Roughly two thousand years ago, the Jewish sages of old (Chazal), with some help from the bible – e.g. Exodus 21:10 “… her food, her raiment, and her conjugal rights, shall he not diminish” – understood that love, although most potent of emotions, is not enough to ensure the future of the relationship between man and wife. They realized that existing Jewish matrimonial practices, many assimilated from other religions and cultures, were unjust according to Jewish thought. These led them to devise the Jewish marriage contract, the original pre-nuptial agreement, the “Ketubah” (plural “Ketubot”).

Written in Aramaic, the Ketubah was a revolutionary document at the time, aimed at securing the economic well-being of the wife and her children in case of an unexpected “departure” of the husband through dissolution of the marriage or the husband’s untimely death. This security is achieved by the groom making a monetary pledge of a sum sufficient to support his bride for a period of year after said departure. This commitment is made in front of two witnesses prior to the wedding ceremony, the only signatories to the Ketubah, and the bond is considered absolute, not allowing for any exceptions.

Although not a particularly long document, when we apply a magnifying glass to the Ketubah, we see that it is not “just a contract”, but rather many things that combine to make one of Judaism’s most important texts. The Ketubah is:

A binding contract

OK, only a moment ago we said that the Ketubah “is no just a contract”, but that’s because it is more. With that said, at it’s core it is very much a legal contract. In Israel, it is formally accepted as a legal agreement and in orthodox communities around the world, it is considered “sacred”. This view of the Ketubah as legally binding is a key reason for its creation in the first place and is the reason why it isn’t the newlyweds who sign the Ketubah, rather two adult male Jewish witnesses who must read it thoroughly before signing it.

A statement of the groom’s obligations to his bride

While the Ketubah itself puts much focus on the financial obligations of a husband in case of departure, a groom also obligates himself to qualitative commitments, such as committing to respect and cherish his wife, to provide for her, to have intimate relations, and more. In fact, the new husband promises not to leave the country without his wife’s approval.

Back to the financial side, the groom does make substantial commitments here as well, mostly that he will pay his wife a specified sum of money called “Mohar” upon ending of the marriage (in the case of death, this obligation carries through to the husband’s estate and inheritors). The sum of the mohar was originally 200 “Zuz” (an ancient coin from Talmudic times). Certain adjustments were made to the Ketubah over the ages to keep the sum to be paid relevant, and today, it is custom to set the amount at an 18th multiple (18 = Hai = life) of NIS / USD 1,000, e.g. NIS 18,000 or NIS 36,000, and to tie this sum to inflation (to the CPI).

A covenant of protection

In ancient times a woman, including all of her earnings, became the property of her husband upon matrimony*. As mentioned, the primary impetus for The Sages to institute the Ketubah was to ensure that a wife who exits her marriage is not left impoverished, forcing her to forgo her self-respect by needing to beg and making her a burden on the community. This, together with the other stipulations of the Ketubah, serve as protection on multiple plains:

- Economic protection, of course.

- Protection of a woman’s rights, to self-respect, to property and to be able to care for her children.

- Protection of a woman’s right to remarry – At the time, the Mohar monies were supposed to be sufficient for the former wife for an entire year, supposedly enough time for her to find a new spouse to care for her.

- Protection for the marriage and the marriage institute – In this case, the Ketubah and Mohar serve as deterrents to the groom from becoming unfaithful, reminding him not to act carelessly lest he be liable for the monies of the Mohar.

* Note: Owing to the truly ancient origins of the Ketubah, it is a one sided document, where a husband makes commitments to his wife, who, historically, was at a severe disadvantage. As such a document, the Ketubah contains certain notions which should be taken as they are, outdated. With that said, this is not sufficient for many Jewish couples, w

An integral part of the wedding ceremony

We began with mention of how the Ketubah is read in the middle of the wedding ceremony. We didn’t, however, mention that the timing of this reading, and of the Ketubah’s part in the wedding ceremony overall are also carefully planned:

Pre-wedding: Before the wedding even begins, the Ketubah is signed by two ketubah witnesses. Why? It’s simple – no Ketubah, no marriage! The importance of the Ketubah is such, that there is no reason to continue with the wedding without a signed Ketubah.

Mid-wedding: The Ketubah is read in front of the wedding guests at the point during the ceremony that separates between “Kiddushin” and “Nisuin”. Formally, the Jewish wedding is “a process” (yes, marriages are complicated too:) with two distinct stages:

- “Kiddushin”: Sanctification or dedication, also called “erusin”, meaning betrothal in Hebrew. In this section, the woman is prohibited from all other men, requiring a “get” (religious divorce) to dissolve the marriage.

- “Nissuin”: Marriage. From this point onward, the newlyweds begin their lives together, and cohabitation and procreation are permitted.

The Kiddushin focuses, although not completely, on the commitments of the bride to the groom. Therefore, it follows quite naturally that the Ketubah be read, outlining the groom’s commitments to the bride, before moving on to the Nissuin.

Post wedding:

At the end (or during) the wedding the Rabbi presiding over the ceremony hands the Ketubah to the wife for safekeeping. For the “mahmirim”, strictly observant Jews, cohabitation is only permitted if the wife has the Ketubah in her possession, and it if it is lost, the couple may only resume conjugal life after a replacement Ketubah has been procured.

Ancient Text and Tradition

The earliest known Ketubot were found in Egypt, dated around 440 B.C.E and in Maresha (near Beit Guvrin in Israel), dated around 176 B.C.E. The texts, written in Aramaic, are very similar. Minor changes have been made throughout the years, but the basics have stayed the same, and include (we refer here to the Ashkenazi version and discuss the very few differences in the Sephardic texts later on):

- A listing of particulars of the wedding event: the date and place of the wedding, the names of the bride and groom, and often of the parents.

- The aforementioned ”alimentation” clause, in which the groom promises the bride that he will “work for thee, honor, provide for, and support thee, in accordance with the practice of Jewish husbands”.

- A promise of Mohar, the sum the groom will pay the bride if the marriage is dissolved.

The earliest known Ketubot were found in Egypt, dated around 440 B.C.E and in Maresha (near Beit Guvrin in Israel), dated around 176 B.C.E. The texts, written in Aramaic, are very similar. Minor changes have been made throughout the years, but the basics have stayed the same, and include (we refer here to the Ashkenazi version and discuss the very few differences in the Sephardic texts later on):

- A listing of particulars of the wedding event: the date and place of the wedding, the names of the bride and groom, and often of the parents.

- The aforementioned ”alimentation” clause, in which the groom promises the bride that he will “work for thee, honor, provide for, and support thee, in accordance with the practice of Jewish husbands”.

- A promise of Mohar, the sum the groom will pay the bride if the marriage is dissolved.

- The establishment of a lien on the groom’s property, sufficient to ensure that he can meet the obligations of the Mohar, Nedunya (dowery) and Mattan (additional sum the groom will give to the bride, equal to the dowry). From a practical perspective, this makes the Ketubah a form of an insurance policy – the groom does not give the bride the monies listed here outright, as a gift, but promises to provide them in the case of divorce or upon the groom’s death.

- A testament to the act of “Kinyan”, the sealing the ketubah document. To make sure Ketubot were treated as authoritative legal documents which could mandate the transfer of property, the Sages required that there be an act of formal acquisition associated with the marriage contract. The Kinyan is a symbolic acquisition, usually signified by the groom’s acceptance, and subsequent return, of a token object such as a handkerchief, and it is conducted in front of the Ketubah witnesses before they sign it.

- Concluding clause which summarizes the terms described above.

- Names and signatures of the 2 witnesses, who, as mentioned, are other than the bride and groom.

A couple of related, interesting facts:

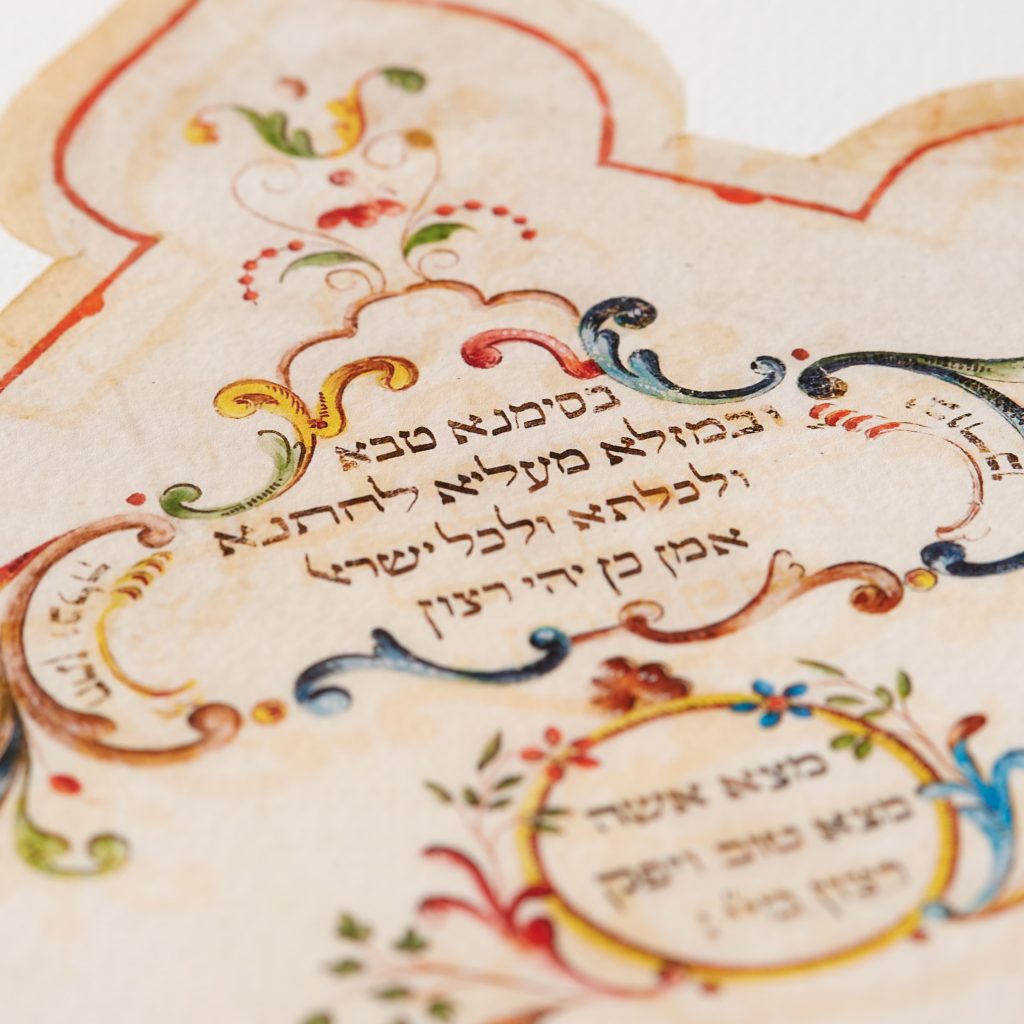

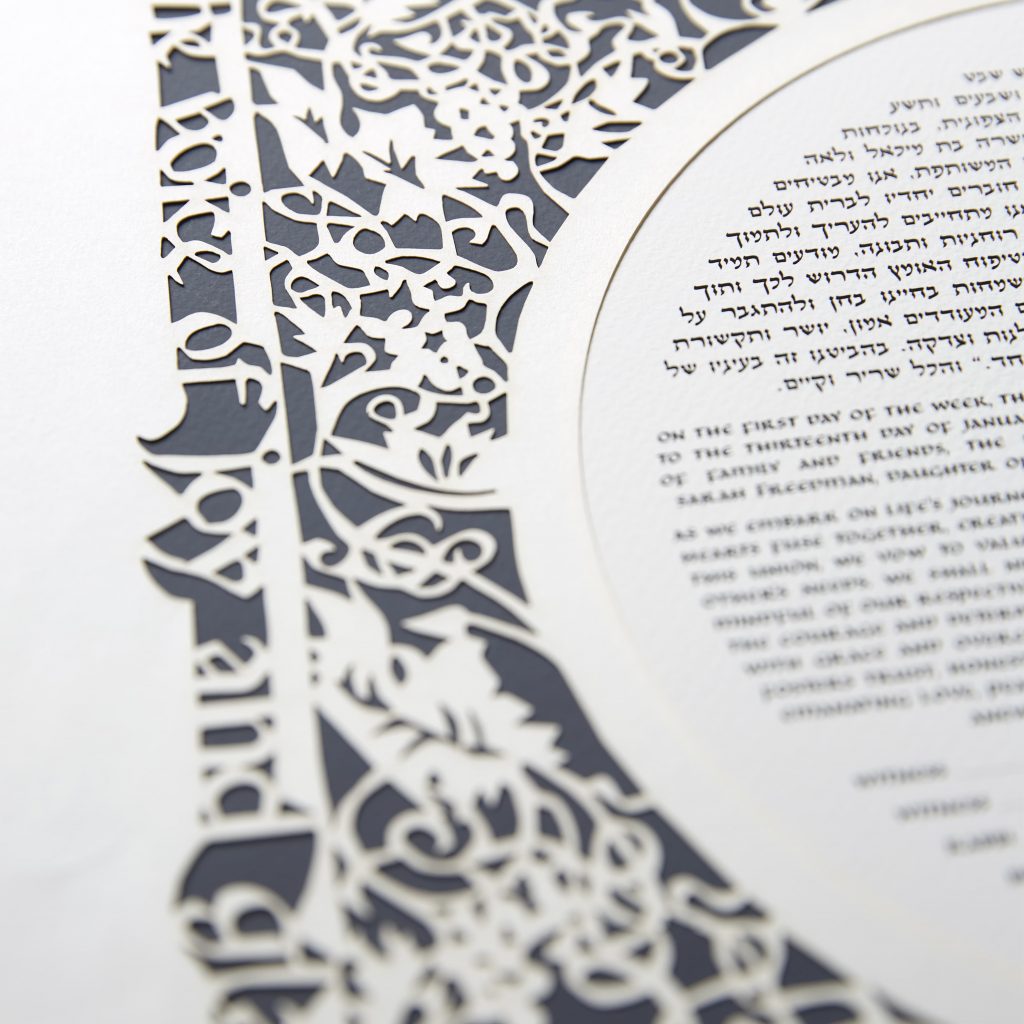

- The practice of creating decorative Ketubot is actually “required” by the Jewish custom of “Hiddur Mitzvah” (exaltation of mitzvahs). According to this tradition, objects used in the performance of religious obligations need to be appropriately adorned. The earliest known illuminated ketubah dates from the 10th century.

- In contrast to the Torah and other religious documents, a Ketubah, as a legal document, need not be written by a special scribe (Sofer) or written on parchment (Klaf).

The Sephardic Take on Ketubot

The similarities between the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Ketubot are much greater than the differences, however, these differences are definitely noteworthy, and you may wish to adopt them in your own Ketubah:

- Sephardic Ketubot often mention any significant neighboring geographic features, such as a nearby river or mountain.

- They may offer a brief description of the bride and groom in addition to giving their names.

- The bride, groom and their families choose how many generations to mention in the Ketubah. Typically, this is limited to two generations (parents and grandparents) but they may choose to list prior generations as well, especially if there is / was an influential Rabbi or Jewish leader in the family.

- The amount listed as the “bride’s value” is different for every Sephardic ketubah and is discussed and agreed upon by the couple and the Rabbi.

- At Sephardi weddings the ketubah is traditionally sung at the chuppah, not read.

- The exception to the prior fact, is the last part of the Ketubah, which discusses what would happen if the groom doesn’t abide by the Ketubah. It is definitely not sung, and many forgo reading it at all, to avoid “eyin harah” (the evil eye).

Summary

Over the years, many of our clients have told us that an understanding of the Ketubah has made not only their weddings more meaningful, but their marriages as well. We hope that this article has helped you connect more closely to this time honored tradition, and invite you to browse our wide selection of Ketubot, or, for additional information on Ketubot, please visit our “Ketubah Questions” section.

Elements of the ketubah can be traced back to Biblical times. During that period, when a man consented to his daughter’s engagement he was thereby facing the impending departure of a contributing member of his household and was viewed as requiring compensation for this loss. Thus, the groom’s family made a financial settlement, called a mohar, to the bride’s family as part of the engagement agreement. In addition, the groom would give wedding presents – mattan – to his bride.

In the post-Biblical era, as economic conditions changed, the financial obligations to compensate a bride and her family at the time of marriage proved onerous and made it difficult for young men without means to wed. Bride’s families began offering dowries to potential spouses in response. Moreover, the mohar was modified so that it was no longer a sum of money given directly to the bride’s father, but rather took the form of a mortgage or lien on the husband’s property, which he would be committed to paying out in the event of divorce, or which his estate would owe in the event of his death. The ketubah thus emerged as a way of documenting and certifying these arrangements, and ensuring that a woman had a legal record of them for her own security. The ketubah, in short, assured women of their rights and recourses in the face of the loss of their marriage.

The earliest extant ketubah dates from circa 440 B.C.E. found in Egypt and written on papyrus. This Aramaic document recorded the amount of the settlement the groom paid to the father of the bride and also noted the amount each family contributed to the dowry. The ketubah names the wife as beneficiary in the case of the husband’s death.

The ketubah text was first formalized about three hundred years later in the 1st century B.C.E. by the Sanhedrin (the presiding Judaic legislative body at the time); its authorship is attributed mainly to Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach. Despite undergoing several modifications since then, the ketubah text that has come down to us today closely resembles the one codified two thousand years ago. It is written in Aramaic, the language of legal and technical matters at the time, and an entire tractate of the Talmud is devoted to its intricacies

What Is Written In The Ketubah?

The ketubah’s multiple sections record the particulars of the wedding (date, names of bride and groom, etc.) and enumerate the groom’s obligations – financial and conjugal – to his bride.

Traditionally, the ketubah is not, as many people assume, a contract between husband and wife – neither, in fact, are required to sign the document. It is signed, rather, by two witnesses, who verify that the requisite conditions mentioned have been met by the groom. Another common misconception about the ketubah is that it in some way indicates that a man has purchased his wife, that it is some sort of transfer of property akin to a deed on a piece of land. This is not at all accurate – according to Jewish law there is no such relation of ownership between a husband and wife. The ketubah rather outlines the financial conditions that the groom must satisfy if the couple is to be permitted to undergo the wedding ceremony and become legally married

“The earliest extant ketubah dates from circa 440 B.C.E. found in Egypt and written on papyrus.”

What The Ketubah Is Today

Couples have continued to keep the tradition of a ketubah as an essential part of their Jewish wedding ceremony. Today, many artists and companies offer Ketubahs with texts that that speak to couples on a personal level in English. With the popularity of interfaith marriages and same sex weddings, couples can find ketubahs that fit their choices. Many Interfaith couples will include multiple languages such as Spanish or Chinese to include the other family. At times couples choose to write their own text which can include vows they are making to one another and poetry they love.

No comments:

Post a Comment