy hearts" (Prov. xxxi. 6).

The goodness of wine is reflected in the figure in which Israel is likened to a vine brought from Egypt and planted in the Holy Land, where it took deep root, spread out, and prospered (Ps. lxxx. 9-11). The blessed wife is like "a fruitful vine by the sides of thy house" (Ps. cxxviii. 3). When peace reigns every man rests "under his vine and under his fig-tree" (I Kings v. 5 [A. V. iv. 25]). An abundance of wine indicates prosperity. Jacob blessed Judah that "he washed his garments in wine and his clothes in the blood of grapes" (Gen. xlix. 11).

Bread as an indispensable food and wine as a luxury represent two extremes; they were used as signs of welcome and good-will to Abraham (Gen. xiv. 18). A libation of wine was part of the ceremonial sacrifices, varying in quantity from one-half to one-fourth of a hin measure (Num. xxviii. 14).

Wine-drinking was generally accompanied by singing (Isa. xxiv. 9). A regular wine-room ("bet ha-yayin") was used (Cant. ii. 4), and wine-cellars ("oẓerot yayin"; I Chron. xxvii. 27) are mentioned. The wine was bottled in vessels termed "nebel" and "nod" (I Sam. i. 24, xvi. 20), made in various shapes from the skins of goats and sheep, and was sold in bath measures. The wine was drunk from a "mizraḳ," or "gabia'" (bowl; Jer. xxxv. 5), or a "kos" (cup). The wine-press was called "gat" and "purah"; while the "yeḳeb" was probably the vat into which the wine flowed from the press. The "vine of Sodom" (Deut. xxxii. 32), which probably grew by the Dead Sea, was the poorest kind. The "vine of the fields" (II Kings iv. 39) was a wild, uncultivated sort, and the "soreḳ" (Isa. v. 2) was the choicest vine, producing dark-colored grapes; in Arabic it is called "suriḳ."

There were different kinds of wine. "Yayin" was the ordinary matured, fermented wine, "tirosh" was a new wine, and "shekar" was an old, powerful wine ("strong drink"). The red wine was the better and stronger (Ps. lxxv. 9 [A. V. 8]; Prov. xxiii. 31). Perhaps the wine of Helbon (Ezek. xxvii. 18) and the wine of Lebanon (Hos. xiv. 7) were white wines. The vines of Hebron were noted for their large clustersof grapes (Num. xiii. 23). Samaria was the center of vineyards (Jer. xxxi. 5; Micah i. 6), and the Ephraimites were heavy wine-drinkers (Isa. xxviii. 1). There were also "yayin ha-reḳaḥ" (spiced wine; Cant. viii. 2), "ashishah" (hardened sirup of grapes), "shemarim (wine-dregs), and "ḥomeẓ yayin" (vinegar). Some wines were mixed with poisonous substances ("yayin tar'elah"; Ps. lx. 5; comp. lxxv.9, "mesek" [mixture]). The "wine of the condemned" ("yen 'anushim") is wine paid as a forfeit (Amos ii. 8), and "wine of violence" (Prov. iv. 17) is wine obtained by illegal means.

Wine is called "yayin" because it brings lamentation and wailing ("yelalah" and "wai") into the world, and "tirosh" because one that drinks it habitually is certain to become poor (). R. Kahana said the latter term is written sometimes

, and sometimes

; that means, if drunk in moderation it gives leadership (

= "head"); if drunk in excess it leads to poverty (Yoma 76b). "Tirosh" includes all kinds of sweet juices and must, and does not include fermented wine (Tosef., Ned. iv. 3). "Yayin" is to be distinguished from "shekar"; the former is diluted with water ("mazug"); the latter is undiluted ("yayin ḥai"; Num. R. x. 8; comp. Sifre,Num. 23). In Talmudic usage "shekar" means "mead," or "beer," and according to R. Papa, it denotes drinking to satiety and intoxication (Suk. 49b).

In metaphorical usage, wine represents the essence of goodness. The Torah, Jerusalem, Israel, the Messiah, the righteous—all are compared to wine. The wicked are likened unto vinegar, and the good man who turns to wickedness is compared to sour wine. Eleazar b. Simeon was called "Vinegar, the son of Wine" (B. M. 83b). The wine which is kept for the righteous in the world to come has been preserved in the grape ever since the six days of creation (Ber. 34b).

The process of making wine began with gathering the grapes into a vat ("gat"). There were vats hewn out of stone, cemented or potter-made vats, and wooden vats ("Ab. Zarah v. 11). Next to the vat was a cistern ("bor"), into which the juice ran through a connecting trough or pipe ("ẓinnor"). Two vats were sometimes connected with one cistern (B. Ḳ. ii. 2). The building containing or adjoining the wine-presses was called "bet ha-gat" (Tosef., Ter. iii. 7). The newly pressed wine was strained through a filter, sometimes in the shape of a funnel ("meshammeret"; Yer. Ter. viii. 3), or through a linen cloth ("sudar"), in order to remove husks, stalks, etc. A wooden roller or beam, fixed into a socket in the wall, was lowered to press the grapes down into the vat (Shab. i. 9; Ṭoh. x. 8).

The cistern was emptied by a ladle or dipper called the "maḥaẓ" (Ṭoh. x. 7), the wine being transferred to large receptacles known variously as "kad," "ḳanḳan," "garab," "danna," and "ḥabit." Two styles of ḥabit, the Lydian and the Bethlehemite (Niddah vi. 6), were used, the former being a smaller barrel or cask. All these receptacles were rounded earthen vessels, tightly sealed with pitch. The foster-mother of Abaye is authority for the statement that a six-measure cask properly sealed is worth more than an eight-measure cask that is not sealed (B. ḳ. 12a). New wine stood for at least forty days before it was admissible as a drink-offering ('Eduy. vi. 1; B. B. 97a). When the wine had sufficiently settled it was drawn off into bottles known as "lagin" or "leginah" and "ẓarẓur," the latter being a stone vessel with a rim and strainer, a kind of cooler (Sanh. 106a); an earthen pitcher, "ḥaẓab," was also used (Men. viii. 7). The drinking-vessel was the Biblical "kos." The wine was kept in cellars, and from them was removed to storerooms called "hefteḳ," or "apoṭiḳ" (ἀποθήκη), a pantry or shelves in the wineshop. Bottles of wine from this pantry were exposed for sale in baskets in front of the counter ('Ab. Zarah ii. 7, 39b).

The quality of a wine was known by its color and by the locality from which it came, red wine being better than white wine. Ḳeruḥim (probably the Coreæ of Josephus) in Palestine produced the best wine (Men. viii. 6), after which came the red wine of Phrygia (Perugita;Shab. 147b), the light-red wine of Sharon (Shab. 77a), and "yayin Kushi" (Ethiopian wine; B. B. 97b). There were special mixtures of wine. Among these were: (1) "alunṭit," made of old wine, with a mixture of very clear water and balsam; used especially after bathing (Tosef., Dem. i. 24; 'Ab. Zarah 30a); (2) "ḳafrisin" (caper-wine, or, according to Rashi, Cyprus wine), an ingredient of the sacred incense (Ker. 6a); (3) "yen ẓimmuḳin" (raisin-wine); (4) "inomilin" (οἰνόμελι), wine mixed with honey and pepper (Shab. xx. 2; 'Ab. Zarah l.c.); (5) "ilyoston" (*ήλιόστεον), a sweet wine ("vinum dulce") from grapes dried in the sun for three days, and then gathered and trodden in the midday heat (Men. viii. 6; B. B. 97b); (6) "me'ushshan," from the juice of smoked or fumigated sweet grapes (Men. l.c.); not fit for libation; (7) "enogeron" (οινόγαρον), a sauce of oil and garum to which wine was added; (8) "apiḳṭewizin" (ἀποκοτταβίζειν), a wine emetic, taken before a meal (Shab. 12a); (9) "ḳundiṭon" ("conditum"), a spiced wine ('Ab. Zarah ii. 3); (10) "pesintiṭon" ("absinthiatum"), a bitter wine (Yer. 'Ab. Zarah ii. 3); (11) "yen tappuḥim," made from apples; cider; (12) "yen temarim," date-wine. Wine made from grapes grown on isolated vines ("roglit") is distinguished from that made of the grapes of a vine suspended from branches or trained over an espalier ("dalit"); the latter was unfit for libation (Men. 86b).

During the time of fermentation the wine that was affected with sourness was called "yayin ḳoses" (Yer. Pe'ah ii., end), and when matured sour it was "ḥomeẓ" (vinegar). Good vinegar was made by putting barley in the wine. In former times Judean wine never became sour unless barley was put in it; but after the destruction of the Temple that characteristic passed to the Edomite (Roman) wine. Certain vinegar was called the "Edomite vinegar" (Pes. 42b).

Fresh wine before fermenting was called "yayin mi-gat" (wine of the vat;Sanh. 70a). The ordinary wine was of the current vintage. The vintage of the previous year was called "yayin yashan" (old wine). The third year's vintage was "yayin meyushshan" (very old wine). Ordinary, fermented wine, accordingto Raba, must be strong enough to take one-third water, otherwise it is not to be regarded as wine (Shab. 77a). R. Joseph, who was blind, could tell by taste whether a wine was up to the standard of Raba ('Er. 54a).

Wine taken in moderation was considered a healthful stimulant, possessing many curative elements. The Jewish sages were wont to say, "Wine is the greatest of all medicines; where wine is lacking, there drugs are necessary" (B. B. 58b). R. Huna said, "Wine helps to open the heart to reasoning" (B. B. 12b). R. Papa thought that when one could substitute beer for wine, it should be done for the sake of economy. But his view is opposed on the ground that the preservation of one's health is paramount to considerations of economy (Shab. 140b). Three things, wine, white bread, and fat meat, reduce the feces, lend erectness to one's bearing, and strengthen the sight. Very old wine benefits the whole body (Pes. 42b). Ordinary wine is harmful to the intestines, but old wine is beneficial (Ber. 51a). Rabbi was cured of a severe disorder of the bowels by drinking apple-wine seventy years old, a Gentile having stored away 300 casks of it ('Ab. Zarah 40b). "The good things of Egypt" (Gen. xlv. 23) which Joseph sent to his father are supposed by R. Eleazar to have included "old wine," which satisfies the elderly person (Meg. 16b). At the great banquet given by King Ahasuerus the wine put before each guest was from the province whence he came and of the vintage of the year of his birth (Meg. 12a). Until the age of forty liberal eating is beneficial; but after forty it is better to drink more and eat less (Shab. 152a). R. Papa said wine is more nourishing when taken in large mouthfuls. Raba advised students who were provided with little wine to take it in liberal drafts (Suk. 49b) in order to secure the greatest possible benefit from it. Wine gives an appetite, cheers the body, and satisfies the stomach (Ber. 35b). After bleeding, according to Rab, a substantial meal of meat is necessary; according to Samuel, wine should be taken freely, in order that the red of the wine may replace the red of the blood that has been lost (Shab. 129a).

The benefit derived from wine depends upon its being drunk in moderation, as overindulgence is injurious. Abba Saul, who was a grave-digger, made careful observations upon bones, and found that the bones of those who had drunk natural (unmixed) wine were "scorched"; of those who had used mixed wine were dry and transparent; of those who had taken wine in moderation were "oiled," that is, they had retained the marrow (Niddah 24b). Some of the rabbis were light drinkers. R. Joseph and Mar 'Uḳba, after bathing, were given cups of inomilin wine (see above). R. Joseph felt it going through his body from the top of his head to his toes, and feared another cup would endanger his life; yet Mar 'Uḳba drank it every day and was not unpleasantly affected by it, having taken it habitually (Shab. 140a). R. Judah did not take wine, except at religious ceremonies, such as "Ḳiddush," "Habdalah," and the Seder of Passover (four cups). The Seder wine affected him so seriously that he was compelled to keep his head swathed till the following feast-day—Pentecost (Ned. 49b).

The best remedy for drunkenness is sleep. "Wine is strong, but sleep breaks its force" (B. B. 10a). Walking throws off the fumes of wine, the necessary amount of exercise being in the proportion of about three miles to a quarter-measure of Italian wine ('Er. 64b). Rubbing the palms and knees with oil and salt was a measure favored by some scholars who had indulged overmuch (Shab. 66b).

For religious ceremonies wine is preferable to other beverages. Wine "cheereth God" (Judges ix. 13); hence no religious ceremony should be performed with other beverages than wine (Ber. 35a). Over all fruit the benediction used is that for "the fruits of the tree," but over wine a special benediction for "the fruits of the vine" is pronounced (Ber. vi. 1). This latter benediction is, according to R. Eliezer, pronounced only when the wine has been properly mixed with water. Over natural wine the benediction is the same as that used for the "fruits of the tree" (Ber. 50b). The drinking of natural wine on the night of Passover is not "in the manner of free men" (Pes. 108b). "Ḳiddush" and "Habdalah" should be recited over a cup of wine. Beer may be used in countries where that is the national beverage (Pes. 106a, 107a). According to Raba, one may squeeze the juice of a bunch of grapes into a cup and say the "Ḳiddush" (B. B. 97b). The cup is filled with natural wine during grace, in memory of the Holy Land, where the best wine is produced; but after grace the wine is mixed.

The words introducing the grace, "Let us praise Him whose food we have eaten, and by whose goodness we live," are said over a cup of wine, part of which is passed to the hostess (Ber. 50a). Ulla, when the guest of R. Naḥman, was invited to pronounce the grace over wine, and the latter suggested the propriety of sending part of the wine to his guest's wife, Yalta; but Ulla demurred, declaring that the host is the principal channel of blessing, and passed it to R. Naḥman. When Yalta heard this she was enraged, and expressed her indignation by going to the wine-room ("be ḥamra") and breaking up 400 casks of wine (Ber. 51b). R. Akiba, when he made a feast in honor of his son, proposed, "Wine and long life to the Rabbis and their disciples!" (Shab. 67b).

Following the Scriptural precept, "Give strong drink unto him that is ready to perish, and wine unto those that be of heavy hearts" (Prov. xxxi. 6), the Rabbis ordered ten cups of wine to be served with the "meal of consolation" at the mourner's house: three cups before the meal, "to open the bowels," three cups between courses, to help digestion, and four cups after the grace. Later four cups were added in honor of the ḥazzanim, the parnasim, the Temple, and the nasi Gamaliel. So many cups producing drunkenness, the last four were afterward discontinued (Ket. 8b). Apparently this custom was in force when the Temple was in existence, and persisted in Talmudic times; it disappeared in the geonic period. R. Ḥanan declared that wine was created for the sole purpose of consoling the bereaved and rewarding the wicked forwhatever good they may do in this world, in order that they may have no claim upon the world to come (Sanh. 70a). After the destruction of the Temple many Pharisees, as a sign of mourning, vowed to abstain from eating meat and drinking wine, but were dissuaded from issuing a decree which the public could not observe (B. B. 60b). R. Judah b. Bathyra said, "Meat was the principal accompaniment of joy in the time of the Temple, wine in post-exilic times" (Pes. 109a).

Rab said that for three days after purchase the seller is responsible if the wine turns sour; but after that his responsibility ceases. R. Samuel declared that responsibility falls upon the purchaser immediately upon the delivery of the wine, the rule being "Wine rests on the owner's shoulders." R. Ḥiyya b. Joseph said, "Wine must share the owner's luck" (B. B. 96a, b, 98a). If one sells a cellarful of wine, the purchaser must accept ten casks of sour wine in every hundred (Tosef., B. B. vi. 6). Whoever sells spiced wine is responsible for sourness until the following Pentecost (i.e., until the hot weather sets in). If he sells "old wine," it must be of the second year's vintage; if "very old wine" ("meyushshan"), it must be of the third year's vintage (B. B. vi. 2).

The question of responsibility on the part of carriers of wine ("sheḳulai") is discussed. When Rabbah bar Ḥana's hired carriers broke a cask he seized their overgarments; thereupon the carriers appealed to Rab, who ordered Rabbah to return their garments. "Is this the law?" asked Rabbah in astonishment. "It is the moral law," answered Rab, citing, "That thou mayest walk in the way of good men" (Prov. ii. 20). When the garments had been returned the carriers appealed again: "We are poor men; we have worked all day; and now we are hungry, and have nothing." Rab then ordered Rabbah to pay them their wages. "Is this the law?" inquired Rabbah. "It is the higher law," replied Rab, completing the verse previously cited—"and keep the paths of the righteous" (B. M. 83a).

As a commodity, wine has an important place in the business world. A large proportion of the trade in wine for the Feast of Passover is controlled by Jews. The agricultural activity of Palestine is directed mainly to viticulture. The Rothschild cellars at Rishon le-Ẓiyyon receive almost the entire produce of the Jewish colonists, which, through the Carmel Wine Company, is distributed throughout Russia, Austria, Holland, Switzerland, France, England, and the United States. The vintage of 1904 in the Rothschild cellars exceeded 7,000,000 bottles, of which 200,000 were sold in Warsaw. See Agricultural Colonies in Palestine.

Regarding the interdiction of wine prepared or handled by Gentiles see Nesek.

- C. H. Fowler, The Wine of the Bible, New York, 1878;

- W. Ebstein, Die Medizin im Neuen Testament und im Talmud, i. 36, 167; ii. 250, Stuttgart, 1903.

The strict prohibition against the use of gentile wine during the talmudic period, originally limited to used in idolatrous libations but later extended to include all non-Jewish wine (Av. Zar. 2:3, and 36b), must of necessity have concentrated the wine trade in the hands of Jews. Apart from this, however, there is no evidence of any specific Jewish aspect to the wine trade during this period. There are references to Jewish keepers of wine taverns ().

A certain difference may be detected between and . Whereas in the former, a Mediterranean country, Jews drank wine in preference to other alcoholic beverages, in Babylonia the brewing of beer and other alcoholic beverages was much more common. Some of the Babylonian were brewers, among them R. Papa, who was regarded as an expert and amassed a considerable fortune from it (; BM65a). However, the vine was cultivated in the neighborhood of Sura and Jews were engaged in the manufacture and sale of wine ().

Middle Ages (to 16thCentury)

As a result of both the historio-economic and the religious factors, during the Middle Ages viticulture was one of the branches of agriculture in which Jews had traditional interest and technical proficiency. The rabbinical responsa and takkanotprovide ample instances of the endeavors made by Jews to obtain supplies of suitably pure wine and the arrangements made for doing so. This was perhaps one of the main reasons why the Jews continued to engage in viticulture longer than in other types of agriculture in this period, though from the 11th century the sources mention that Jews in Western Europe also drank mead.

In several areas, Jewish winegrowers or vintners also sold wine to . In the region of , the teacher of (b. 1050) used to sell “from his barrel to the gentile” (Rashi, Resp., no. 159). The Jews of Speyer and Worms were licensed by the emperor in 1090 “to sell their wine to Christians” (Aronius, Regesten, nos. 170–1).

The antagonisms created by the sale of a product to which Jews and Christians attached divergent sacral usages and regulations are reflected in complaints such as that “on the insolence of the Jews” by archbishop Agobard of , who wrote (c. 825): “As to wine which even they themselves consider unclean and use only for sale to Christians – if it should happen that some of it is spilt on the earth, even in a dirty place, they hasten to collect it and return it for keeping in jars.”

The problem is even more strongly presented by Pope in his letter of January 1208: “At the vintage season the Jew, shod in linen boots, treads the wine; and having extracted the purer wine in accordance with the Jewish rite they retain some for their own pleasure, and the rest, the part which is abominable to them, they leave to the faithful Christians; and with this, now and again, the sacrament of the blood of Christ is performed.” The description may apply either to Jewish vintners and vineyard owners or to Jews who made arrangements with Christian owners to permit the Jews to extract pure wine in accordance with Jewish law.

In the the Jewish wine trade assumed considerable proportions, as indicated by examples from 12th-century . It is reported in 1136 that “four partners [all Jews] joined in the production of wine with the enormous sum of 1,510 dinars”; upon liquidating the partnership and paying their taxes, all expressed their satisfaction (S.D. Goitein, Mediterranean Society(1967), 364). In about 1150, a Jewish estate included 1,937 jars of wine, worth about 200–300 dinars (ibid., 264). The amounts cited indicate that such thriving business had customers besides Jews and Christians.

In , in the 12th and 13thcenturies, Jews imported wine, and “were exempt from paying any custom or toll or any due on wine, in just the same way as the king himself, whose chattels they were” (Roth, England, 102–3; cf. also 115, note). In Central Europe, Jewish drinking habits were already gradually changing in the 13th century, as shown by the man who asked R. Meir b. Baruch of Rothenburg for his opinion “about beer [i.e., whether this might be used for ], for in his locality there is sometimes a lack of wine.” R. Meir answered: “There is no wine in , but in all [other] principalities there is abundant wine; and there is wine in your city throughout the year. It seems to me that you personally drink mostly wine; and if at the end of the year there is some dearth of wine you will find it in your neighborhood…. Certainly you know that it is proper to recite Kiddush over wine” (Meir b. Baruch of Rothenburg, Resp., ed. by Y.Z. Kahana, vol. 1, nos. 72, 80).

While by the 15th century Jews must have practically ceased to own vineyards and practice viticulture, trade in wine and other alcoholic beverages was becoming a major Jewish occupation in the German and west Slavic lands. This was part of the general trend of increasing commerce between town and country in this period in which Jews took an active part, not least because they were expelled from the larger cities (see ). The competition of the Jewish vintner was an object of complaints by the guilds, such as that of in 1516 (cf. R. Straus, Urkunden und Aktenstuecke zur Geschichte der Juden in Regensburg (1960), 291, no. 833). In part, this commerce was combined with credit extension, as explained by Jews in Regensburg in 1518, who lent money to the boatmen carrying wine to the city and were sometimes repaid in kind (ibid., 358, no. 988).

In both Muslim and Christian , the sale and consumption of wine in the Middle Ages were subject to taxation by the autonomous Jewish communal administration. The unbroken records give evidence of the significant scale on which Spanish Jewry engaged in business. Copious wine drinking by the upper Jewish social strata is also frequently mentioned in Jewish in Spain. After 1391, exiles from Spain carried their wine trade to Islamic countries, and occasionally aroused opposition from their hosts. These traditions and trends were in part continued, in part considerably modified, in the course of the 16thand 17th centuries.

[Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson]

16th Century to Modern Times

From the 16th to the 19thcenturies the production and sale of alcoholic beverages was a major industry in - and . It also occupied an important place in the economy of , Silesia, , and . As essentially connected with agriculture, it was carried out in rural estates and formed one of the main sources of revenue for their proprietors. The Jews entered this industry under the (“rental”) system in the rural economy in which by the 16th century they played an essential role. The Jewish tavern keeper became part of the regular socioeconomic pattern of life in the town and village. The association of the Jew with this activity contributed another negative feature to the popularly created image of the Jew while also affecting Jewish living habits and standards. The alcoholic beverage industry afforded to the Jews a variety of occupations and a source of livelihood enabling them to raise their living standards.

In almost all the rural estates in Poland, the owners held the monopoly over the production and sale of alcoholic beverages, and the heavy drinking habits of the peasants in these countries made it a highly lucrative prerogative. The participation of Jews took the form of leasing in one of the following ways: The lease of breweries, distilleries, and taverns which was part of the wider arenda system in Poland and in Ukrainian and Belorussian territories: often, the lease of breweries and distilleries, together with taverns, formed a separate concession; the basic leasehold concession of the single tavern, which was rented either directly from the noble estate owner or from a larger-scale Jewish leaseholder. All leases were granted for a limited term, often for three years, sometimes for one year only. Jewish communal regulations (takkanot) effectively limited competition between Jews in bidding for the leases at least to the end of the 17th century (see ). Tavern keepers were the largest group of Jews occupied in the industry. They frequently belonged to the poorer class of Jew who had contact with the peasants.

The industry also accounted for an appreciable number of brewers and distillers who worked for the brewery or distillery leaseholders as employees. They were sometimes also employed by taverners. In the middle of the 17th century, this group represented about 30% of the Jews engaged in the production and sale of alcoholic beverages on Polish territory. On the crownestates, the income from the production and sale of alcoholic beverages amounted to 0.3% of the total revenues in 1564, and to about 40% in 1789, an immense increase directly connected with the participation of the Jews in this industry.

Jews also played a similar role in the towns. The location privileges accorded to townships in Eastern Europe usually granted the municipality the right to lease production and sale of alcoholic beverages in the town to an individual local resident. Jews also often competed with other townsmen for this concession, and were generally more ready to supply credit than their Christian competitors. In 1600 the magistrate of complained: “The Jews are not permitted to keep taverns, and yet they deal openly in the sale of vodka, wine, and mead; they hire musicians to tempt in people” (M. Balaban, Dzieje ?ydów w Krakowie i na Kazimierzu, 1 (1931), 197). Jewish sources confirm the nature of the competition that took place in the cities. The communal regulations for the district of of about 1602 enjoin that:

In in about 1648, 17 taverns were owned by Jews, although the Jewish population consisted of only 100 families. In towns in Poland and Lithuania where the monopoly was held by the city, it was also leased to Jews. The municipal prerogative was usurped by the manorial owners of the towns during the 17thcentury, and the concessions for production and sale of alcoholic beverages were leased to Jews on an increasing scale. In the old crown cities, Jews also often leased the tavern from the city authority.

In the second half of the 16th and the first half of the 17th century, a considerable number of Jewish distillers, brewers, and taverners were thus occupied on the estates of the magnates situated in the Belorussian and Ukrainian territories under Poland. Ruin came in 1648–51, following the uprising.

After the truce was concluded between Poland and Russia in 1667, Jewish taverners could again settle in the in the region on the right bank of the River Dnieper; the lands on the left bank passed to Russia, from which Jews were excluded. Jewish taverners were not therefore found in the latter area until the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century.

The proportion of Jews gainfully engaged in the production and sale of alcoholic beverages amounted in 1765 to 15% of the Jewish residents in the towns, and at the period of the partitions of Poland-Lithuania (1772–95) to about 85% of Jewish residents in rural areas. In 1791, it was estimated that if the Jews were to be debarred from leasing taverns, about 50,000 people would have to replace them in this occupation, and this was used as an argument against the Russian authorities when they wished to exclude the Jews, in territories then annexed to Russia, from this source of livelihood.

In the period before 1648, Jewish participation in the liquor trade as taverners gave rise to social tensions, which are reflected in contemporary Jewish works and communal regulations, while furnishing a source for anti-Jewish accusations and conflicts between the peasants and Jewish taverners. Antisemites ascribed the drunkenness prevalent among the peasants, and their permanent state of indebtedness, to the wily Jewish taverner, who also extended credit to them.

During the 17th and 18thcenturies, there were uprisings against Jewish leaseholders on numerous estates in Poland, and the complaints of the peasants on the crown estates were often taken up by the courts. After 1648, as opportunities for employment narrowed with the progressive deterioration in Poland of the economy and culture, the hostility intensified and conditions became more difficult for the Jews, in particular for the keeper of the single tavern. He was at the mercy of the despotic noble who ruled the village. In his autobiography recalls vivid childhood memories of the tribulations of a Jewish leaseholder in the 18th century.

Toward the end of the 18thcentury, in particular after the massacres of 1768, spokesmen of Polish mercantilist and physiocratic theories represented the presence of Jews in the villages and taverns as highly detrimental to Polish economy and society. With few exceptions, the opinion prevailed that the Jewish leaseholders were responsible for the deterioration of the towns and the misery of the countryside. To gain control of these concessions was of greatest importance to the impoverished Polish towns, as the production and sale of alcoholic beverages was a principal branch of the urban economy and its principal source of revenue. Elimination of Jews from this occupation became, therefore, one of the main slogans of the All-Polish middle-class movement between 1788 and 1892.

The Polish Sejm (“diet”) had passed a bill in 1776 establishing the prior right of the citizen to the lease of the production and sale of alcoholic beverages in smaller towns. However, few candidates with the necessary capital could be found, and these soon had to give it up. As a result, in these towns also the lease passed to Jews. In 1783, an order was issued in Belorussia debarring Jews from traffic in alcoholic beverages in the towns, and the income from taverns was given to the municipalities; but this was canceled in 1785.

Following the partitions of Poland-Lithuania, the Jews in the taverns and villages became the scapegoats of the Russian and Polish ruling classes for the poverty and wretchedness of the peasants. These classes were closely bound by social interests and class consciousness, although divided by national and religious enmities. In the large tracts now occupied by Russia the peasants were of the Greek Orthodox faith, and although despised socially, were now the concern of the Russian authorities. The allegation against the Jew as “the scourge of the village,” intoxicating the ignorant peasant because of the misery of his lot, became a spurious slogan for social reform for both the rulers of Russia and their Polish opponents. Elimination of Jewish taverners had started even before the partitions of Poland, and subsequently proceeded with the approval of the Russian governors.

The other states which had gained Polish territory also took up this policy, although with less concentration. The Patent of Tolerance issued by the Austrian emperor in 1782 ordered all the owners of estates to discharge Jewish leaseholders from their domains within two years. This decision was, however, not carried out.

About 1805, the Prussian authorities prepared a ban against leasing taverns to Jews, but owing to the occupation of the country by , it was never put into effect. In 1804, Russian legislation prohibited Jews from living in the villages. In the period of Napoleon’s ascendancy, the Russian authorities refrained from taking action and, in 1812, the orders were suspended. However, after 1830, the stereotype of Jewish guilt for the drunkenness of the peasants was widely propagated in the Polish press. Steps were taken for supervision of the Jews in the name of benefiting the peasant.

In Bessarabia, the participation of Jews in the production and sale of alcoholic beverages was limited in 1818. Legislation passed in Russia in 1835 prohibited the Jews from selling alcoholic beverages on credit to the peasants, and canceled all the peasants’ debts to Jewish taverners. A law of 1866 permitted Jews to lease breweries and distilleries only in towns and villages inhabited by Jews. These measures had little result.

In Belorussia between 1883 and 1888, 31.6% of the distilleries in the province of Vitebsk and 76.3% in that of Grodno were Jewish-owned. Full rights to produce and trade in alcoholic beverages in Russia had been permitted to Jews belonging to the category of “merchants of the first class,” but after 1882 restrictions were also applied against them.

The part played by Jews in the liquor industry continued to concern the Russian government well into the 20th century, even though assuming other forms. The emancipation of the peasants, cancellation of the compulsory quota of consumption, and abrogation of the monopoly of the estate owners changed the economic character and social aspects of the problem. In independent Poland between the two world wars, various economic and legal measures were taken to drive the Jews from this branch, including regulations for hygiene and manipulation of the state monopoly on the sale of vodka. The development of capitalist industry and trade in the second half of the 19th century and freer access to Jews to take up crafts, enabled many Jews in Eastern Europe to enter other branches of the economy. Even so, the image of the Jew invoked by antisemites in Eastern Europe still made frequent use of the hated Jewish taverner.

The feelings of loathing with which the Jew regarded his place behind the tavern counter is powerfully expressed by the poet . The taverner and his family saw themselves placed at the:

[Jacob Goldberg]

In North America

In addition to the prohibition against partaking of non-Jewish wine, its ceremonial use for various occasions, such as Kiddushand on all festive occasions, as well as the need for all wine and liquors to be kasher for , observances both practiced even by those who were not particular with regard to non-Jewish wine for ordinary use, resulted in a specific Jewish trade in wine (and for Passover in other liquors) for specific Jewish consumption in all countries. The needs of the Jewish population were met by local manufacturers especially where wine could not be imported from Eretz Israel.

U.S. Jews tended to make their wine personally or in small shops. The 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Volstead Act, which prohibited the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages, made an exception in favor of such beverages when needed for religious purposes. Abuses of this privilege by some Jews to supply the illegal liquor market disturbed U.S. Jewry. They led to the issuance of a controversial responsum by the talmudic scholar Louis Ginzberg, Teshuvah al Devar Yeinot, etc., permitting grape juice to be used for religious purposes instead of wine.

Following the end of Prohibition in 1933, the business of several Jewish wine manufacturers reached national proportions, supplying the non-Jewish as well as the Jewish market. In the U.S. few Jews were tavern keepers. However, they were prominent among distillers and retailers. Such families as Bernheim, Lilienthal, and Publicker were important distillers, and the general prominence of Jews as retail merchants included the selling of bottled liquor.

Some Jewish firms grew to considerable proportions in Europe as well as the U.S. Many expanded their activity to include general trade in wine and liquors and this may be the origin of the extensive representation of Jews in the English public house trade, for example, the firm of Levy and Franks.

Sedgewick’s, owned by the family of Canada, became one of the largest distilleries in the world.

Wine Industry In Eretz Israel

In Eretz Israel a few small winepresses were owned by Jews, mainly in the of and in other ancient cities inhabited by Jews, before the beginning of modern Jewish settlement in the second half of the 19th century. These were simple household wine-presses, catering chiefly to local consumption. The raw material was supplied by Arab vineyards in the surrounding hill regions.

The first vines of European variety were planted at the agricultural school founded in 1870. The school also built the first European-style wine cellar, which is still in use. With the beginning of modern Jewish settlement, the first vineyards were planted at and later in other moshavot. , who sponsored early Jewish pioneer settlement in Eretz Israel, had high hopes that viticulture would develop as one of the main economic bases for the Jewish villages. He invited specialists from abroad, who selected high-grade varieties in order to produce quality wines. After the harvest of the first crops, he built large wine cellars at Rishon le-Zion (1889) for , and at (1892) for Samaria. These cellars were equipped with refrigerators to retard fermentation and thereby improve quality.

The Baron paid high prices for the grapes in order to assure the settlers a decent standard of living. Economic prosperity resulted in a rapid development of viticulture, and, at the end of the century, vineyards covered about half of the total Jewish land under cultivation. In the course of time, millions of francs were paid to maintain high wine prices, and many settlers concentrated on making wine as their sole occupation. A large overstock of wine accumulated, and wine surpluses continued to increase until a crisis was reached. It was decided to uproot one-third of the vineyards in order to reduce the size of the crop and maintain prices. The winegrowers were compensated by the Baron, and, instead of vineyards, planted almond trees, olives, and the first citrus groves. In 1890–91, the vineyards in Samaria and Galilee were attacked by phylloxera, which ruined the plantations. The infected vines had to be uprooted and replaced by pest-resistant plants brought from India.

In 1906, the management of the wine cellars at Rishon le-Zion and Zikhron Ya’akov was handed over to the farmers, who founded the Carmel Wine Growers Cooperative. At the same time, several private wine cellars, such as Ha-Tikvah and Na?alat ?evi were established. Their wine was sold both locally and abroad.

During , the local wine found a greatly increased market among the German, British, and Australian troops passing through the country. After the war, however, the Eretz Israel wine industry lost its principal markets: Russia, because of the Revolution; the United States, because of Prohibition; and Egypt and the Middle East, because of Arab nationalism. The industry had to undergo a period of adaptation. The acreage under grapes was reduced, chiefly in Judea, where vineyards were replaced by citrus groves. On the other hand, additional areas were planted, mainly in the Zikhron Ya’akov area. During , new plantations were developed on a smaller scale, and with the establishment of the State of Israel (1948), the wine-growing areas covered about 2,500 acres (10,000 dunams). At that time there were 14 wine cellars in Israel.

Large new areas were planted in the , the Jerusalem area, , and Galilee – some of which had never previously been considered suitable for wine growing. With successive waves of immigrants, drinking habits have changed. During the earlier period 70%–75% of the wine consumed was sweet, but later, two-thirds of the total consumption was dry wine.

The Israel Wine Institute, established in cooperation with the industry and the government, undertakes research for the improvement of wine production in Israel. Preference is given to wine plantations in the hilly regions. Varieties of better quality are selected, and new varieties are introduced. Israel wine is exported to many countries of the world. It is widely in demand among Jews for ritual purposes but efforts have been made to broaden the market.

[Nathan Hochberg]

The Israeli wine industry underwent a revolution starting in the 1970s and now numbers hundreds of wineries, ranging from leaders like Golan Heights, Carmel, and Barkan Wine Cellars to boutique wineries like the prize-winning Domaine du Castel in the Judean Hills. Israeli wines are now served in quality restaurants in 40 countries. Around 7,500 acres of vineyards produce about 50,000 tons of grapes a year

The upcoming binge (falling on Saturday and Sunday) is a spiritual practice rooted in the Hebrew Scriptures’ Book of Esther.

According to the narrative, the evil prime minister Haman plots to exterminate Jews who were living throughout the Persian Empire. But Queen Esther, a Jew, saves the day by pleading with King Xerxes to spare her people and to hang Haman.

To commemorate their victory over their enemies, religious Jews observe Purim each year.

Wine flows freely throughout the Book of Esther.

The Hebrew text indicates they drank wine until they didn’t know any better, said Rabbi Yosil Rosenzweig, spiritual leader of Beth Jacob (Orthodox) Congregation in Kitchener.

“So we have a custom of drinking so that we can’t tell the difference between … the hero and … the villain.”

Some Jews take the custom more seriously than others, Rosenzweig noted.

“I’m a strong believer in tradition,” he said with a laugh. “My personal celebration will have a designated driver.”

Wine is woven throughout narratives in the ancient Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. So fermented fruit of the vine has been a central part of Jewish and Christian religious rituals for thousands of years.

For many people in the pews on any given Sabbath, wine just magically appears at the altar.