| The "Day of Atonement" is the English phrase for Yom Kippur. The shoresh [root] for the word "Kippur" is kafar(כָּפַר), which probably derives from the word kofer,meaning "ransom." This word is parallel to the word "redeem" (Psalm 49:7) and means "to atone by offering a substitute." The great majority of usages in the Tanakh concern "making an atonement" by the priestly ritual of sprinkling of sacrificial blood to remove sin or defilement (i.e., tahora). The life blood of the sacrificial animal was required in exchange for the life blood of the worshipper (the symbolic expression of innocent life given for guilty life). This symbolism is further clarified by the action of the worshipper in placing his hands on the head of the sacrifice (semichah) and confessing his sins over the animal (Lev. 16:21; 1:4; 4:4, etc.) which was then killed or sent out as a scapegoat. The shoresh also appears in the term Kapporet [the so-called "Mercy Seat," but better rendered as simply the place of atonement]. The Kapporet was the golden cover of the sacred chest in the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle (or Temple) where the sacrificial blood was presented.

כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם הִוא

וַאֲנִי נְתַתִּיו לָכֶם עַל־הַמִּזְבֵּחַ

לְכַפֵּר עַל־נַפְשׁתֵיכֶם

כִּי־הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר kee ne·fesh ha·ba·sar ba·dahm hee The message of the central book of the Torah (Leviticus) is that since God is holy, we must be holy in our lives as well, and this means first of all being conscious of the distinction between the sacred and the profane, the clean and the unclean, and so on: "You are to distinguishbetween the holy (i.e., ha-kadosh: הַקּדֶשׁ) and the common (i.e., ha-chol: הַחל), and between the unclean (i.e., ha-tamei: הַטָּמֵא) and the clean (i.e., ha-tahor:הַטָּהוֹר)" (Lev. 10:10, see also Ezek. 44:23). Just as God separated the light from the darkness (Gen. 1:4), so we are called to discern between (בֵּין) the realms of the holy and the profane, the sacred and the common, and the clean and the unclean. Indeed, the Torah states "God called the light Day, and the darkness he called night," thereby associating His Name with the light but not with the darkness (Gen. 1:5).

Spiritually understood, the Mishkan (i.e., Tabernacle) physically represented the separation of these realms, as may be illustrated with the following diagram:

|

The word "sacrifice" is korban (קָרְבָּן), which comes from the root karov (קָרַב) meaning to "draw close" or "to come near." In the Tabernacle, korbanot (קָרְבָּנוֹת) were various ritual acts that were offered upon the altar to cleanse the unclean sinner so that he or she could draw near to a Holy God. Because of this, God instituted sacrificial blood as the cleansing agent that purified from the effects of defilement and sin (Lev. 17:11; Heb. 9:22). We can see the general process of purification by considering the case of the metzora (or "leper") as described in Leviticus 14 in a ritual that somewhat resembled the elaborate Yom Kippur ritual performed by the High Priest. | | | | The Torah Observance | | | | The Role of the High Priest | |

|  | | Every year on Tishri 10 the Kohen Gadol [High Priest] would perform a special ceremony to purge defilement from the Tabernacle (mishkan) or Temple (Bet Ha-Mikdash) as well as from the people of Israel (see Leviticus 16 for the details). In particular, in addition to the regular daily offerings, he would bring a bull and two goats as a special offering, and the bull would be sacrificed to purge the mishkan/temple from the defilements caused by misdeeds of the priests and their households (Leviticus 16:6). He would sprinkle the blood of the bull inside the veil of the Holy of Holies upon the kapporet (i.e., the cover of the Ark of the Covenant). Then he would draw lots and select one of the two goats to be a sin offering on behalf of the people (this goat was designated L'Adonai - "to the LORD"). He would likewise enter the Holy of Holies sprinkle the blood of the goat upon the kapporet (note that the idea that the Kohen Gadol had a rope tied around his ankle in case he died when performing these duties is likely a medieval legend). Finally, the High Priest would lay both hands upon the head of the second goat (designated "for Azazel") while confessing all of the transgressions of the people. This goat was then driven away into the wilderness, carrying on it "all their iniquities unto a land not inhabited" (Lev. 16:22). According to the Talmud, a scarlet cord was tied around the neck of the scapegoat that was reported to have turned white as the goat was led away from city. However, for the last forty years before the Temple was destroyed (in AD 70), the scarlet cord failed to change color. |

|  |  |  | | The Role of the People | | | | While the High Priest performed these functions, the people would fast in eager anticipation of the outcome of the rituals. After completing his tasks, the garments of the High Priest were covered with blood (Lev. 6:27). Only after this did the LORD accept the sacrifice (according to one midrash, as the High Priest hung out his garments, a miracle took place and his garments turned from bloodstained crimson to white; see Isaiah 1:18).

In three separate passages in the Torah, the Jewish people are told "the tenth day of the seventh month (Tishri) is the Day of Atonement. It shall be a sacred occasion for you: you shall afflict your souls" (Lev. 16:29-34, Lev. 23:26-32, Num. 29:7-11). This is the only Holiday of the year where fasting is explicitly commanded by the LORD. It also was a "Shabbat Shabbaton," or a day of complete abstention from any kind of mundane work.

It is enlightening to note the sequence of this holiday in relation to the time of preparation (Elul) and the activities surrounding Rosh Hashanah leading up to Yom Kippur. First God commands that we repent, or return to Him in earnestness of heart, and then He provides the means for reconciliation or atonement with Him. | | | Modern-day Observances of Yom Kippur | |

|  | | Though originally focused on the role of the Kohen Gadol (High Priest) and the purification of the Sanctuary, since the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD, Rabbinic tradition states that each individual Jew is supposed to focus on his personal avodah, or service to the LORD. Most Yom Kippur prayers therefore revolve around the central theme of personal repentance and return.

The Five Afflictions (ennuim)

According to halakhah (i.e., Jewish law), we must abstain from five forms of pleasures, all based on reasoning from Leviticus 23:27: - Eating and drinking

- Washing and bathing

- Applying lotions or perfume

- Wearing leather shoes

- Marital relations

By fasting and praying all day, we are said to resemble angels. By giving up the sensual pleasures of life and refraining from melakhah, we are said to live for 25 hours as if we are dead (many men wear kittels (white burial robes) and white raiment, to remind them of their fate as mortals before God).

Shabbat Shabbaton

The Torah refers to Yom Kippur as "shabbat shabbaton" (שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן), a time when all profane work (melakhah)is set aside so the soul could focus on the holiness of the LORD. The first occurrence of this phrase is found in Exodus 16:23, regarding the restriction of collecting manna in the desert during the seventh day. This restriction was later incorporated into the law code for the Sabbath day (Exod. 31:15; 35:2). The phrase also occurs regarding Rosh Hashanah (Lev. 23:24), Yom Kippur (Lev. 16:31; 23:32), two days of Sukkot (Lev. 23:39), the two days of Passover (Lev. 23:7-8), and the day of Shavuot (Num. 28:26). According to the Jewish sages, performing any form of work (other than work required to save a life) on a special Sabbath is punishable by premature death.

If you add up these days, you will find there are sevenprescribed days of "complete rest" before the LORD, and the sages identified Yom Kippur as the Sabbath of these other special Sabbath days, that is, Yom ha-kadosh (יוֹם הַקָּדוֹשׁ), "the holy day." Indeed, the Talmud notes that "seven days before Yom Kippur, we separate the High Priest," corresponding to the seven-day seclusion of Aaron and his sons before the inauguration of the Tabernacle (Lev. 8:33).

The sages say that Yom Kippur is the only day that Satan is unable to lodge accusation against Israel, since the gematria of "satan" (שָׂטָן) is 364, suggesting that the accuser denounces Israel 364 days of the year, but on the 365th day - Yom Kippur - he is rendered powerless, just as he will be in the world to come (Maharsha on Yoma 2a).

Note that those who trust in God's salvation understand that our ultimate "rest" is given to us in Yeshua, our great High Priest after the order of Malki-Tzedek, who presented his own blood to make "at-one-ment" for our souls before the Father in the Holy of Holies made without hands - at the cross.... |

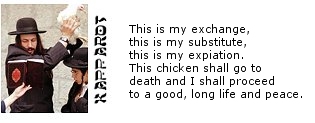

|  |  | | The Kapparot Ceremony | | | | Among Ultra-Orthodox Jews there is a minhag (custom) called kapparot(כַּפָּרוֹת) that is often performed before erev Yom Kippur. This is a sort of "scapegoat" ceremony in which a person's sins are symbolically transferred to a rooster or hen. First, various verses from the Psalms and the Book of Job are recited. Then the live chicken is swung around the head three times while the following declaration is made: "This fowl shall be in my place, it shall be my atonement, my expiation. It shall go to death, and I shall proceed to a good, long life and peace." |

| |

|  | | The chicken is then taken to a shochet (kosher butcher) to be slaughtered and given to the poor for their Erev Yom Kippur meal (seudah ha-mafseket). Those who study the Torah understand the need for blood sacrifice-- the "life-for-life" principle implied in the Torah's sacrificial system.

According to Encyclopedia Judaica, the custom was first discussed by Jewish scholars in the ninth century. They explained that since the Hebrew word gever can mean both "man" or "rooster," the punishment of the bird could be substituted for that of a person. Later, the widely influential medieval kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria (1574-1532) endorsed the ritual, and therefore many Kabbalists continue the practice to this day. |

|  |  | | Presumably, the sacrifice of the chicken is meant to take the place of the sacrifices offered at the Temple. |

|

|  | | The requirement for blood sacrifice -- the "life-for-life" principle -- is the heart of the Torah's sacrificial system. The kapparot ceremony is therefore an clear acknowledgment of the authority of Leviticus 17:11, the key verse of substitutionary atonement given in the Torah: "For the life of the flesh is in the blood (כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם), and I have given it for you on the altar to atone (לְכַפֵּר) for your souls, for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life (כִּי־הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר)." A person who studies and believes the written Torah understands the clear need for blood atonement - notwithstanding the rationalizations developed by later rabbinical Judaism.

Some people also observe Erev Yom Kippur by going to the mikveh - the ritual bath - to purify themselves before the Holy Day. Jewish tradition also states that forgiveness can be sought from God only for those sins committed against God (for example, by breaking His laws). Sins committed against others must be confessed and reconciliation sought from the offended party - and then forgiveness may be sought also from God (Matt 5:23-4). The process of making amends with others we have harmed is called mechilah (מְחִילָה). Reconciliation is often attempted during Elul and the period of Selichot. |

|  | | Erev Yom Kippur |

|  | | The Meal before Yom Kippur

The Yom Kippur fast begins an hour before sundown on Tishri 9, and lasts for 25 hours, until an hour past sundown on Tishri 10 (Lev. 23:32). Unlike other Jewish holidays that last for two days (due to the uncertainty of the calendar), the sages only required the fast to last for one full day and night. The sages state that "afflicting the soul" (i.e., fasting, etc.) is notundertaken to punish ourselves for our sins, but rather to help us focus entirely on our spiritual side. Indeed the Hebrew word for used for "afflict" (עָנָה) means to humble yourself... Note that there is no prescribed Hebrew blessing to be recited for the fast, since a blessing is not recited over not doing something.

On Erev Yom Kippur, a special meal (seudah ha-mafseket) is usually prepared - the last meal before sundown - and certain erev Yom Kippur blessings are recited. This meal includes the holiday candle lightingblessing ("Baruch Atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melekh Ha-olam, asher kidshanu b'mitzvotav vitzivanu l'hadlik ner shel Yom Ha-kippurim") and the Shehecheyanu. A memorial candle (called yahrzeit) is often lit for deceased parents or grandparents, and women often wear white, while men wear "kittels" (white robes also used for burial shrouds). After eating, it is customary to wish everyone present a Tzom Kal - an "easy fast." Another common greeting is "G'mar chatimah tovah" - "May you be sealed (in the Book of Life) for good." |

|  | | Yom Kippur Synagogue Services |

|  | | Most of Yom Kippur is spent at the synagogue praying and listening to chants. In fact, Yom Kippur is the only Jewish Holiday that requires five separate services for the observant Jew to attend! This day is, essentially, your last appeal, your last chance to change "the judgment of God" and to demonstrate your repentance and make amends.

Recall from Rosh Hashanah that one of the themes of the Days of Awe is that God has "books" that He writes our names in, noting who will live and who will die in the forthcoming year. These books are "written" on Rosh Hashanah, but our deeds during the Days of Awe can alter God's decree. The actions that change the decree are teshuvah(repentance), tefillah (prayer) and tzedakah (charity, good deeds). The books are "closed and sealed" on Yom Kippur. |

| |

|  | | As with Rosh Hashanah, a white satin parokhet (curtain which adorns the ark in the synagogue, mimicking the curtain which separated the sanctuary from the Holy of Holies in the Temple), is hung in place of the heavy velvet one used at other times.

- The Kol Nidrei (כָּל נִדְרֵי) Service

The evening service begins with the Kol Nidrei (i.e., כָּל נִדְרֵי, "all vows"], an Aramaic chant that declares null and void any promises made during the previous year (Sephardim) or for the coming year (Ashkenazim). Kol Nidrei is actually considered a "legal procedure," and therefore entails the use of various halakhic [legal] formulations such as recitation three times before a minyan, before sundown, and so on. Normally tallit [prayer shawls] are worn only in the morning service, but during Yom Kippur, they are worn during all of the services. The Aron HaKodesh (Torah cabinet) is left open while the Torah scrolls are carried around the synagogue before Kol Nidrei to indicate that the Gates of Repentance are open.

- The Ma'ariv Service

The Ma'ariv (evening) service consists of the recitation of Kaddish, the Shema, the Amidah(standing prayer), along with the confession of sins and additional prayers (selichot) that are recited only on the night of Yom Kippur. In addition, liturgical poems (piyyutim) are recited as well. Most of this service is spent reading from a machzor (High Holiday prayerbook).

The Ma'ariv service is chanted in a different style and additions to the Amidah are made, including the Vidduy (וִדּוּי), or confessional. The obligation of Vidduy derives from Scripture: "If a man or woman sins against his fellow man, thus being untrue to God..., they must confess the sin that he has committed" (Numbers 5:6-7). Note the plural personal pronoun used in the confession - implying that the sin of an individual is also borne by the community. Vidduy is said in the plural because we are all responsible for one another (Shavu'ot 39a).

Viduy prayers comprise two main sections: the Ashamnu ('We have trespassed'), a shorter, more general list of sins ("we have been treasonable, we have been aggressive, we have been slanderous" - sometimes sung) and the Al Chet, a longer, alphabetically arranged, and more particular list of sins ("for the sin that we have sinned before you forcibly or willingly, and for the sin that we have sinned before you by acting callously").

When viduy is recited, you should strike the breast lightly as if to say, "You (my heart) caused me to sin" (Mishnah Berurah 603:7). Viduy is recited ten times over the course of the five services of Yom Kippur, paralleling the Ten Commandments which have been violated.

- The Shacharit Service

The Shacharit (morning) service is not unlike other services for festivals during the Jewish year. The traditional morning prayers, the recitation of the Shema and Amidah, and the Torah reading are all part of the service. During Torah reading service there are six aliyot (separate readings by different people), one more than on other holidays (though if Yom Kippur occurs on Shabbat, there are seven aliyot).

The Torah's name for the Day of Atonement is Yom Ha-Kippurim (יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים), meaning "the day of covering, canceling, pardon, reconciling." Under the Levitical system of worship, the High Priest would sprinkle sacrificial blood upon the Kapporet (כַּפּרֶת) - the covering of the Ark of the Covenant - to effect "purification" (i.e., kapparah: כַּפָּרָה) for the previous year's sins. Notice that Yom Kippur was the only time when the High Priest could enter the Holy of Holies and invoke the sacred Name of YHVH (יהוה) to offer blood sacrifice for the sins of the Jewish people. This "life for a life" principle is the foundation of the sacrificial system and marked the great day of intercession made by the High Priest on behalf of Israel.

- The Yizkor (יִזְכּר) Service

The Yizkor portion of Yom Kippur functions as a memorial service for family members who have died. Traditionally it is recited following the Torah reading of the Shacharit service, though some communities do it in the early afternoon.

- The Musaf (מוּסָף) Service

The Musaf (additional) service immediately follows the morning service and is divided into two parts: the repetition of the Amidah (by the cantor) and the "Avodah" service, which recounts the priestly service for Yom Kippur in ancient times. In four places of the service, some people might prostrate themselves (during the re-telling of the High Priest and his confessions). After this, a portion of the service is devoted to the retelling of how some early Jewish sages were martyred during the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian. The Musaf service ends with the "Aaronic benediction" (i.e., birkat kohanim).

- Minchah Service

The Minchah (afternoon) service includes a Torah reading service (Leviticus 18), another repetition of the Amidah, and the recitation of the "Avinu Malkenu" poem. In addition, since it focuses on the importance of teshuvah (repentance) and prayer, the entire Book of Jonah is recited as the Haftarah portion of the Torah service.

- The Ne'ilah (נְעִילָה) Service

According to Jewish tradition, on Rosh Hashanah the destiny of the righteous (the tzaddikim) are written in the Book of Life, and the destiny of the wicked (the resha'im) are written in the Book of Death. However, many people (perhaps most people) will not be inscribed in either book, but have ten days -- until Yom Kippur -- to repent before sealing their fate. On Yom Kippur, then, a final appeal is made to God to be written in the Book of Life.

The word ne'ilah (נְעִילָה) comes from a word which means "closing" or "locking" [the gates of heaven (or the Temple Gates)]. The appeal to have our names "sealed" in the Book of Life" is made at this time. This closing service has a sense of urgency about it, and concludes with a responsive reading of the Shema, with the phrase "barukh shem kavod malkhuto l'olam va-ed" said aloud three times, and the phrase "the LORD He is God (i.e., Adonai hu ha-Elohim: יְהוָה הוּא הָאֱלהִים) is repeated seven times by the entire congregation (1 Kings 18:39).

(Note: During the time of the Second Temple, the High Priest would say aloud the sacred Name "YHVH" three times during the Yom Kippur avodah. During each confession, when the priest would say the Name, all the people would prostrate themselves and say aloud, Baruch shem K'vod malchuto l'olam va'ed- "Blessed be the Name of the radiance of the Kingship, forever and ever.")

This declaration is followed by a long, final blast of the shofar (i.e., tekiah gedolah), the "great shofar," to remind us how the shofar was sounded to proclaim the Year of Jubilee Year (יוֹבֵל) of freedom throughout the land (Lev. 25:9-10).

|

|  | | Worshippers then exclaim, "L'shanah haba'ah b'Yerushalayim!" After the service ends, some synagogues perform also a Havdalah ceremony.

At this point, people are generally quite relieved that they have "made it" through the Days of Awe, and a celebratory mood sets in (traditionally a time of courtship and love follow this holiday). Since Sukkotis only five days away, it is common to begin planning to set up your sukkah for the upcoming holiday.

|

|  | | Yom Kippur Torah Readings |

|  | | Yom Kippur and the New Covenant |

|  |  | | One of the roles of our beloved Mashiach Yeshua (Jesus Christ) is that of Kohen HaGadol (High Priest) who offered true kapparah [atonement] for our sins by offering His own blood in the Holy of Holies made without hands. |

|

|  | | As it is written in the letter of Hebrews: |

|  | | Therefore, holy brothers, you who share in a heavenly calling, consider Jesus, the apostle and high priest of our confession, who was faithful to him who appointed him, just as Moses also was faithful in all God's house. (Hebrews 3:1-2) |

|  | | The Importance of a Blood Sacrifice |

|  | | The importance of blood sacrifice (i.e., substitutionary atonement) cannot be overstated in the Scriptures since it constitutes the fundamental means of atonement that is given through the sacrificial system. Indeed this principle is enshrined in the central text of sacrifice itself, Leviticus 17:11:

כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם הִוא

וַאֲנִי נְתַתִּיו לָכֶם עַל־הַמִּזְבֵּחַ

לְכַפֵּר עַל־נַפְשׁתֵיכֶם

כִּי־הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר kee ne·fesh ha·ba·sar ba·dahm hee

va·a·nee ne·ta·teev la·khem al ha·meez·bei·ach

le·kha·peir al naf·sho·tei·khem

kee ha·dahm hoo ba·ne·fesh ye·kha·peir

"For the life of the flesh is in the blood,

and I have given it for you on the altar to atone for your souls,

for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life."

Hebrew Study Card

A blood sacrifice is required by the LORD for the issue of sin. Leviticus 17:11 agrees with the teaching in the New Testament in Hebrews 9:22: "Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins" (χωρὶς αἱματεκχυσίας οὐ γίνεται ἄφεσις). In the Talmud (Yoma 5a) it is likewise written, "There is no atonement without blood." The substitutionary shedding of blood, the "life-for-life" principle, is essential to true "at-one-ment" with the LORD God.

Yeshua offered His own body up to be the perfect Sacrifice for sins. By His shed blood we are given complete atonement before the LORD. "For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God" (2 Cor. 5:21). The Levitical system of animal sacrifices, including the elaborate Yom Kippur ritual, was meant to foreshadowthe true and abiding Sacrifice of Yeshua as the means of our reconciliation with God. The B'rit Yeshanah (Old Covenant) provides a shadow of the substance revealed in the B'rit Chadashah (New Covenant). If the old covenant had been sufficient to provide a permanent solution to the problem of our sin, there never would have been need for a new covenant to supercede it (Hebrews 8:7).

Under the old covenant, sacrifices merely "covered" sins, but under the new covenant, these sins are taken entirely away (Hebrews 7:27, 9:12, 9:25-28). There is no more need for continual sacrifices, since Yeshua provided the once-and-for-all sacrifice for all of our sins (Hebrews 9:11-14; 9:24-28; 10:11-20).

Indeed, Yeshua ha-Mashiach is the "propitiation" or "expiation" for our sins. The Greek word used in Romans 3:25, 1 John 2:2, and 1 John 4:10 ("hilasterion") is the same word used in the LXX for the kapporet [cover of the ark of the covenant] in the Holy of Holies which was sprinkled with the blood of the sacrifice on Yom Kippur. For Messiah has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf. Nor was it to offer himself repeatedly, as the high priest enters the holy places every year with blood not his own, for then he would have had to suffer repeatedly since the foundation of the world. But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself... So Messiah, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him (Heb. 9:24-ff).

For by one offering he hath perfected for ever them that are sanctified (Heb. 10:14).

|

|  | | What do Messianic Jews do regarding Yom Kippur? Do we fast, afflict ourselves, and confess our sins, or do we rejoice in the knowledge that we are forgiven of all our sins because of Yeshua's perfect avodah as our Kohen Gadol of the New Covenant? In other words, should we be sad and afflicted or should we be happy and comforted?

In post-Temple Judaism (i.e., rabbinical Judaism) it is customary for Jews to wish one another g'mar chatimah tovah (גְּמַר חַתִימָה טוֹבָה), "a good final sealing" during the Ten Days of Awe (i.e., the ten days running from Rosh Hashanah until Yom Kippur). The reason for this is that according to Jewish tradition the "writing of God's verdict" (for your life) occurs on Rosh Hashanah, but the "sealing of the verdict" occurs on Yom Kippur. In other words, God in His Mercy gives us another ten days to do "teshuvah" before sealing our fate.... But it's up to us -- and our teshuvah -- to "save ourselves" from God's decree of death. Our merits (mitzvot) are the key: וּתְשׁוּבָה וּתְפִלָּה וּצְדָקָה מַעֲבִירִין אֶת רעַ הַגְּזֵרָה / "Teshuvah, prayer, and charity deliver us from the evil decree."

Of course as Messianic Jews (and Christians) we have a permanent "sealing" for good by the grace and love of God given to us in Yeshua our Messiah (Eph. 1:13, 4:30; 2 Cor. 1:21-22). The Torah's statement that sacrificial blood was offered upon the altar to make atonement (כַּפָּרָה) for our souls (Lev. 17:11) finds its final application in the "blood work" of Yeshua upon the cross at Moriah (Rom. 5:11). The substitutionary shedding of blood, the "life-for-life" principle, is essential to the true "at-one-ment" with God. The ordinances of the Levitical priesthood were just "types and shadows" of the coming Substance that would give us everlasting atonement with God (Heb. 8-10). Because of Yeshua, we have a Kohen Gadol (High Priest) of the better Covenant, based on better promises (Heb. 8:6). For this reason it is entirely appropriate to celebrate Yom Kippur and give thanks to the LORD for the permanent "chatimah tovah" given to us through the salvation of His Son.

It must always be remembered that Torah (תּוֹרָה) is a "function word" that expresses our responsibility in light of the covenantal acts of God. As the author of the Book of Hebrews makes clear: "When there is a change in the priesthood (הַכְּהוּנָּה), there is necessarily (ἀνάγκη) a change in the Torah as well" (Heb. 7:12). The Levitical priesthood expresses the Torah of the Covenant of Sinai (בְּרִית יְשָׁנָה), just as the greater priesthood of Yeshua expresses the Torah of the New Covenant (בְּרִית חֲדָשָׁה).

Still, for the Messianic Jewish believer there is a bit of ambivalence about this holiday, perhaps more than any other of the Jewish year. Part of this ambivalence comes from the "already-not-yet" aspect of the New Covenant itself. Already Yeshua has come and offered Himself up as kapparah (atonement/propitiation) for our sins; already He has sent the Ruach Hakodesh (Holy Spirit) to write truth upon our hearts; already He is our God and we are His people. However, the New Covenant is not yetultimately fulfilled since we await the return of Yeshua to restore Israel and establish His kingdom upon the earth... Since prophetically speaking Yom Kippur signifies ethnic Israel's atonement secured through Yeshua's sacrificial avodah as Israel's true High Priest and King, there is still a sense of longing and affliction connected to this holiday that will not be removed until finally "all Israel is saved." So, on the one hand we celebrate Yom Kippur because it acknowledges Yeshua as our High Priest of the New Covenant, but on the other hand, we "have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in our hearts" for the redemption of the Jewish people and the atonement of their sins (Rom. 9:1-5; 10:1-4; 11:1-2, 11-15, 25-27). In the meantime, we are in a period of "mysterious grace" (yemot ha-mashiach) wherein we have opportunity to offer the terms of the New Covenant to people of every nation, tribe and tongue. After the "fullness of the Gentiles" is come in, however, God will turn His full attention to fulfilling His promises given to ethnic Israel. That great Day of the LORD is coming soon, chaverim...

The Book of Life

Some Messianic Jews observe Yom Kippur (i.e., keep the 25 hour fast, confess sins, etc.) in order to better identify with the Jewish people, while others might observe it as a special time of personal confession and teshuvah. We are careful, however, to keep in mind that such observance does not grant us a "favorable judgment" before the LORD or determine whether our names will be written in Sefer ha-chayim (the Book of Life), since Yeshua's sacrifice and intercession is all we need for at-one-ment with the Father. Those who belong to Yeshua are indeed written in the "Lamb's book of life" (Phil. 4:3; Rev. 3:5; 13:8; 17:8; 20:12, 15; 21:27; 22:19).

What is Sefer ha-chayim? This is the allegorical book in which God records the names and lives of the righteous (tzaddikim). According to the Talmud it is open on Rosh Hashanah (the Book of the Dead, sefer hametim, is open on this date as well) and God then examines each soul to see if teshuvah is sh'leimah (complete). If a person turns to God and makes amends to those whom he has harmed, he will be given another year to live in the following (Jewish) year. On the other hand, if he does not repent, then the decree may be given that he will die during the coming year...

In Jewish tradition, Yom Kippur is essentially your last appeal, your last chance to change "the judgment of God" and to demonstrate your repentance and make amends. The books are "written" on Rosh Hashanah, but our deeds during the Ten Days of Awe can alter God's decree. The actions that change the decree are teshuvah(repentance), tefilah (prayer) and tzedakah (good deeds). The books are then "sealed" on Yom Kippur.

Again, it is important to keep in heart that those who are trusting in Yeshua as their Atonement before the Father are thereby declared tzaddikim and their names are written (and sealed) in the Book of Life. The Day of Judgment for our sinful lives has come in the Person of Yeshua the Mashiach, blessed be He. All those who truly belong to Yeshua are written in the "Lamb's book of life " (Phil. 4:3; Rev. 3:5; 13:8; 17:8; 20:12, 15; 21:27; 22:19). Yom Kippur is therefore a time of joy for us, since we have g'mar chatimah tovah (גְּמַר חַתִימָה טוֹבָה), "a good and final sealing," in the Lamb's Book of Life because of Messiah Yeshua, our Great High Priest after the order of Malki-Tzedek!

The traditional viduy (a confessional prayer consisting of two parts, ashamnu and al chet) is written using the first person plural: "We have sinned..." since kol Yisrael arevim zeh bazeh - "All Israel is responsible for one another." Traditionally al chet is recited ten times during the course of the five Yom Kippur services (once for each of the 10 commandments that we have broken). Here's how it starts:

Al Chet...

For the sin which we have committed before You under duress or willingly.

And for the sin which we have committed before You by hard-heartedness.

For the sin which we have committed before You inadvertently.

And for the sin which we have committed before You with an utterance of the lips.

For the sin which we have committed before You with immorality....

For all of these, God of pardon, pardon us, forgive us...

(continues...) (continues...)

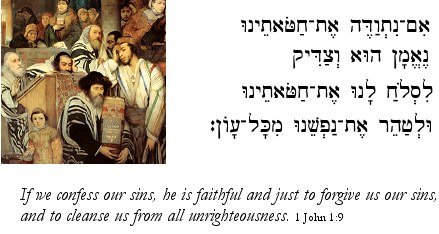

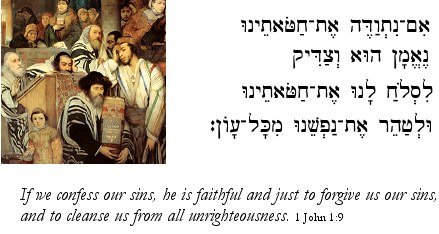

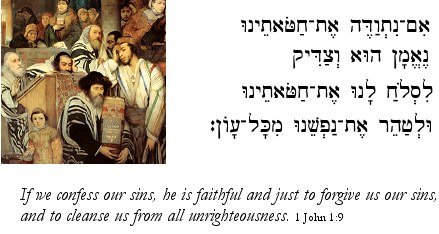

Confession is vitally important for Messianic Jews and Christians, since it both reminds us of our great need for God's intervention in our lives, and also helps us walk in the truth. "If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just, to forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness" (1 John 1:9). "Confess your faults one to another, and pray one for another, that ye (plural) may be healed" (James 5:16).

Eschatologically, Yom Kippur represents the national restoration of Israel at the end of the Great Tribulation period, but it also is a reminder of the terrible cost of sin in our lives. Sin is so offensive and the debt is so great that it took nothing less than the sacrifice of Yeshua Himself in order to secure our reconciliation with God. We therefore should tremble with fear before God in reverent gratitude of His mercy toward us.

Yom Ha-Din - Judgment Day

As Messianic believers, we maintain that Judgment Day has come and justice was served through the sacrificial offering of Yeshua for our sins (2 Cor. 5:21). He is the perfect fulfillment of the Akedah of Isaac. Our names are written in the Lamb's Book of Life, or Sefer HaChayim (Rev. 13:8). We do not believe that we are made acceptable in God's sight by means of our own works of righteousness (Titus 3:5-6), though that does not excuse us from being without such works (as fruit of the Holy Spirit in our lives). The Scriptures clearly warn that on the Day of Judgment to come, anyone's name not found written in the Book of Life will be thrown into the lake of fire (Rev. 20:15). Moreover, all Christians will stand before the Throne of Judgment to give account for their lives (2 Cor. 5:10). "Every man's work shall be made manifest: for the day shall declare it, because it shall be revealed by fire; and the fire shall try every man's work of what sort it is" (1 Cor. 3:13). Life is an examination, a test, and every moment is irrepeatable. Every "careless" word we utter will be echoed on the Day of Judgment (Matt. 12:36-37). Our future day of judgment is being decided today....

The spring festivals (Passover, Firstfruits, and Shavuot) have been perfectly fulfilled in the first coming of Yeshua as Mashiach ben Yosef, and the fall festivals (Yom Teruah, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot) will be fulfilled in His second coming as Mashiach ben David. Since the first advent fulfilled all of the spring mo'edim to the smallest of details, we believe that His second advent portends similar fulfillment as revealed in the fall mo'edim.

After the summer of harvest (John 4:35), the very first fall festival on the Jewish calendar is Yom Teruah (Rosh Hashanah), which is a picture of the "catching away" of kallat Mashiach (the Bride of Christ) for the time of Sheva Berachot (seven "days" of blessing that follows the marriage ceremony). Then will come the Great Tribulation and the "great Day of the LORD" (יוֹם־יְהוָה הַגָּדוֹל). During this time, ethnic Israel will be fully restored to the LORD and their sins will be purged (see Matthew 24). Yeshua will then physically return to Israel to establish His glorious millennial kingdom in Zion. Finally "all Israel will be saved" (Rom. 11:26) and Yeshua will be coronated as the King of King of Kings - Melech Malchei Ha-Melachim (מֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְּלָכִים).

May His Kingdom come speedily, and in our day. Amen. |

Worshippers then exclaim, "L'shanah haba'ah b'Yerushalayim!" After the service ends, some synagogues perform also a Havdalah ceremony.

At this point, people are generally quite relieved that they have "made it" through the Days of Awe, and a celebratory mood sets in (traditionally a time of courtship and love follow this holiday). Since Sukkotis only five days away, it is common to begin planning to set up your sukkah for the upcoming holiday.

|

|  | | Yom Kippur Torah Readings |

|  | | Yom Kippur and the New Covenant |

|  |  | | One of the roles of our beloved Mashiach Yeshua (Jesus Christ) is that of Kohen HaGadol (High Priest) who offered true kapparah [atonement] for our sins by offering His own blood in the Holy of Holies made without hands. |

|

|  | | As it is written in the letter of Hebrews: |

|  | | Therefore, holy brothers, you who share in a heavenly calling, consider Jesus, the apostle and high priest of our confession, who was faithful to him who appointed him, just as Moses also was faithful in all God's house. (Hebrews 3:1-2) |

|  | | The Importance of a Blood Sacrifice |

|

The importance of blood sacrifice (i.e., substitutionary atonement) cannot be overstated in the Scriptures since it constitutes the fundamental means of atonement that is given through the sacrificial system. Indeed this principle is enshrined in the central text of sacrifice itself, Leviticus 17:11:

כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם הִוא

וַאֲנִי נְתַתִּיו לָכֶם עַל־הַמִּזְבֵּחַ

לְכַפֵּר עַל־נַפְשׁתֵיכֶם

כִּי־הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר kee ne·fesh ha·ba·sar ba·dahm hee

va·a·nee ne·ta·teev la·khem al ha·meez·bei·ach

le·kha·peir al naf·sho·tei·khem

kee ha·dahm hoo ba·ne·fesh ye·kha·peir

"For the life of the flesh is in the blood,

and I have given it for you on the altar to atone for your souls,

for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life."

Hebrew Study Card

A blood sacrifice is required by the LORD for the issue of sin. Leviticus 17:11 agrees with the teaching in the New Testament in Hebrews 9:22: "Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins" (χωρὶς αἱματεκχυσίας οὐ γίνεται ἄφεσις). In the Talmud (Yoma 5a) it is likewise written, "There is no atonement without blood." The substitutionary shedding of blood, the "life-for-life" principle, is essential to true "at-one-ment" with the LORD God.

Yeshua offered His own body up to be the perfect Sacrifice for sins. By His shed blood we are given complete atonement before the LORD. "For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God" (2 Cor. 5:21). The Levitical system of animal sacrifices, including the elaborate Yom Kippur ritual, was meant to foreshadowthe true and abiding Sacrifice of Yeshua as the means of our reconciliation with God. The B'rit Yeshanah (Old Covenant) provides a shadow of the substance revealed in the B'rit Chadashah (New Covenant). If the old covenant had been sufficient to provide a permanent solution to the problem of our sin, there never would have been need for a new covenant to supercede it (Hebrews 8:7).

Kippur fast begins an hour before sundown on Tishri 9, and lasts for 25 hours, until an hour past sundown on Tishri 10 (Lev. 23:32). Unlike other Jewish holidays that last for two days (due to the uncertainty of the calendar), the sages only required the fast to last for one full day and night. The sages state that "afflicting the soul" (i.e., fasting, etc.) is notundertaken to punish ourselves for our sins, but rather to help us focus entirely on our spiritual side. Indeed the Hebrew word for used for "afflict" (עָנָה) means to humble yourself... Note that there is no prescribed Hebrew blessing to be recited for the fast, since a blessing is not recited over not doing something.

On Erev Yom Kippur, a special meal (seudah ha-mafseket) is usually prepared - the last meal before sundown - and certain erev Yom Kippur blessings are recited. This meal includes the holiday candle lightingblessing ("Baruch Atah, Adonai Eloheinu, Melekh Ha-olam, asher kidshanu b'mitzvotav vitzivanu l'hadlik ner shel Yom Ha-kippurim") and the Shehecheyanu. A memorial candle (called yahrzeit) is often lit for deceased parents or grandparents, and women often wear white, while men wear "kittels" (white robes also used for burial shrouds). After eating, it is customary to wish everyone present a Tzom Kal - an "easy fast." Another common greeting is "G'mar chatimah tovah" - "May you be sealed (in the Book of Life) for good." |

|  | | Yom Kippur Synagogue Services |

|  | | Most of Yom Kippur is spent at the synagogue praying and listening to chants. In fact, Yom Kippur is the only Jewish Holiday that requires five separate services for the observant Jew to attend! This day is, essentially, your last appeal, your last chance to change "the judgment of God" and to demonstrate your repentance and make amends.

Recall from Rosh Hashanah that one of the themes of the Days of Awe is that God has "books" that He writes our names in, noting who will live and who will die in the forthcoming year. These books are "written" on Rosh Hashanah, but our deeds during the Days of Awe can alter God's decree. The actions that change the decree are teshuvah(repentance), tefillah (prayer) and tzedakah (charity, good deeds). The books are "closed and sealed" on Yom Kippur. |

| |

|  | | As with Rosh Hashanah, a white satin parokhet (curtain which adorns the ark in the synagogue, mimicking the curtain which separated the sanctuary from the Holy of Holies in the Temple), is hung in place of the heavy velvet one used at other times.

- The Kol Nidrei (כָּל נִדְרֵי) Service

The evening service begins with the Kol Nidrei (i.e., כָּל נִדְרֵי, "all vows"], an Aramaic chant that declares null and void any promises made during the previous year (Sephardim) or for the coming year (Ashkenazim). Kol Nidrei is actually considered a "legal procedure," and therefore entails the use of various halakhic [legal] formulations such as recitation three times before a minyan, before sundown, and so on. Normally tallit [prayer shawls] are worn only in the morning service, but during Yom Kippur, they are worn during all of the services. The Aron HaKodesh (Torah cabinet) is left open while the Torah scrolls are carried around the synagogue before Kol Nidrei to indicate that the Gates of Repentance are open.

- The Ma'ariv Service

The Ma'ariv (evening) service consists of the recitation of Kaddish, the Shema, the Amidah(standing prayer), along with the confession of sins and additional prayers (selichot) that are recited only on the night of Yom Kippur. In addition, liturgical poems (piyyutim) are recited as well. Most of this service is spent reading from a machzor (High Holiday prayerbook).

The Ma'ariv service is chanted in a different style and additions to the Amidah are made, including the Vidduy (וִדּוּי), or confessional. The obligation of Vidduy derives from Scripture: "If a man or woman sins against his fellow man, thus being untrue to God..., they must confess the sin that he has committed" (Numbers 5:6-7). Note the plural personal pronoun used in the confession - implying that the sin of an individual is also borne by the community. Vidduy is said in the plural because we are all responsible for one another (Shavu'ot 39a).

Viduy prayers comprise two main sections: the Ashamnu ('We have trespassed'), a shorter, more general list of sins ("we have been treasonable, we have been aggressive, we have been slanderous" - sometimes sung) and the Al Chet, a longer, alphabetically arranged, and more particular list of sins ("for the sin that we have sinned before you forcibly or willingly, and for the sin that we have sinned before you by acting callously").

When viduy is recited, you should strike the breast lightly as if to say, "You (my heart) caused me to sin" (Mishnah Berurah 603:7). Viduy is recited ten times over the course of the five services of Yom Kippur, paralleling the Ten Commandments which have been violated.

- The Shacharit Service

The Shacharit (morning) service is not unlike other services for festivals during the Jewish year. The traditional morning prayers, the recitation of the Shema and Amidah, and the Torah reading are all part of the service. During Torah reading service there are six aliyot (separate readings by different people), one more than on other holidays (though if Yom Kippur occurs on Shabbat, there are seven aliyot).

The Torah's name for the Day of Atonement is Yom Ha-Kippurim (יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים), meaning "the day of covering, canceling, pardon, reconciling." Under the Levitical system of worship, the High Priest would sprinkle sacrificial blood upon the Kapporet (כַּפּרֶת) - the covering of the Ark of the Covenant - to effect "purification" (i.e., kapparah: כַּפָּרָה) for the previous year's sins. Notice that Yom Kippur was the only time when the High Priest could enter the Holy of Holies and invoke the sacred Name of YHVH (יהוה) to offer blood sacrifice for the sins of the Jewish people. This "life for a life" principle is the foundation of the sacrificial system and marked the great day of intercession made by the High Priest on behalf of Israel.

- The Yizkor (יִזְכּר) Service

The Yizkor portion of Yom Kippur functions as a memorial service for family members who have died. Traditionally it is recited following the Torah reading of the Shacharit service, though some communities do it in the early afternoon.

- The Musaf (מוּסָף) Service

The Musaf (additional) service immediately follows the morning service and is divided into two parts: the repetition of the Amidah (by the cantor) and the "Avodah" service, which recounts the priestly service for Yom Kippur in ancient times. In four places of the service, some people might prostrate themselves (during the re-telling of the High Priest and his confessions). After this, a portion of the service is devoted to the retelling of how some early Jewish sages were martyred during the reign of the Roman emperor Hadrian. The Musaf service ends with the "Aaronic benediction" (i.e., birkat kohanim).

- Minchah Service

The Minchah (afternoon) service includes a Torah reading service (Leviticus 18), another repetition of the Amidah, and the recitation of the "Avinu Malkenu" poem. In addition, since it focuses on the importance of teshuvah (repentance) and prayer, the entire Book of Jonah is recited as the Haftarah portion of the Torah service.

- The Ne'ilah (נְעִילָה) Service

According to Jewish tradition, on Rosh Hashanah the destiny of the righteous (the tzaddikim) are written in the Book of Life, and the destiny of the wicked (the resha'im) are written in the Book of Death. However, many people (perhaps most people) will not be inscribed in either book, but have ten days -- until Yom Kippur -- to repent before sealing their fate. On Yom Kippur, then, a final appeal is made to God to be written in the Book of Life.

The word ne'ilah (נְעִילָה) comes from a word which means "closing" or "locking" [the gates of heaven (or the Temple Gates)]. The appeal to have our names "sealed" in the Book of Life" is made at this time. This closing service has a sense of urgency about it, and concludes with a responsive reading of the Shema, with the phrase "barukh shem kavod malkhuto l'olam va-ed" said aloud three times, and the phrase "the LORD He is God (i.e., Adonai hu ha-Elohim: יְהוָה הוּא הָאֱלהִים) is repeated seven times by the entire congregation (1 Kings 18:39).

(Note: During the time of the Second Temple, the High Priest would say aloud the sacred Name "YHVH" three times during the Yom Kippur avodah. During each confession, when the priest would say the Name, all the people would prostrate themselves and say aloud, Baruch shem K'vod malchuto l'olam va'ed- "Blessed be the Name of the radiance of the Kingship, forever and ever.")

This declaration is followed by a long, final blast of the shofar (i.e., tekiah gedolah), the "great shofar," to remind us how the shofar was sounded to proclaim the Year of Jubilee Year (יוֹבֵל) of freedom throughout the land (Lev. 25:9-10).

|

|  | | Worshippers then exclaim, "L'shanah haba'ah b'Yerushalayim!" After the service ends, some synagogues perform also a Havdalah ceremony.

At this point, people are generally quite relieved that they have "made it" through the Days of Awe, and a celebratory mood sets in (traditionally a time of courtship and love follow this holiday). Since Sukkotis only five days away, it is common to begin planning to set up your sukkah for the upcoming holiday.

|

|  | | Yom Kippur Torah Readings |

|  | | Yom Kippur and the New Covenant |

|  |  | | One of the roles of our beloved Mashiach Yeshua (Jesus Christ) is that of Kohen HaGadol (High Priest) who offered true kapparah [atonement] for our sins by offering His own blood in the Holy of Holies made without hands. |

|

|  | | As it is written in the letter of Hebrews: |

|  | | Therefore, holy brothers, you who share in a heavenly calling, consider Jesus, the apostle and high priest of our confession, who was faithful to him who appointed him, just as Moses also was faithful in all God's house. (Hebrews 3:1-2) |

|  | | The Importance of a Blood Sacrifice |

|  | | The importance of blood sacrifice (i.e., substitutionary atonement) cannot be overstated in the Scriptures since it constitutes the fundamental means of atonement that is given through the sacrificial system. Indeed this principle is enshrined in the central text of sacrifice itself, Leviticus 17:11:

כִּי נֶפֶשׁ הַבָּשָׂר בַּדָּם הִוא

וַאֲנִי נְתַתִּיו לָכֶם עַל־הַמִּזְבֵּחַ

לְכַפֵּר עַל־נַפְשׁתֵיכֶם

כִּי־הַדָּם הוּא בַּנֶּפֶשׁ יְכַפֵּר kee ne·fesh ha·ba·sar ba·dahm hee

va·a·nee ne·ta·teev la·khem al ha·meez·bei·ach

le·kha·peir al naf·sho·tei·khem

kee ha·dahm hoo ba·ne·fesh ye·kha·peir

"For the life of the flesh is in the blood,

and I have given it for you on the altar to atone for your souls,

for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life."

Hebrew Study Card

A blood sacrifice is required by the LORD for the issue of sin. Leviticus 17:11 agrees with the teaching in the New Testament in Hebrews 9:22: "Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins" (χωρὶς αἱματεκχυσίας οὐ γίνεται ἄφεσις). In the Talmud (Yoma 5a) it is likewise written, "There is no atonement without blood." The substitutionary shedding of blood, the "life-for-life" principle, is essential to true "at-one-ment" with the LORD God.

Yeshua offered His own body up to be the perfect Sacrifice for sins. By His shed blood we are given complete atonement before the LORD. "For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God" (2 Cor. 5:21). The Levitical system of animal sacrifices, including the elaborate Yom Kippur ritual, was meant to foreshadowthe true and abiding Sacrifice of Yeshua as the means of our reconciliation with God. The B'rit Yeshanah (Old Covenant) provides a shadow of the substance revealed in the B'rit Chadashah (New Covenant). If the old covenant had been sufficient to provide a permanent solution to the problem of our sin, there never would have been need for a new covenant to supercede it (Hebrews 8:7).

Under the old covenant, sacrifices merely "covered" sins, but under the new covenant, these sins are taken entirely away (Hebrews 7:27, 9:12, 9:25-28). There is no more need for continual sacrifices, since Yeshua provided the once-and-for-all sacrifice for all of our sins (Hebrews 9:11-14; 9:24-28; 10:11-20).

Indeed, Yeshua ha-Mashiach is the "propitiation" or "expiation" for our sins. The Greek word used in Romans 3:25, 1 John 2:2, and 1 John 4:10 ("hilasterion") is the same word used in the LXX for the kapporet [cover of the ark of the covenant] in the Holy of Holies which was sprinkled with the blood of the sacrifice on Yom Kippur. For Messiah has entered, not into holy places made with hands, which are copies of the true things, but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf. Nor was it to offer himself repeatedly, as the high priest enters the holy places every year with blood not his own, for then he would have had to suffer repeatedly since the foundation of the world. But as it is, he has appeared once for all at the end of the ages to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself... So Messiah, having been offered once to bear the sins of many, will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him (Heb. 9:24-ff).

For by one offering he hath perfected for ever them that are sanctified (Heb. 10:14).

|

|  | | What do Messianic Jews do regarding Yom Kippur? Do we fast, afflict ourselves, and confess our sins, or do we rejoice in the knowledge that we are forgiven of all our sins because of Yeshua's perfect avodah as our Kohen Gadol of the New Covenant? In other words, should we be sad and afflicted or should we be happy and comforted?

In post-Temple Judaism (i.e., rabbinical Judaism) it is customary for Jews to wish one another g'mar chatimah tovah (גְּמַר חַתִימָה טוֹבָה), "a good final sealing" during the Ten Days of Awe (i.e., the ten days running from Rosh Hashanah until Yom Kippur). The reason for this is that acc

Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest and most somber day of the Jewish year. Yom Kippur concludes the Ten Days of Awe that begin with Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year). Like Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur is a prospective holiday, when we prepare for the year ahead through fasting, penitence and confession. Origin of Yom KippurGod established a Day of Atonement in Leviticus, setting down rules for it in two instances actually (Leviticus 16:29 ff. and 23:27 ff.)—an indication of the holiday’s profound importance. God tells Moses in the first of these passages: And it shall be a statute to you forever that in the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month, you shall afflict yourselves and shall do no work, either the native or the stranger who sojourns among you. For on this day shall atonement be made for you to cleanse you. You shall be clean before the LORD from all your sins. It is a Sabbath of solemn rest to you, and you shall afflict yourselves; it is a statute forever. And the priest who is anointed and consecrated as priest in his father’s place shall make atonement, wearing the holy linen garments. Leviticus 16:29-32

Yom Kippur required action from both the high priest and the people—the high priest was to make atonement through sacrifice, and the people for their part were to practice self-denial and refrain from work. Thus, all Israelites had to do their part during this collective Day of Atonement. By God’s commandment, the high priest followed a specific protocol on Yom Kippur. He bathed and dressed in white linen raiments, an act of purification, before entering the Holy of Holies. There the high priest made two sin offerings: a bull for his house and a goat for the people. The priest would lay the sins of the people on the head of a second goat, which had been chosen by lot as the “scapegoat”. After the high priest spoke the sins and iniquities of the people and put them on its head, the scapegoat would be removed into the wilderness. How Yom Kippur Is ObservedObservant Jews spend the Days of Awe that fall between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur making amends with their fellow man, so that they enter Yom Kippur in a spirit of reconciliation and atonement for past wrongs. We learn in the Scriptures that we must be in right relation with our neighbors if we are to love the Lord our God—the two go hand in hand. The V’ahavta sums up our obligations to God: “You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (Deuteronomy 6:5). A second law sums up our obligations to one another: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; see Mark 12:30). In addition to making amends, it is common to feast the day before Yom Kippur in preparation for the fast, from which children and the sick are exempt. Many observant Jews light a candle for their deceased parents on Yom Kippur, a practice also carried out on the anniversary (yahrzeit) of parents’ deaths. The day of Yom Kippur itself is observed by abstaining from work and practicing self-denial, as mandated in Leviticus. In the Talmud, “self-denial” is interpreted to mean: “it is forbidden to eat or drink, or bathe or anoint oneself or wear sandals, or to indulge in conjugal intercourse” (Yoma 8.1). By abstaining from work and indulgence, we are meant to enter a state of introspection and repentance, attending to the sins and misdeeds we have committed and acknowledging our dependence on God for redemption. Special Synagogue Readings for Yom KippurThe celebration of Yom Kippur involves a somber liturgy, which includes the absolution of congregants from ill-advised future promises (Kol Nidre), communal confession of sins (Vidui), the mourning of departed parents (Yizkor) and the blowing of the shofar. After the blowing of the shofar, Jews may break the Yom Kippur fast. The following is a non-exhaustive list of important Yom Kippur readings and liturgy: Evening service:Recitation of the Kol Nidre and the Vidui, a lengthy confession of sins

Morning Service:Torah portion: Leviticus 16:1-34, Numbers 29:7-11 Haftarah portion: Isaiah 57:14-58:14Recitation of the Yizkor, recitation of the martyrology

Afternoon Service:Torah portion: Leviticus 18:1-30 Haftarah: The Book of Jonah in its entirety, Micah 7:18-20 Recitation of the Ne’ilah prayer, the Sh’ma, the Baruch Shem; collective proclamation L’Shana Haba’ah b’Yerushalayim! (Next Year in Jerusalem!) Concludes with the blowing of the shofar

Traditional Customs and Folklore of Yom KippurAccording to tradition, Yom Kippur falls on the day Moses brought down the second set of Sacred Tablets of the Ten Commandments, the first set of which he had destroyed, and the repentant Israelites were absolved of their great sin: worshipping the Golden Calf. Maimonides writes: “It is the day on which the Master of the prophets descended with the second Tables [of the Law] and brought them the good news that their great sin was forgiven.” For this reason, Yom Kippur took on at once an air of gravity and of joy—contrition sweetened by the taste of forgiveness. It even became a time for matchmaking in ancient Israel. Tradition tells us that, on Yom Kippur, all of the girls would wear white—those who did not own white clothing were lent white raiment for this special occasion. They would go out dancing in the vineyards and the young men were permitted to see them dance. The Talmud explains: “And what did they say? ‘Young man, lift up thine eyes and see what thou wouldst choose for thyself: set not thine eyes on beauty, but set thine eyes on family; for Favor is deceitful and beauty is vain, but a woman that feareth the Lord shall be praised [Proverbs 31:30]’” (Yoma 6.1). No longer do the women go out dancing on Yom Kippur, but the tradition of wearing white on Yom Kippur lasts into our own time. Ashkenazi Jewish men imitate the high priest’s manner of dress when attending Yom Kippur service today by wearing a white kittel (a funerary shroud, reminding us of our mortality). White symbolizes purity in Jewish tradition—wedding garments, for instance, are also traditionally white. The book of Isaiah bears out this symbolic significance—God says to His people in Isaiah 1:18: “though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.” Yom Kippur in the New TestamentFor believers in Yeshua, the scapegoat is a picture of the Messiah, who was sent “as an atoning sacrifice for our sins” (1 John 4:10). Like the scapegoat, Yeshua receives our iniquities and transgressions and takes them from us; unlike the scapegoat, his sacrifice is good for all time, rather than needing to be repeated from year to year. Yom Kippur can be a conundrum to Jewish believers in Yeshua. Do we fast and confess our sins like the rest of the Jewish community, or do we rejoice in the knowledge that we have been granted lasting forgiveness in Messiah? Many Jewish believers view Yom Kippur as a time for identification with our Jewish people, introspection for ourselves and intercession for loved ones, knowing all the while that Jesus is the One that makes us at one with God. Believers in Yeshua who observe Yom Kippur recognize that, although we particularly focus on our need for repentance and forgiveness on this day, we have received ultimate, lasting atonement through Yeshua the Messiah, the Son of God. Glossary of Yom Kippur TermsAzazel– removal (associated with the scapegoat that was sent into the wilderness) High Holy Days– Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur Kol Nidre– Jewish liturgy, well-loved for its melody; the words of Kol Nidre, which is sung at the beginning of Yom Kippur, absolve Jews of any promises that may be broken in the coming year; rabbinical, not a biblical, tradition Machzor– prayer book used for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur Shabbat Shabbaton– alternative name for Yom Kippur meaning “Sabbath of Sabbaths” Shofar– ram’s horn, traditionally blown during Rosh Hashanah and at the end of Yom Kippur; used to be blown to mark the start of Jubilee, when all people in Israel were released from bondage The Ten Days of Awe– start with Rosh Hashanah and conclude with Yom Kippur; together Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are referred to as the High Holidays Teshuvah– Hebrew term for returning to the right path or penitence; the practice of atoning for one’s sins Viddui– prayer wherein we repent of having committed a long litany of sins (similar in nature to

The Day of Atonement – One of a KindAlmost all biblical holidays relate to historical events and the natural cycle of the year. The Passover is a memorial to the departure from Egypt, the festival of Shavuot celebrates the full harvest (among other things), and Sukkot commemorates wandering of the Hebrews in the desert. On Purim and Hanukkah, we celebrate miraculous deliverance of the Jewish people. But not Yom Kippur. The holiday relates neither to events in nature nor a historical event. All other holidays, in addition to the spiritual symbolism and prophetic message, carry an atmosphere of joy and include a feast with delicious dishes. They are a time of thanksgiving and celebration. And again, this is not the case for the Day of Atonement. There are no banquets nor festivity.

What happens on Yom Kippur?The Day of Atonement points to the final judgment that is to come, following the return of the Messiah.The goal of fasting and abstaining from work is to focus solely on God and His grace. By denying one’s flesh, one learns to distinguish what is most important and what is secondary in life. We see clearer the difference between truth and fraud. Along with fasting and denying yourself any pleasures, most Jewish people wear plain white clothing with no jewelry, no leather nor any other elements symbolizing wealth or privilege. This act of humility could be interpreted as either imitating the garments of the priest or burial attire. Both analogies emphasize letting go of any excess. This Day of Reconciliation was and is very important to every Jewish believer, because it is a reminder that one day they will be reconciled with their God. The Lord of Hosts promised it will happen in just one day: “…I will remove the sin of this land in a single day.” Zechariah 3:9 And on top of that, on Yom Kippur God calls us to repent collectively. Repenting as One People on the Day of AtonementOur western world favors individualism. We speak of my church, my community, my calling, or my roles in life. While there is nothing wrong with this, it is the lens by which we read the Scriptures, often without realizing it. Yet, a beautiful aspect of traditional or biblical Jewish culture is the true sense of family. It is a shared responsibility and sense of togetherness. That is one of the treasured reminders in Yom Kippur. Several times in Leviticus 23, we read of this collective atonement. Verse 16 says that atonement was for the “uncleanness and rebellion of Israel, whatever their sins have been”. Verse 17 tells us that Aaron is making “atonement for him, his household and the whole community of Israel”. In verse 21, the priest was to “confess over it [the goat] all the wickedness and rebellion of the Israelites—all their sins…” Verse 34 says “Atonement is to be made once a year for all the sins of the Israelites.” Atonement for the Nation, not just an IndividualIt was clear that if you were a part of Israel, you shared the guilt and could not separate yourself individually. In Jewish culture, it was understood that if someone had sinned in some way, although you weren’t personally involved, you were still guilty. That is because you are a part of the community, and you let it happen on your watch. There was no picking and choosing. We are all responsible and all share a part. This community and togetherness theme is the language of much of the Scriptures and the church. Especially when it comes to sin and need for atonement. All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23). We are to bear one another’s burdens (Galatians 6:2). Love covers a multitude of sins (1 Peter 4:8). Sure, we can separate ourselves from messy situations or from family sin issues, even accurately insisting we are blameless. But what we are really doing is removing ourselves from our role in the community of believers.

The Weight of Yom KippurAs mentioned, the Day of Atonement is the most sacred day of the year in the biblical calendar. Even today in Israel, everything stops to remember the day. Major roads are blocked off and shut down. It allows families to walk and ride bikes down the middle of otherwise busy highways. On a personal level, some will try to make things right in a strained relationship, ask for forgiveness or extend it when necessary. It’s amazing to see a city or nation all but shut down with the intention of trying to extend or seek mercy for their wrongs. Even if much of it is inspired by tradition. It’s a unique and significant sight. Yom Kippur in the Bible Biblically, it was a little more serious. The consequences of working that day would permanently cut off the offender from Israel. It’s also the one day a year that God mandated a fast for everyone. Yet most importantly, on this day the high priest would enter the Holy of Holies to offer an atonement or a covering for the sins of Israel. In the TempleBack when the Jewish Temple still adorned the landscape of Jerusalem, Yom Kippur was the only day of the year when the High Priest could enter the Holy of Holies – the most holy place in the Temple. Two goats were brought before him and lots were cast, to determine which goat would become a sin offering for the people. Over the other goat the Priest was to confess all the wickedness of Israel, and the animal was to be driven out into the desert. It symbolized a release from sins for the entire nation (Leviticus 16). The priest was to enter behind the veil into the most holy place, and afterwards if we came out alive, it was a testimony that God accepted the sacrifice and forgave their sins. God said that this sacrifice mandate is eternal – God’s people were to honor it throughout the generations. But if there is no temple today, to offer sacrifices, how can one receive forgiveness of sins? Our AtonementLike the High Priest entered the holy place, Jesus went before God the Father to atone for our sins with His own blood (Hebrews 9:12). Instead of the goat, He was the One to shed His blood for us. Despite there being no Temple, He restored the meaning to the Day of Atonement. Jesus fulfilled the command of the Law by becoming the Yom Kippur sacrifice for all mankind. The day on which our Savior the Messiah was crucified became the day of redemption for all – the day of covering and forgiveness of sins (Zechariah 13:1). Our life and eternity depend on whether we know Him and have accepted Him as the one true Messiah. As the perfect sacrifice, Isaiah 53:12 says he “was numbered with the transgressors. For he bore the sins of many…” The only One who truly was blameless and didn’t need atonement or a sacrifice, He chose to be in this mess with us as if He did. If we are going to be like Him, how much more should we embrace our place with our brothers? The Perfect Sacrifice for Yom KippurRegardless of who did what, we need to be carrying each other’s burdens, walking together, forgiving, extending grace and fully receiving God’s atonement and perfect sacrifice. This is the message of Yom Kippur. Thankfully, Yeshua the Messiah made the perfect sacrifice once and for all. While this does ultimately fulfill the requirement for sin, God’s Yom Kippur instructions remain. Leviticus 23:31 “This is to be a lasting ordinance for the generations to come, wherever you live.” God’s intention was that forever we would have an annual reminder to stop and humble ourselves, address our shortcomings, and celebrate His complete atonement and sacrifice. We are still awaiting His second coming, when He will put an end to all sin and wipe off every tear. He will establish His eternal kingdom in Jerusalem. And Apostle Paul reminds us that on that day we will also be reconciled with the remnant of Israel:

|

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment